By Alan Buis,

NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

Few natural phenomena are as impressive or awesome to behold as glaciers and volcanoes. I’ve seen both with my own eyes. I’ve marveled at the enormous power of flowing ice as I trekked across a glacier on Washington’s Mount Rainier — an active, but dormant, volcano. And I’ve hiked a rugged lava field on Hawaii’s Big Island alone on a moonless night to witness the surreal majesty of a lava stream from Kilauea volcano spilling into the sea — its orange-red lava meeting the waves in billowing steam — while still more glowing ribbons of lava snaked down the mountain slopes behind me.

There are many places on Earth where fire meets ice. Volcanoes located in high-latitude regions are frequently snow- and ice-covered. In recent years, some have speculated that volcanic activity could be playing a role in the present-day loss of ice mass from Earth’s polar ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica. But does the science support that idea?

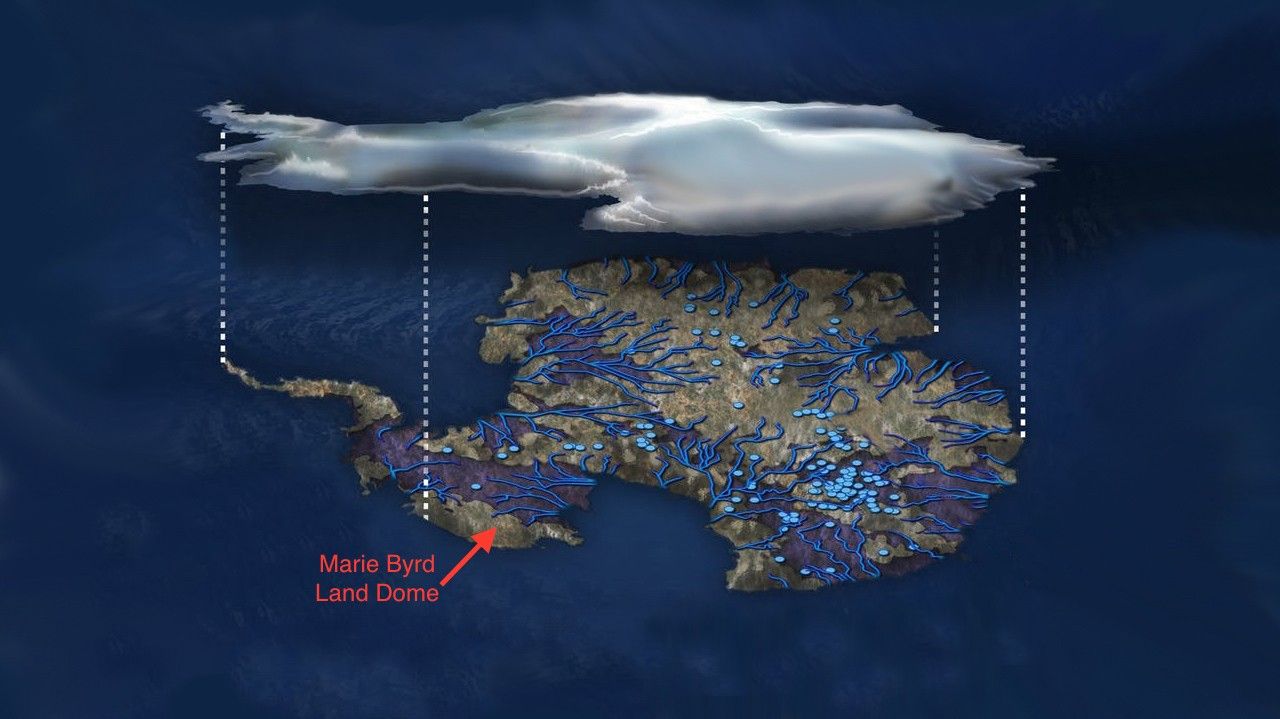

In short, the answer is a definitive “no,” though recent studies have shed important new light on the matter. For example, a 2017 NASA-led study by geophysicists Erik Ivins and Helene Seroussi of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory added evidence to bolster a longstanding hypothesis that a heat source called a mantle plume lies deep below Antarctica's Marie Byrd Land, explaining some of the melting that creates lakes and rivers under the ice sheet. While the study may help explain why the ice sheet collapsed rapidly in an earlier era of rapid climate change and why it’s so unstable today, the researchers emphasized that the heat source isn't a new or increasing threat to the West Antarctic ice sheet, but rather has been going on over geologic timescales, and therefore represents a background contribution to the melting of the ice sheet.

I checked in with Ivins and Seroussi to get a deeper understanding of this question, which our readers frequently ask about. Here's what I learned…

Greenland Has a Long-Departed “Hot Spot” but Is Now Quiet

Since 2002, the U.S./German Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) and GRACE Follow-On (GRACE-FO) satellite missions have recorded a rapid loss of ice mass from Greenland — at a rate of approximately 281 gigatonnes per year.

There’s plenty of evidence of volcanism in regions now covered by the Greenland ice sheet and the mountains around it, but this volcanic activity occurred in the distant past. Many of Greenland’s mountains are eroded flood basalts — high-volume lava eruptions that cover broad regions. Flood basalts are the biggest type of lava flows known on Earth.

But volcanic activity isn’t responsible for the current staggering loss of Greenland’s ice sheet, says Ivins. There are no active volcanoes in Greenland, nor are there any known mapped, dormant volcanoes under the Greenland ice sheet that were active during the Pliocene period of geological history that began more than 5.3 million years ago (volcanoes are considered active if they’ve erupted within the past 50,000 years). In fact, he says, the history of the Greenland ice sheet is probably more connected to atmospheric and ocean heat than it is to heat from the solid Earth. Ten million years ago, there was actually very little ice present in Greenland. The whole age of ice sheet waxing and waning in the Northern Hemisphere didn’t really get going until about five million years ago.

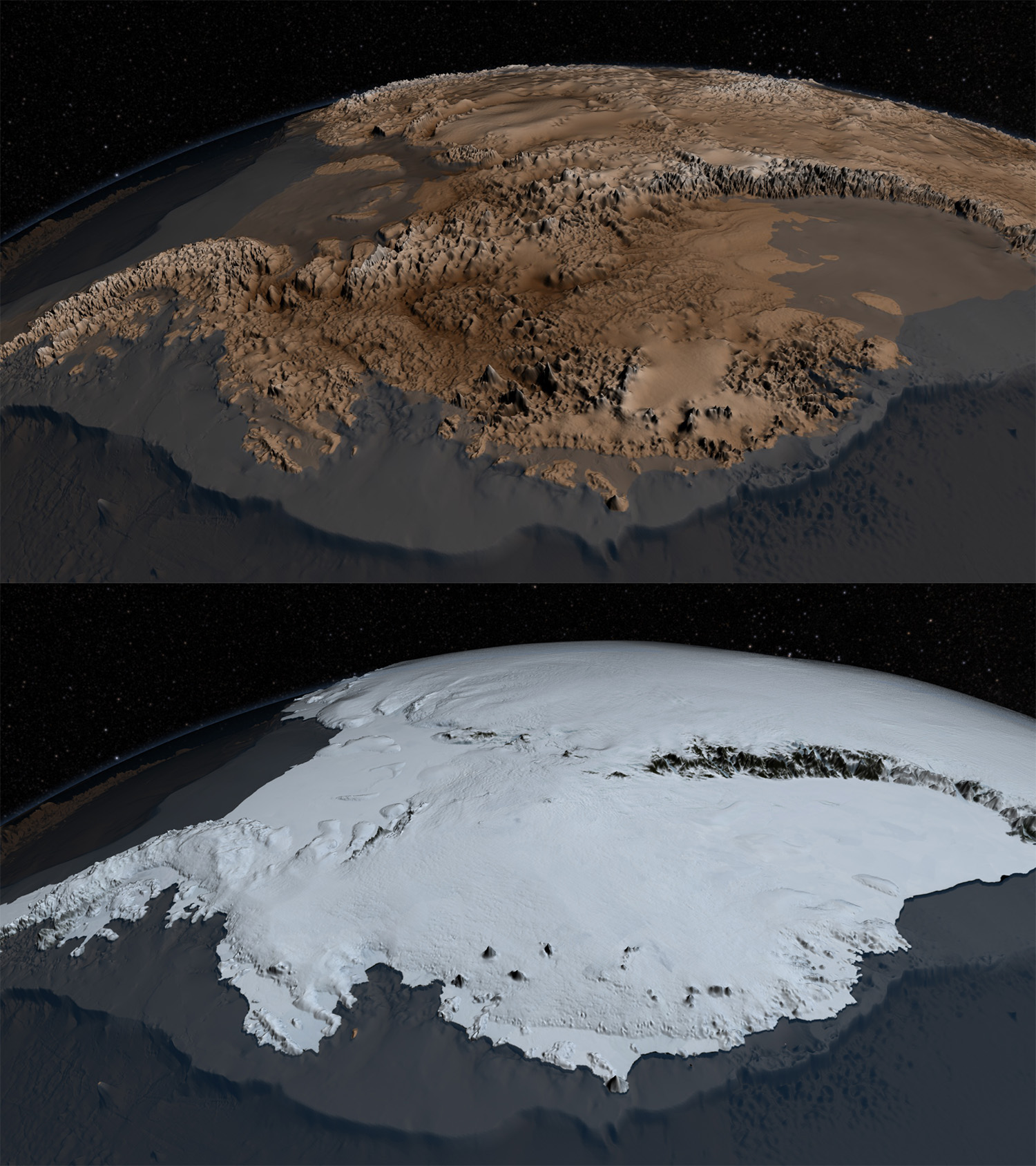

NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

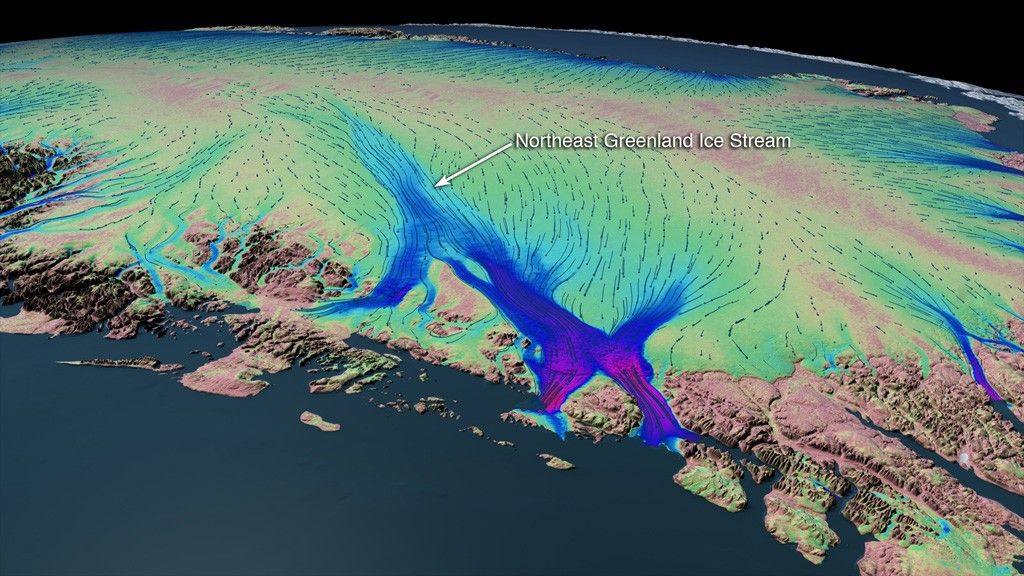

While there are no active volcanoes in Greenland, scientists are confident a “hot spot” — an area where heat from Earth’s mantle rises up to the surface as a thermal plume of buoyant rock — existed long ago beneath Greenland because they can see the residual heat in Earth’s crust, Ivins says. While mantle plumes can drive some forms of volcanoes, Ivins says they aren’t a factor in the current melting of the ice sheet. Researchers hypothesize however that this residual heat may drive the flow of the Northeast Greenland Ice Stream, which penetrates hundreds of kilometers inland (an ice stream is a faster-flowing current of ice within a larger and more stagnant ice sheet). Recent modeling experiments show that if enough residual heat is present, it can initiate an ice stream. GPS measurements also provide evidence that a hot spot once existed beneath Greenland.

That hot spot subsequently moved, however, and now lies beneath Iceland — home to about 130 volcanoes, of which roughly 30 are active. The hot spot is at least partially responsible for the island’s high volcanic activity. Iceland also lies along the tectonically active Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

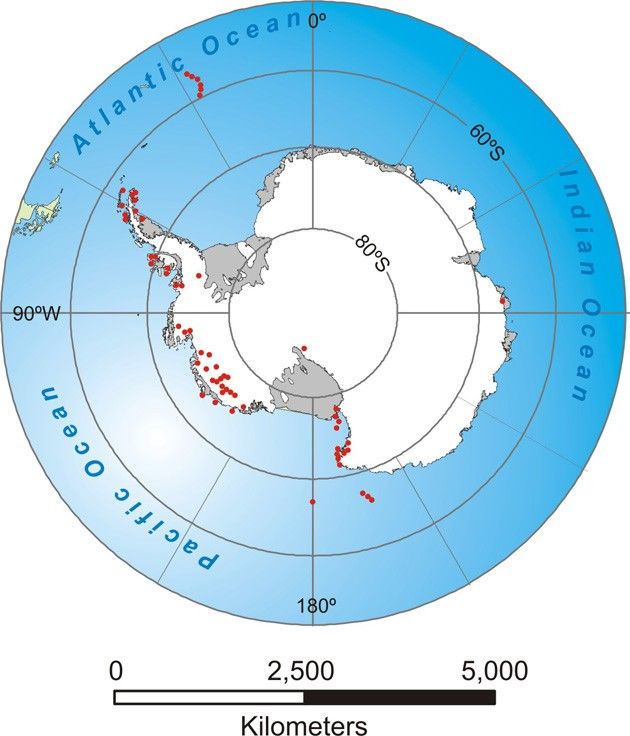

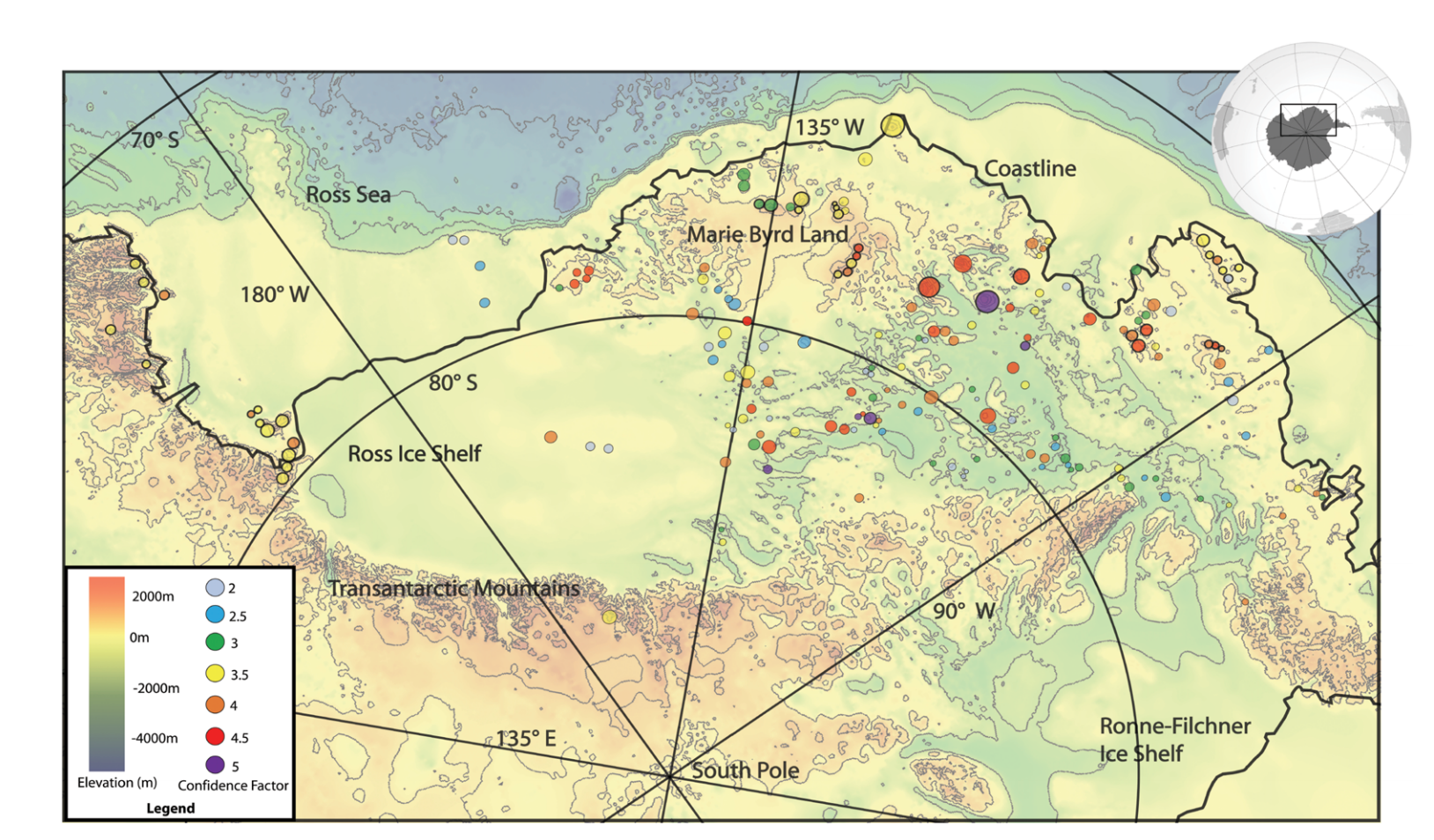

Antarctica Has Volcanoes, but There's No Link to its Current Ice Loss

The GRACE missions have also observed a rapid loss of ice mass in Antarctica, at a rate of approximately 146 gigatonnes per year since 2002. Unlike Greenland, however, there’s substantial evidence of volcanoes under the Antarctic Ice Sheet, some of which are currently active or have been in the recent geologic past. While the exact number of volcanoes in Antarctica is unknown, a recent study found 138 volcanoes in West Antarctica alone. Many of the active volcanoes are located in Marie Byrd Land. However, there’s no evidence of a dramatic volcanic eruption in Antarctica in the recent geologic past. Seroussi says details about the volcanism of many parts of Antarctica (particularly in East Antarctica) remain uncertain, both because they’re covered by ice and because their remoteness makes surveying them difficult.

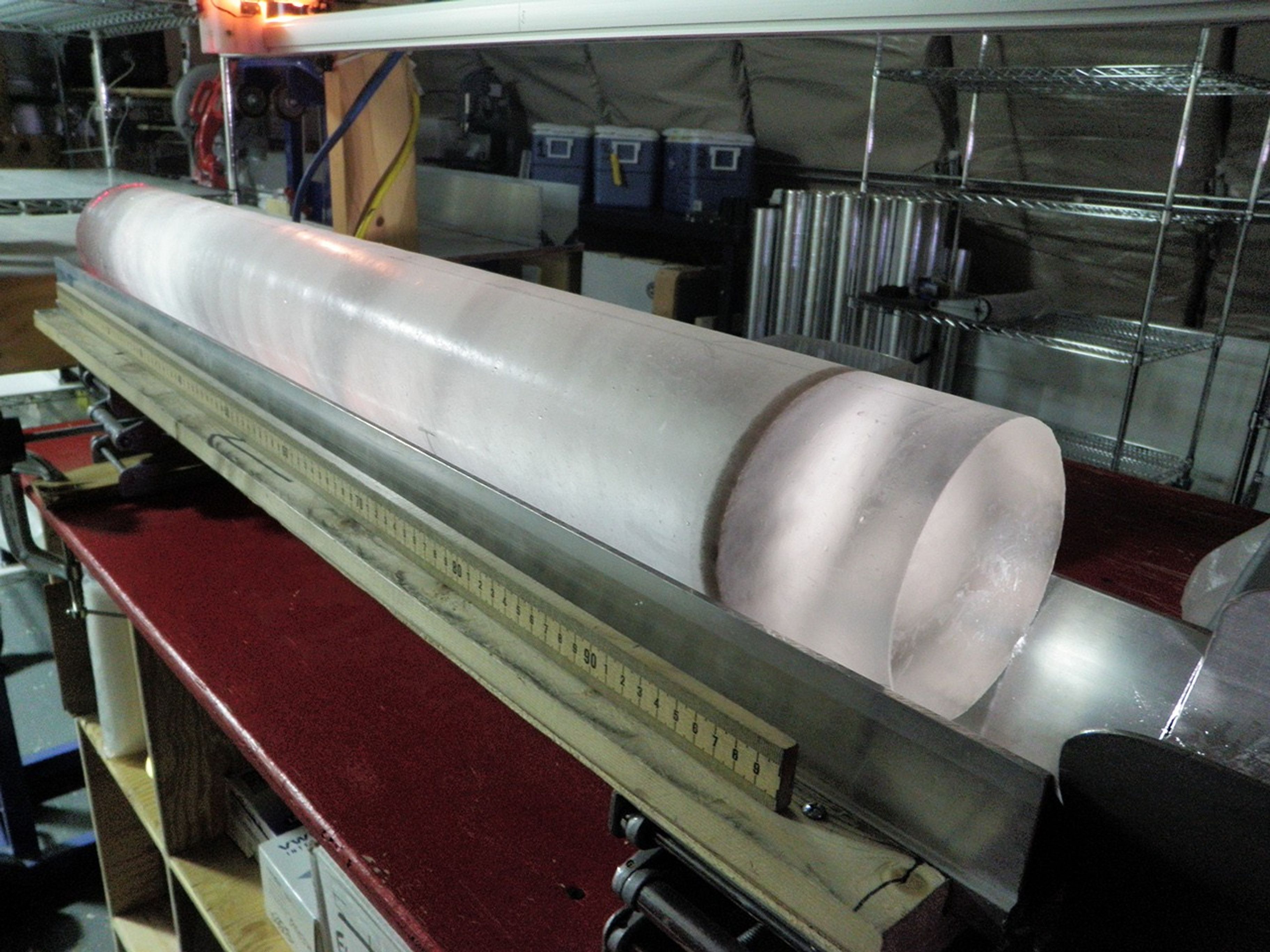

Multiple additional lines of evidence point to Antarctica’s past and present volcanism. For example, topographic maps of the bedrock beneath the Antarctic ice sheet give scientists clues to suspected volcanic locations. Analyses of volcanic rock samples reveal numerous volcanic eruptive events within the last 100,000 years, as do ash layers in ice cores. In their 2017 study of Marie Byrd Land, Seroussi and Ivins estimated the intensity of the heat produced by the hypothesized mantle plume by studying the meltwater produced under the ice sheet and its motion by measuring changes in the elevation of the ice surface.

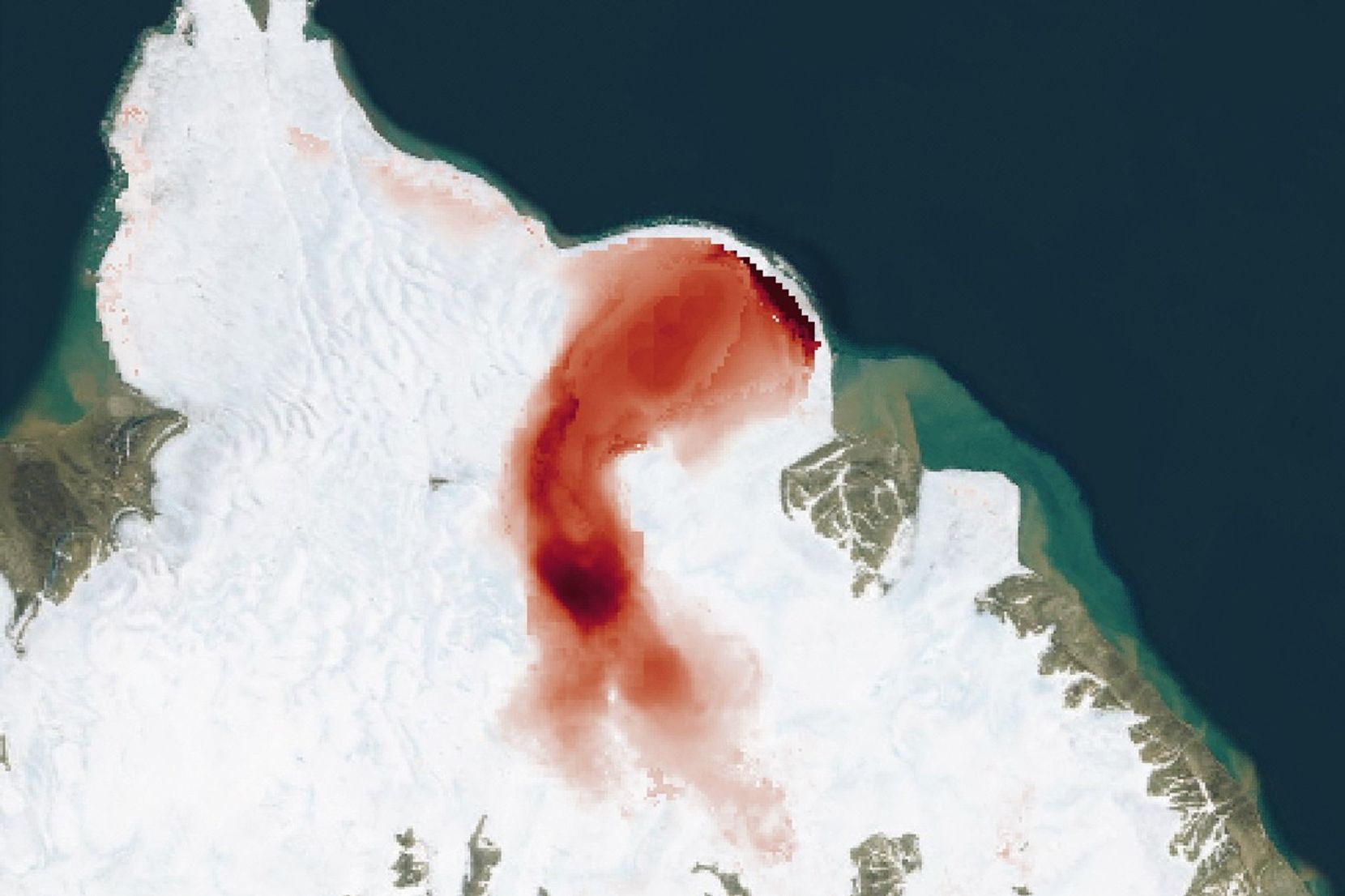

An intriguing paper by Loose et al. published in Nature Communications in 2018 provides additional evidence. The researchers measured the composition of isotopes of helium detected in glacial meltwater flowing from the Pine Island Glacier Ice Shelf. They found evidence of a source of volcanic heat upstream of the ice shelf. Located on the West Antarctic ice sheet, Pine Island Glacier is the fastest melting glacier in Antarctica, responsible for nearly a quarter of all Antarctic ice loss. By measuring the ratio between helium’s two naturally-occurring isotopes, scientists can tell whether the helium taps into Earth’s hot mantle or is a product of crust that is relatively passive tectonically.

The team found the helium originated in Earth’s mantle, pointing to a volcanic heat source that may be triggering melting beneath the glacier and feeding the water network beneath it. However, the researchers concluded that the volcanic heat is not a significant contributor to the glacial melt observed in the ocean in front of Pine Island Glacier Ice Shelf. Rather, they attributed the bulk of the melting to the warm temperature of the deep-water mass Pine Island Glacier flows into, which is melting the glacier from underneath.

Seroussi notes the changes happening now, especially in West Antarctica, are along the coast, which suggests the changes taking place in the ice sheet have nothing to do with volcanism, but are instead originating in the ocean. Ice streams reaching inland begin to flow and accelerate as ice along the coast disappears.

In addition, Seroussi says the tectonic plate that Antarctica rests upon is one of the most immobile on Earth. It’s surrounded by activity, but that activity also tends to keep it locked in position. There’s no reason to believe it would change today to impact the melting of the Antarctic ice sheet.

So, in conclusion, while Antarctica’s known volcanism does cause melting, Ivins and Seroussi agree there’s no connection between the loss of ice mass observed in Antarctica in recent decades and volcanic activity. The Antarctic ice sheet is at least 30 million years old, and volcanism there has been going on for millions of years. It's having no new effect on the current melting of the ice sheet.