By Alan Buis,

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory

In Brief

From insect-borne diseases to seasonal allergies and “superbugs,” climate change is quite literally getting under our skin, affecting our health in often surprising ways.

Second in a series on lesser-known impacts of climate change (see part 1).

If Earth came with a warning label, like the one the Surgeon General puts on cigarette packages, it might say something like:

“Warning: Climate change contributes to many well-known phenomena that negatively impact human health, including heat stress, extreme events, food insecurity, and poor air quality.”

Of course, not all the health impacts of climate change are as obvious or dramatic as those examples. Some are subtler, quite literally lurking under our skin. Here are a few.

Ticked Off

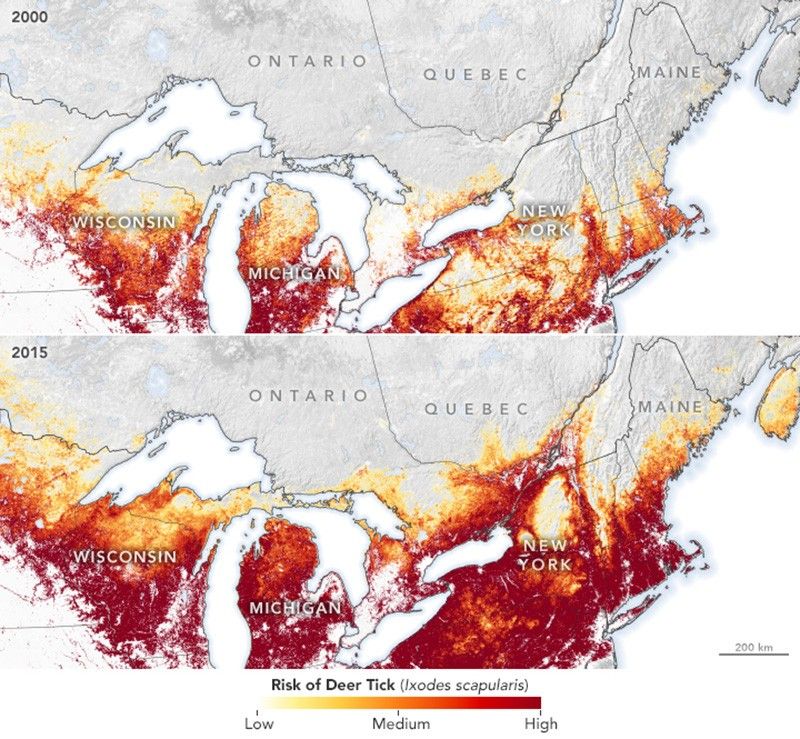

Cases of Lyme disease are on the rise in the United States and other parts of the world, and scientists believe climate change is a contributing factor. Lyme disease is a blood-borne illness transmitted by ticks to humans. It is found on all continents except Antarctica, but is most prevalent in parts of North America, Europe, and Asia. The disease causes headaches, fever, fatigue, and skin rashes. Untreated, it can affect the heart, joints, and central nervous system. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention officially reports about 30,000 cases of Lyme disease each year.

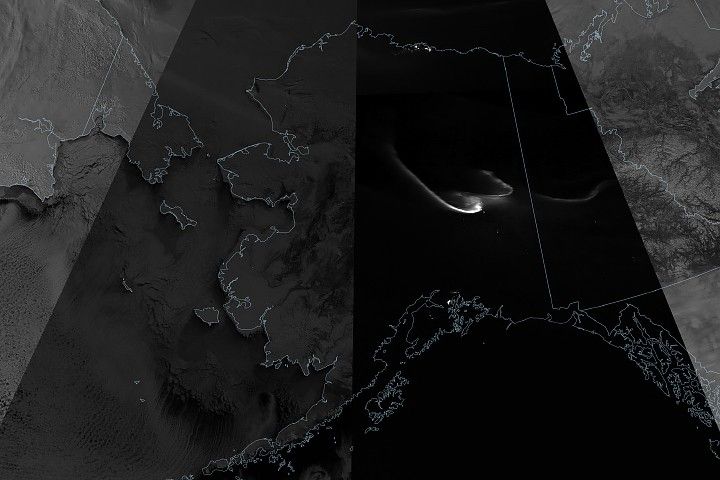

Researchers recently found that the risk of Lyme disease is expanding north in Canada. This is happening as global temperatures warm and areas become more habitable to ticks. The scientists combined NASA satellite data with field data of tick surveillance and weather station data to predict habitats suitable to deer ticks.

Previous research demonstrated how NASA/U.S. Geological Survey Landsat satellite data can help predict the risk of Lyme disease in high-exposure areas. Scientists at NASA’s Ames Research Center and New York Medical College combined Landsat imagery with geographic information system technology that helps manage, analyze, and visualize geographic data. They found residential areas covered by plants and trees and located adjacent to woodlands had a higher risk of Lyme disease transmission.

Mosquito Miseries

Mosquitoes can transmit deadly diseases to humans, like malaria, dengue, Zika, West Nile virus, and chikungunya. As climate warms, the reach of some mosquito-borne diseases is expanding.

A 2014 study in the journal Science found changing climate conditions are allowing mosquitoes to migrate to higher altitudes and latitudes. Climate-related droughts and extreme weather events are creating new mosquito breeding grounds. Warmer temperatures are also allowing mosquitoes to breed more quickly and for longer periods of time.

Scientists are using NASA satellite data to track vegetation health, rainfall, and temperatures and monitor environmental conditions favorable to mosquitoes. This allows them to predict where mosquitoes may breed and spread illness.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Joy Ng

As reported in 2017, NASA-funded researchers partnered with the Peruvian government to help forecast and prevent malaria outbreaks. They used the Land Data Assimilation System (LDAS), a land-surface modeling effort supported by NASA and other organizations that provides data and analysis on rain and snow, temperature, soil moisture, and vegetation. LDAS helped researchers identify where mosquito breeding grounds were likely to form.

Nothing to Sneeze At

Climate change appears to be making seasonal allergies worse.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 24 million Americans suffer from hay fever and about 10 million suffer from asthma. Each year, weeds, grasses, and trees release massive amounts of tiny pollen spores into the air to allow the plants to reproduce. That pollen gets into our eyes, ears, noses, and throats, which makes lots of us sneeze and itch, and can make breathing especially difficult for asthma sufferers.

Warmer temperatures and increased carbon dioxide levels are causing plants to bloom earlier and produce pollen longer each year. This is leading to more pollen in the air and a longer allergy season. A 2012 study found longer growing seasons may cause U.S. pollen levels to more than double by 2040.

A University of Maryland-led team investigated how changes in the timing of spring's arrival affected asthma hospitalizations. They used the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, derived from NASA satellite observations, to determine the arrival of spring by showing the relative “greenness” of vegetation. The early onset of spring (10 days early) was linked with a 17% increase in Maryland asthma hospitalizations from 2001 to 2012.

Zombie Superbugs

“Superbugs” are viruses and bacteria immune to antibiotics and antiviral medications. They’re a nightmare for microbiologists and doctors, but especially so for the patients infected with them.

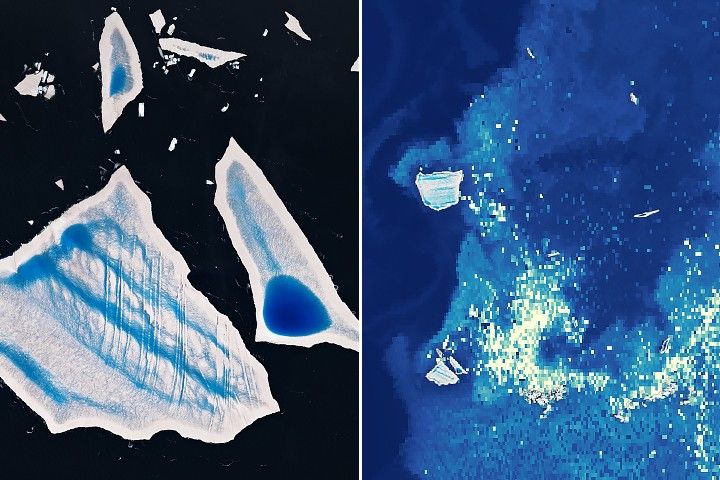

As our planet warms, scientists are concerned that the thawing of frozen Arctic soils (permafrost) may re-introduce diseases from ancient microorganisms that have been locked away in a frozen, dormant state for a million years or longer. A single gram of permafrost soil can contain thousands of microbial species. Some of these viruses, microbes, and bacteria could be resistant to antibiotics. Scientists worry antibiotic-resistant permafrost organisms could exchange genetic material with modern bacteria, creating superbugs.

Recent NASA-led research has cataloged these potential hazards. A study led by Kimberley Miner of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory examined the biological, chemical, and radioactive materials stored in ice, snow, and permafrost. The researchers noted that re-introducing ancient microorganisms back into the Arctic environment could disrupt ecosystems, kill wildlife, and put human health at risk.

Studies show about two-thirds of permafrost near the Arctic land surface may thaw by 2100. More than three million people live on permafrost in Earth’s high northern latitudes, and Arctic commerce, resource extraction, tourism, and populations are rising. This increases the risk humans may be exposed to emerging hazards and then transport them globally.