August 15, 2003

Above their heads, the afternoon sky is turning dark, even as fog drops like a curtain over the glacier-covered peaks of the mountains and fills the valley of the river flowing toward them. Olga Tutubalina and Sergey Chernomorets walk carefully along the left bank of the river through a mix of boulders, loose rocks, blocks of ice, and boot-sucking black mud that stretches for miles before disappearing into the fog and the folds of the mountains ahead. It’s their fourth trip to the Caucasus Mountains in the southern Russia republic of North Ossetia since October 2002. Today, they hope to finally see up close what so far they had only been able to see from a distance: the starting point of the largest glacial collapse ever recorded.

Avalanche

Running east to west across the narrow isthmus of land between the Caspian Sea to the east and the Black Sea to the west, the Caucasus Mountains make a physical barricade between southern Russia to the north and the countries of Georgia and Azerbaijan to the south. In their center, a series of 5,000-meter-plus summits (16,000-plus feet) stretch between two extinct volcanic giants: Mt. Elbrus at the western limit and Mt. Kazbek at the eastern. Volcanism fuels hot springs that steam in the alpine air. On the lower slopes, snow disappears in July and returns again in October. On the summit, winter is permanent. Glaciers cover peaks and steep-walled basins called cirques. The remote, sparsely populated area is popular with tourists and backpackers.

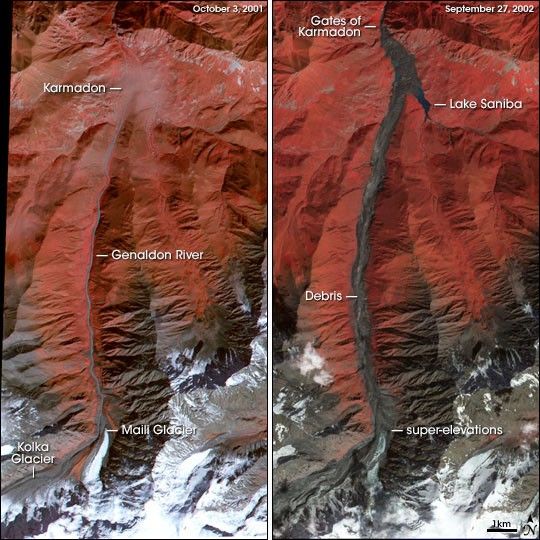

On the evening of September 20, 2002, in a cirque just west of Mt. Kazbek, chunks of rock and hanging glacier on the north face of Mt. Dzhimarai-Khokh tumbled onto the Kolka glacier below. Kolka shattered, setting off a massive avalanche of ice, snow, and rocks that poured into the Genaldon River valley. Hurtling downriver nearly 8 miles, the avalanche exploded into the Karmadon Depression, a small bowl of land between two mountain ridges, and swallowed the village of Nizhniy Karmadon and several other settlements.

At the northern end of the depression, the churning mass of debris reached a choke point: the Gates of Karmadon, the narrow entrance to a steep-walled gorge. Gigantic blocks of ice and rock jammed into the narrow slot, and water and mud sluiced through. Trapped by the blockage, avalanche debris crashed like waves against the mountains and then finally cemented into a towering dam of dirty ice and rock. At least 125 people were lost beneath the ice.

Dmitry Petrakov, Sergey Chernomorets, and Olga Tutubalina have been returning to the site since the disaster. The three have been friends and colleagues for several years. Tutubalina and Petrakov are members of the Faculty of Geography at Moscow State University. She teaches and researches in the Laboratory of Aerospace Methods for the Department of Cartography and Geoinformatics, and he is a researcher in the Department of Cryolithology and Glaciology. Chernomorets is the General Director of the University Centre for Engineering Geodynamics and Monitoring in Moscow.

The combination of backgrounds made the team uniquely qualified to study the Kolka disaster. In the year following the event, they made five trips to the Russian Republic of Ossetia in the central Caucasus. They wanted to figure out exactly what had happened that day and to forecast what might happen in coming weeks, months, and years at the site.

A Dangerous Past

After the collapse, people speculated that something called a glacial surge had triggered the Kolka collapse. “In a surge,” explained Petrakov, “the leading edge of a glacier might slip a few hundred meters down slope very rapidly—perhaps in a day. A similar event happened at Kolka in 1969.” In 1902, a more significant collapse at Kolka Glacier had killed 32 people. Despite a history of disasters there, routine monitoring of the Kolka Glacier cirque ended shortly before the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

It was the region’s dangerous past that drew Chernomorets, Petrakov, and Tutubalina to the area in September 2001, the year before the catastrophe. The three had enjoyed a camping trip to the region to see the site of the 1902 collapse, explore the glaciers, and enjoy the scenery. In the absence of regular scientific monitoring of the Kolka Glacier, the group’s observations during that trip were some of the most recent.

“We arrived in Karmadon in the evening of September 21. It was getting dark, and we could barely see the valley slopes,” Tutubalina says. “We remember discussing: ‘Well, although hill-walking rules do not recommend camping near mountain rivers, the sky is clear, and at the end of September, debris flows from the slopes are unlikely, so we should be all right.’” They camped right by the Genaldon River. The same decision a year later would have cost them their lives.

Getting to Kolka

In the days following the disaster, survivors were demoralized and afraid of what might happen next. Petrakov, Chernomorets, and Tutubalina felt they had to help calm people’s fears if they could, or help them prepare for any further disaster if they could not. “The disaster happened on Friday night, about 8 p.m., and the news of it didn’t reach Moscow until the next morning,” recalls Tutubalina. “Sergey and I were taking a stroll in a national park some 50 kilometers west of Moscow, when Dmitry rang Sergey’s mobile [phone], and told us the news he’d just seen on the Internet. We wanted to fly to the area with the rapid response team of the Russian Emercom [Russian Emergencies Ministry] because we had specialist knowledge to assess the situation. When we got back to Moscow in the evening, Sergey started calling the Emercom people, but by the time we got in touch, it was too late to join the plane.”

They spent the next 10 days following the situation through mass media and Emercom reports, while struggling to find funding for their own expedition. When promised funding fell through again and again, they gave up and used their own money.

“This was a unique event of a planetary scale,” Tutubalina explains. “We felt we could make a significant contribution to the study of the scale of the disaster and the remaining danger, as we knew what the area looked like one year earlier.” Because the glacier had not been routinely monitored in more than a decade, the team’s 2001 sightseeing observations were some of the most recent.

The decision to fund the trip out of their pockets ruled out any helicopter support to transport heavy scientific equipment. They could only take equipment they could fit and carry in their backpacks along with their camping gear and food. They stuffed their packs with GPS units for mapping the precise location of important geologic and glaciological reference points, simple geodetic equipment for measuring angles and topography, and digital and photographic cameras. Thanks to colleagues from the Caucasus region—Eduard Zaporozchenko and Alexander Polkvoy—they were able to reach Karmadon despite the fact that local transport had stopped after the disaster.

First Impressions

Petrakov and Chernomorets reached the site for the first time in the first week of October, two weeks after the disaster. Tutubalina was teaching and had to stay behind. What they saw stunned and saddened them. “It was terrifying,” says Petrakov. “There was this mass of black ice—a wall—blocking the Karmadon Gorge. On the surface of the ice, lakes were filling up. We had seen the pictures on the TV, and so, in one way, we were prepared. But when we arrived it was very foggy and overcast, which made it appear much more dangerous, and, well…,” he pauses while he searches for the word, “sad.”

“The scale was so great that it really was hard to imagine how it could have happened,” adds Chernomorets. “I have been studying there [the Caucasus] for many years, seen many debris flows and avalanches in this region, but nothing to compare to that.” By the time they arrived at the site, there was no hope there would be survivors. Only 20 bodies were ever found.

“It was very dangerous at that time,” says Chernomorets. “We were trying to walk up the Genaldon, and constantly you had to watch where you stepped because the path was muddy and full of rocks that moved all the time. But you also had to look up because the walls of the valley were lined with blocks of ice and falling rock.”

The Safety of Satellites

Mapping the temporary lakes and watching them for signs of sudden and catastrophic release became a top priority. Chernomorets and his colleagues Ivan and Inna Krylenko helped collect topographic survey data to map the coastlines and conducted echo soundings to measure the depth of the largest one, called Lake Saniba.

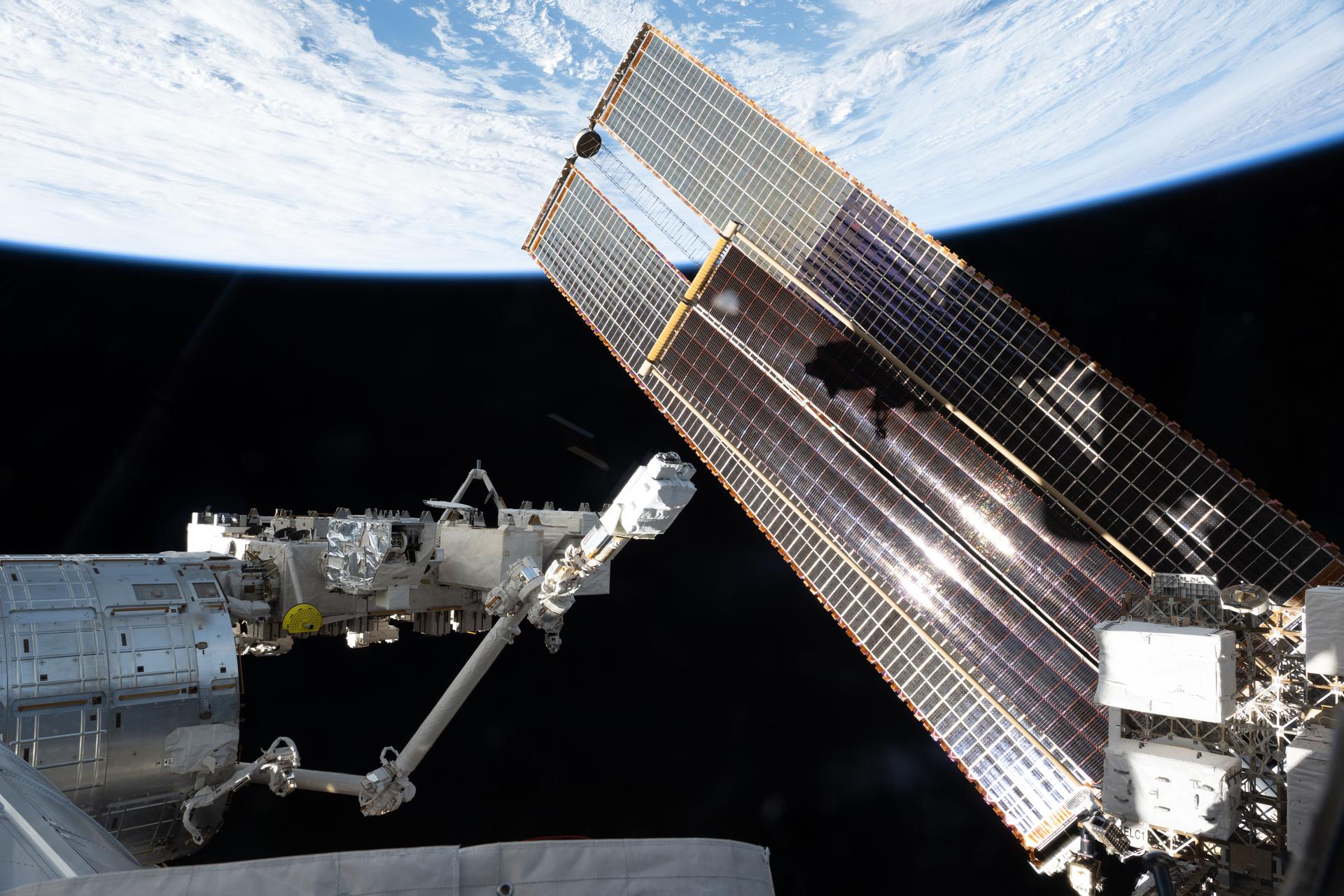

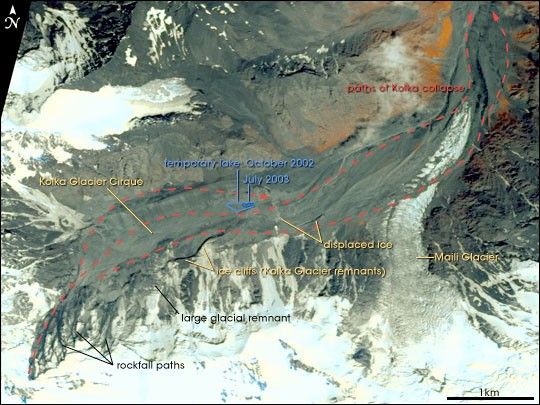

“In the October 2002 trip,” Chernomorets says, “we did not yet have any satellite observations. But after we returned we received remote sensing imagery from a number of sources—photos from the astronauts on the International Space Station showing the pre- and post-disaster landscape and ASTER [Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer] data from NASA’s Terra satellite for pre- and post-disaster comparisons. Eventually we also acquired imagery from the Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellite, the American commercial satellite Quickbird, and the Advanced Land Imager on NASA’s Earth Observing-1 satellite.”

Throughout the remainder of 2002 and into the late spring of 2003, frequent fogs and dangerous weather conditions prevented on-site visits or aerial photography of the glaciers, so the IRS satellite data that were collected periodically by Research and Development Center ScanEx in Moscow became the key method for monitoring the glaciers and lakes. The three scientists were relieved to observe the lakes began to disappear one by one, likely draining through channels and crevasses appearing in the ice mass. By summer 2003, only three of the original 13 remained.

“The satellite imagery enabled us to assess the extent of the disaster, map the boundaries of specific areas, and compile sketch maps of the whole area,” says Tutubalina. The scientists also put the satellite images to a practical use. When the danger of spring snow avalanches cleared, and they were able to return to the site in June 2003, they discovered that in the scoured and ice-covered landscape, the recent satellite images made better route maps than any pre-disaster topographic map.

Exploring the Origin

August 15, 2003

Above the rushing sound of the river on their right, they hear the broken staccato of rock falling on rock and the thundering train sound of debris flows sliding down mountains. The rain starts to pour down. They walk silently, watching the rock-littered ground at their feet, the unstable slopes, the darkening sky. As they pick their way up the valley toward the Kolka Glacier, they hear the sound of thunder and know they have to decide. Ahead is the Kolka, unexplored. Behind them is the safety of base camp and the possibility that for the fourth time, they will go back to Moscow without seeing Kolka.

Rockfalls and debris flows begin to pour down both sides of the valley toward them; the river swells into a thundering, muddy canal. Unwilling to turn back, Tutubalina, Chernomorets, and three other team members head upstream as fast as people with heavy backpacks can move through a pathless maze of mud, ice, and rocks. They set up an intermediate camp away from the river near the hot springs at the headwaters of the Genaldon River. They soak in the hot springs, watching the rain die down, and knowing they were lucky to have found a safe route between the violent river and the crumbling slopes.

“From the beginning we knew the most interesting thing scientifically was the site of the collapse, the top of the glacier, but on our first visits, it was so blocked by debris and ice that we hadn’t been able to get to it yet,” Chernomorets recalls. Some people were still attributing the event to a glacier surge, and others were blaming it on unusually high snowfall that season. The volume of the temporary lakes and the flooding that accompanied the avalanche suggested a hidden reservoir of water in the glacier. Many scientists had come to the conclusion that volcanic and tectonic processes were responsible. To decide which explanations were most likely, they needed to investigate the site where the disaster originated: the Kolka Glacier and Mt. Dzhimarai-Khokh.

In the early morning after their scare in the thunderstorm, Tutubalina, Chernomorets, and their team awoke early. “You must arrive at the base of the glacier early in the day to cross the Kolka stream,” explains Tutubalina, “because the Sun comes up and melts the ice, and the stream grows and cannot be crossed.” They arrived at the base of the Kolka Glacier while the stream could still be crossed. After months of waiting, they were finally there.

Watching their feet as they walked among the ice and rocks in the moraines below the glacier, they saw something none of them had ever seen before: numerous rows of parallel scratches gouged into the rocks. These striations, as glaciologists call the scratches, are usually only seen on the bedrock underlying a glacier. They are made over years or decades as the glacier creeps down a slope and etches the rock beneath.

Petrakov emphasizes how unusual this is. “Glaciers have cycles of advance and retreat. When the glacier retreats, ice-embedded rocks at the edge of the glacier are exposed. When the glacier advances again, the rocks are just pushed along in front. Moraine rocks are not scraped by the glacier because they move with it. But at Kolka, the collapse happened so fast that the ice mass must have simply flown over the moraine, producing striations several millimeters deep in minutes.” The depth and direction of the striations created a snapshot of the avalanche as it passed through, and the scientists used their observations to reconstruct and map the first stages of the avalanche.

Almost a year after the disaster, the slopes of the scoured cirque and the exposed face of Mount Dzhimarai-Khokh were still unstable. Seven separate couloirs (ravines) on the north face of the mountain were still actively collapsing, with continuous rock falls, ice and snow avalanches, and debris flows every fifteen minutes. “That kind of activity is unheard of, especially so long after the initial event,” says Petrakov. Glaciers that once crept down slopes and fed the Kolka now ended in precarious-looking ice walls. A particularly unstable-looking one that was dissected by gigantic parallel crevasses was being bombarded with rockfalls from above, triggering ice avalanches that spilled onto the bottom of the cirque.

Fast and Furious

Among all the unusual findings, however, the most shocking things about the event were the most simple—the immense volume of debris and how fast it moved. Using an image-analysis computer program, the scientists compared the results of a laser-ranging topographic survey of the ice and debris backed up behind the Gates of Karmadon to pre-disaster topographic maps of the region. They estimate that the avalanche deposited between 105 and 125 million cubic meters of ice and rock in the Genaldon Valley upriver from the Gates of Karmadon. An additional 20 million cubic meters of material were deposited in various parts of the valley. If it had had the room to spread out,that much material could have covered all of Washington, D.C., (176 square kilometers, or 68 square miles) with a layer of ice and debris more than 2 feet thick. Confined within the slopes of the Genaldon River valley, the block of ice reached heights of 130 meters (about 390 feet) at the entrance to the Karmadon Gorge and stretched back upriver for miles.

Several clues pointed to enormous speeds. Normally avalanches and debris flows will follow the bottom of a river valley. In the Genaldon, however, the velocity of the avalanche was so great that in places the debris climbed the walls, creating pushed-up piles of debris called “super-elevations.” The Kolka Glacier basin makes almost a right angle where it turns north into the Genaldon valley. Rushing too fast to make the turn, the avalanche left a super-elevation 150 meters (almost 500 feet) high on the eastern slope of the valley. When the mass arrived at the Gates of Karmadon and could not pass through the narrow opening to the gorge, it crashed like a wave against the mountains and left large super-elevations high above the valley floor.

A more chilling estimate of the flow’s velocity was provided by seismic recorders and a power plant clock. “The seismic recorders on five seismic stations in North Ossetia recorded the first vibration of what was probably the collapse of the hanging glacier from Dzhimarai-Khokh onto Kolka,” says Tutubalina. “Five and half minutes later, according to a clock at a nearby power station, the main line into Karmadon was destroyed.” If those clocks were reasonably in sync, the avalanche would have been traveling at 180 kilometers per hour (112 mph) when it hit the power line. Eyewitnesses describe hearing the thunderous roar of the avalanche and seeing sparks in the night sky.

Dormant but Dangerous

There are more than a dozen other scientists studying the event, and, so far, no one—including Petrakov, Chernomorets, and Tutubalina—is sure what the root cause of the catastrophe was. “To the east and a little south of Kolka is the Kazbek volcano,” says Chernomorets. Volcanism of the dormant Kazbek is responsible for the area’s popular hot springs. “There was a lot of water associated with this event, and we don’t think all of it could have come from the heating caused by friction as the ice mass moved. So one of the questions about this collapse is where did all the water come from?”

There is uncertainty also about what triggered the collapse of rocks and hanging glaciers on Mount Dzhimarai-Khokh. Two small earthquakes jarred the region in the months before the collapse, and probably destabilized the hanging glaciers. There is another interesting factor to consider: in the first days after the collapse, an Emercom crew flew to the site via helicopter, but was forced to evacuate immediately when the crew detected an overpowering smell of sulfur-containing gas. It seems there may be some fumaroles—volcanic vents—on the face of Mount Dzhimarai-Khokh in the area where the hanging glacier collapsed. As for excessive snowfall, says the team, “It was insignificant compared to the total amount of material moved in the event. If the snowfall played any role, we believe it was secondary to volcanic and tectonic influences.”

The future of Kolka and the Karmadon Ice Mass

In a paper that has been recently published in the Russian Journal Kriosfera Zemli, Petrakov, Tutubalina, and Chernomorets present their findings from the previous year in the form of maps and annotated satellite images of the catastrophe area. The maps include the extent of the ice mass and debris fields, the location of temporary lakes and flooded and buried settlements, and the former and current extent of the glaciers in the Kolka cirque.

Based on the available data and observations, the scientists say they don’t expect any additional catastrophic processes within the next 10 to 20 years. The remaining lakes will likely continue to drain through crevasses and channels being cut through the ice mass, and as they drain, the risk of flooding decreases. “The rivers are eroding the ice mass faster than we previously anticipated,” says Tutubalina. “The ice mass will have largely melted in 2-3 years, we think, but may take up to 10 years to completely disappear.” Some of the slope glaciers that are being bombarded with rock falls from Mt. Dzhimarai-Khokh may eventually collapse into the basin of the Kolka cirque, but there is so little of the Kolka Glacier remaining below, that such a collapse isn’t likely to trigger any catastrophic avalanches.

Meanwhile, grass has started colonizing the super elevations and softening the raw, scoured look of the slopes. “The whole area is changing so fast that we are rapidly losing evidence that would increase our understanding of the processes involved in the collapse. We must speed up our observations of the area before too much valuable information is lost,” says Chernomorets.

For example, on the August 2003 expedition, the scientists were guided by a recent high-resolution image from the IRS sensor. “On the image, we could see some unusual textures that were not typical for glaciers in the area,” noted Tutubalina. Some of these textures turned out to be piles of porous, granulated ice lining the sides and bottom of the remains of the Kolka Glacier. This material is not typical glacier ice, which shows distinct, compressed layers that reflect centuries of yearly snowfall. Chernomorets thinks an expert on ice and snow crystals should examine the material to see if they contain clues about the forces involved in the collapse.

There is no shortage of ideas for further studies. They want a vertical sounding survey of the new thickness of the Kolka Glacier. They also want to work with geologists to map tectonic fault lines in the Kolka Cirque; the ongoing rock falls and debris flows make them wonder about tectonic instability. And of course, they want to have someone collect air samples at the suspected fumaroles. “We have to remember that in addition to the 1902 event at Kolka, there are historical accounts of glacier collapses on the southern and eastern slopes of Kazbek in the past few centuries,” says Chernomorets. Dormant, but still dangerous, the volcano could be the key to them all.

Links

- Mount Kazbek, Caucasus, Russia

- Space Shuttle View after Kolka Glacier Collapse

- Russian Kolka Glacier Collapses

- Rapid ASTER Imaging Facilitates Timely Assessment of Glacier Hazards and Disasters

NASA Earth Observatory story by Rebecca Lindsey. Design by Robert Simmon.