Mertz Loses Part of Its Tongue

-

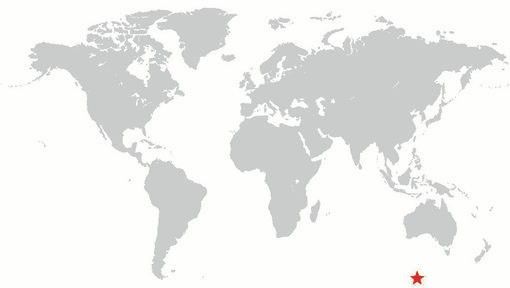

Antarctica

The Mertz Glacier flows off East Antarctica and forms a long, narrow tongue pointing in the direction of Australia and New Zealand. That tongue routinely calves icebergs into the Southern Ocean, and the Earth Observing-1 satellite spotted it doing just that in January 2010.

Deep cracks, or crevasses, give the glacier tongue a rough and rugged texture, which carried over to this rippled iceberg. Such ice is often swept up by ocean currents circling Antarctica, and icebergs can remain relatively intact for months or years, so long as they remain in sufficiently cool conditions. Some icebergs, however, drift northward to warmer climates and disintegrate. By observing the response of an iceberg to warmer conditions, scientists can make predictions about how ice shelves—thick slabs of ice attached to coastlines—might respond to a warming climate.

Swimming with Ice Cubes

-

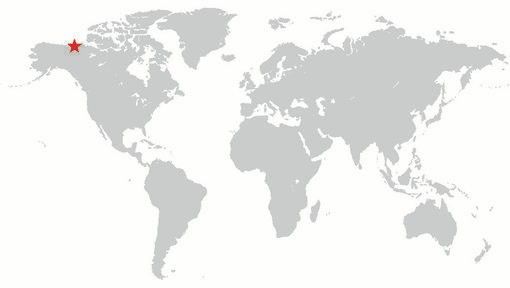

United States

The ice season on the Great Lakes was longer in 2013–14 than anything in the satellite records to date or in anyone’s memory. For nearly seven months, ice was afloat somewhere on the Great Lakes. In an average year, the lakes are ice-free by late April or early May—even as air temperatures onshore approached 27° Celsius (80° Fahrenheit) on some days. In 2014, the last ice melted in mid-June.

On May 23, 2014—the start of Memorial Day weekend (and unofficial start of summer in the United States)—Landsat 8 captured this image of ice in Lake Superior near Chequamegon Bay, Wisconsin. Satellite imagery of ice is one of many tools that government agencies use to manage shipping on the Great Lakes.

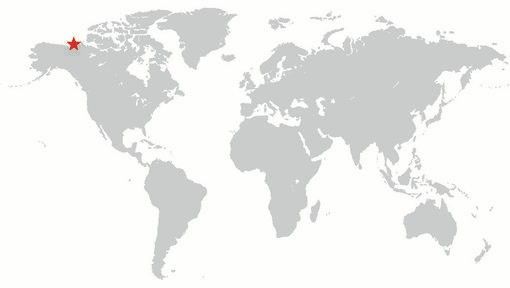

Franz Josef Land

-

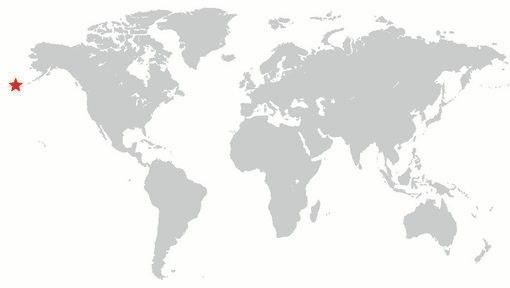

Arctic Ocean

Located just 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) from the North Pole, Franz Josef Land is perpetually coated with ice. Glaciers cover roughly 85 percent of the archipelago’s land mass, and sea ice floats in the channels between islands even in the summertime. The Terra satellite observed some of the islands in visible and near-infrared light in August 2011.

The amount of sea ice filling the channels between the islands of Franz Josef Land varies from summer to summer. Most of the ice in this scene is anchored to land, as large glaciers blanket the islands. Yet today’s glaciers are tiny compared to the ice sheet that dominated the region about 20,000 years ago. Raised beaches, which preserve evidence of land rising as the crushing weight of overlying glaciers eases (known as isostatic rebound), were first recognized on the islands in the late 19th century.

No Green in This Land

-

Greenland

Ranging in color from snow white to turquoise, sea ice lined the shoreline of eastern Greenland in June 2000 when Landsat 7 acquired this image. Snowcaps form dendritic patterns on the brown landscape, leaving south-facing slopes especially bare.

On the eastern promontory, “fast ice” clings to the shoreline. Common over shallow ocean waters along shorelines, fast ice holds fast to the shore or sea bottom, not moving with winds or currents. Off the coast, pieces of bright white sea ice float on the sea surface at the whim of the elements.

Some of the fast ice in this image is blue, likely because it is composed of large crystals that were stretched by the relentless, transformative action of wind.

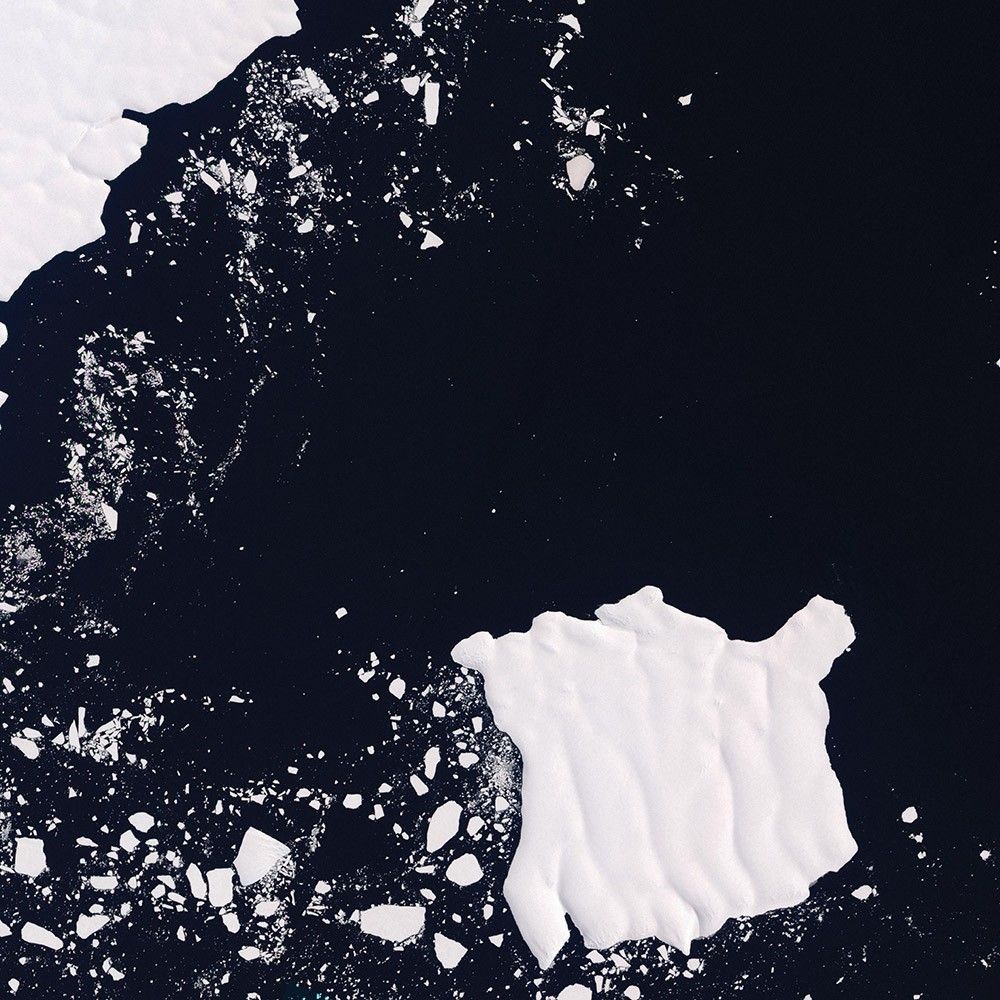

Mackenzie Meets Beaufort

-

Canada

The intersection of Canada’s Mackenzie River and the Beaufort Sea is beautiful, and it is also important to the health of the Arctic ice cap. Research has shown that fresh water flowing from rivers into the Arctic Ocean can have a significant effect on the extent of sea ice cover. Warm-water discharges can accelerate the melting of sea ice near the coast. It also can create more open water, which is darker than ice and absorbs more heat from sunlight.

In the image, tan and brown water masses show up on both sides of the sea ice that crowds the shoreline of the river delta. A massive pulse of warm river water—colored by sediments and organic material flowing out from the Canadian interior—flows right under the ice. The pulse raised offshore water temperatures across hundreds of kilometers and seemed to contribute to the melting and dispersal of nearby sea ice.

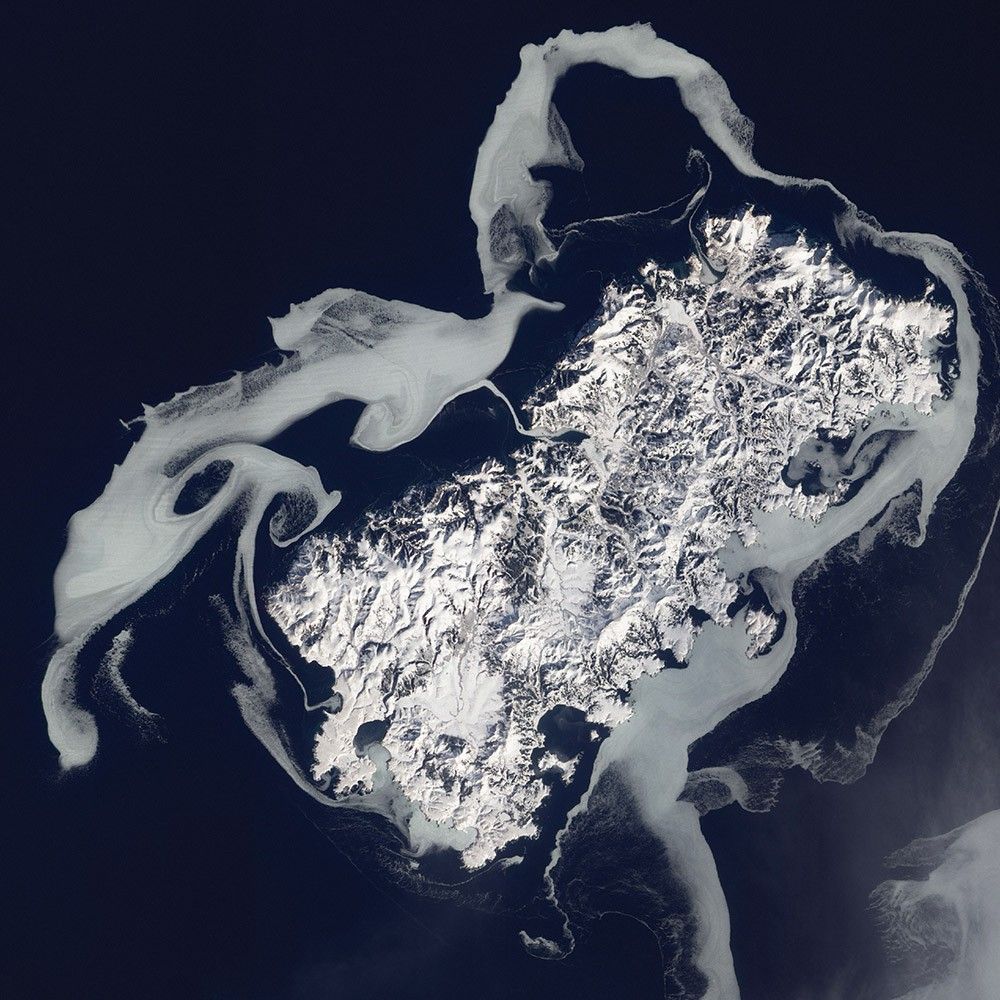

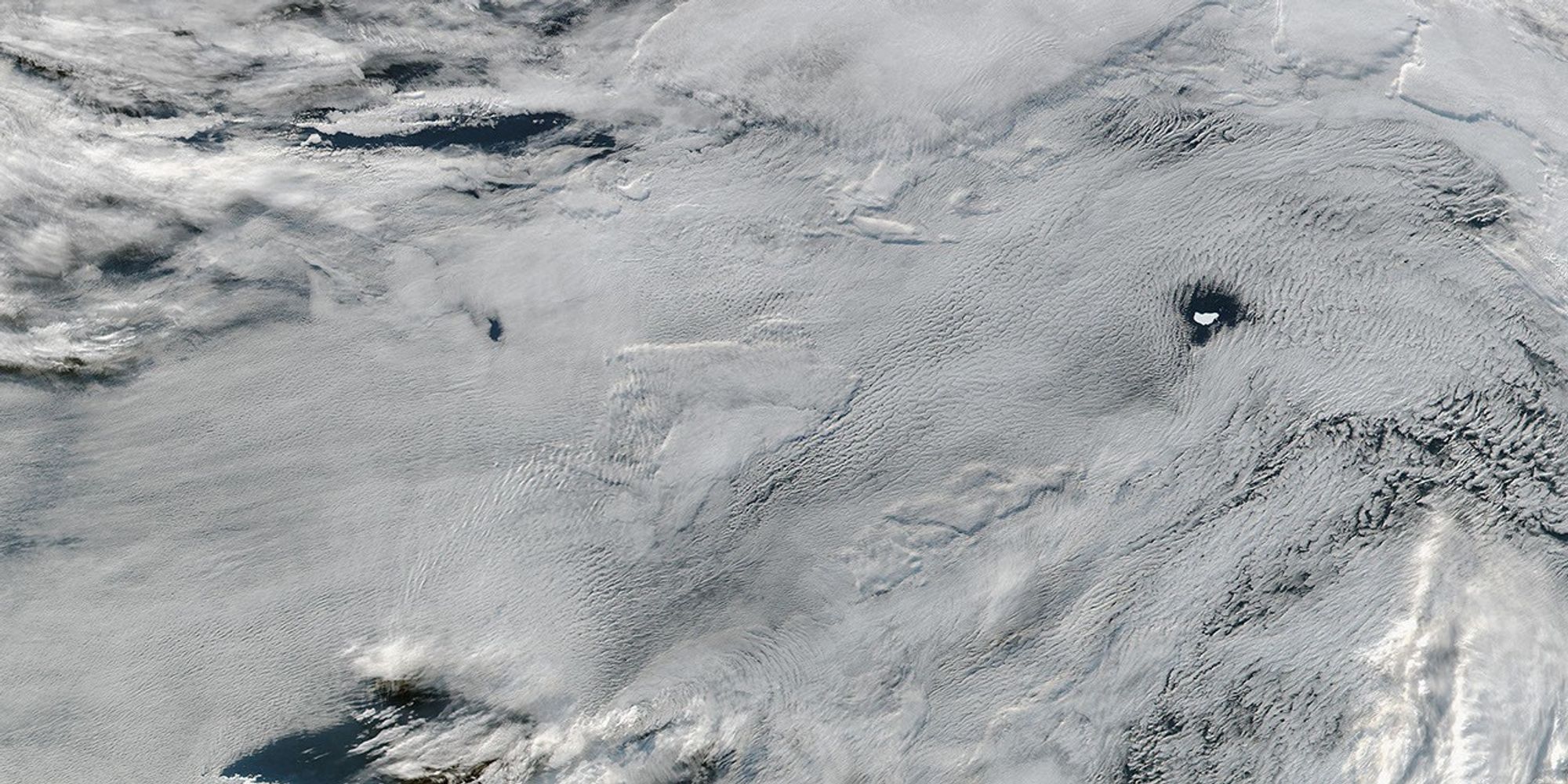

Sea Ice at Shikotan

-

Japan and Russia

Ostrov Shikotan is a volcanic island at the southern end of the Kuril chain. At about 43 degrees north—more than halfway to the Equator—Shikotan lies along the extreme southern edge of winter sea ice in the Northern Hemisphere. The Earth Observing-1 satellite captured this image of swirling blue-gray sea ice around Shikotan in February 2011.

The ice here tends to move with currents and eddies, which has shaped it into rough circles. The eddies may result from opposing winds from the north and southwest.

Uneven snow cover exaggerates the island’s rugged appearance. Multiple forces have shaped Shikotan over millions of years. It has been battered by tsunamis—although wind, rain, and tectonic forces likely play a greater role in shaping the surface.

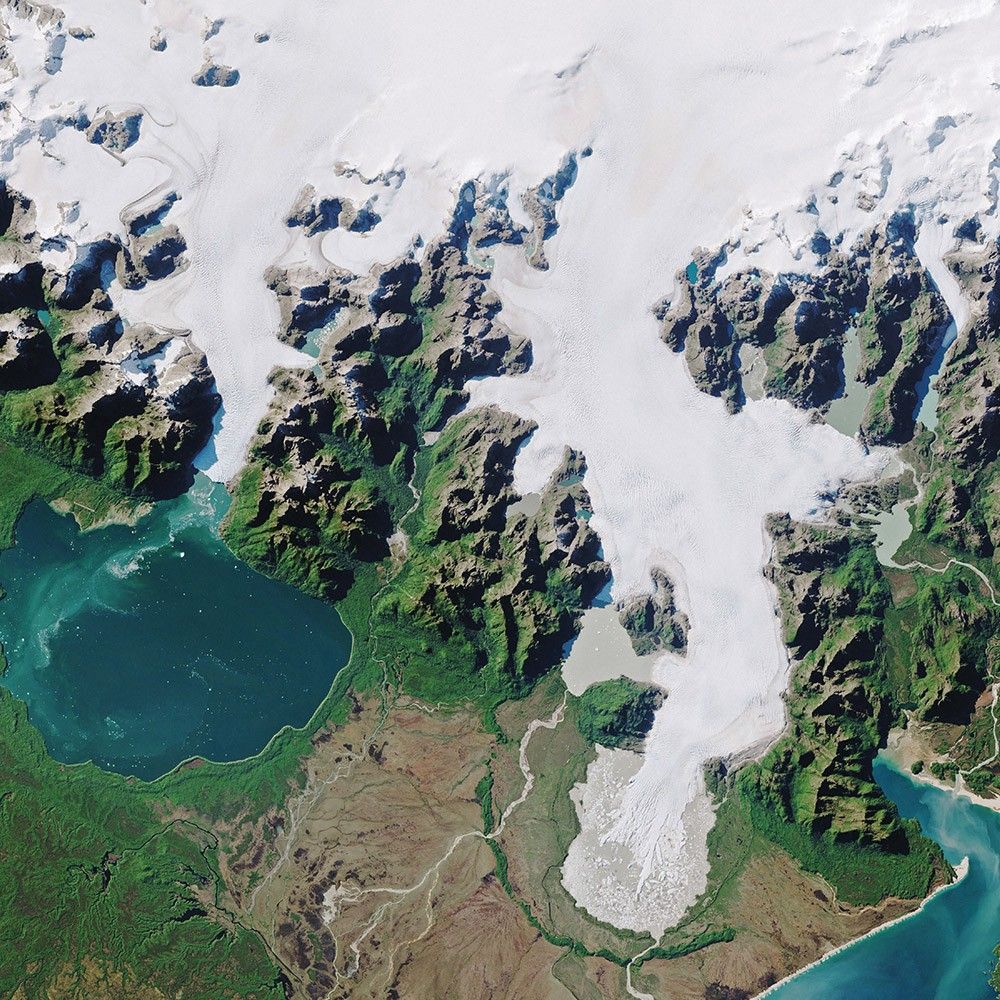

North Patagonian Icefield

-

South America

Forests, grasslands, deserts, and mountains are all part of the Patagonian landscape that spans more than a million square kilometers of South America. Toward the western side, expanses of dense, compacted ice stretch for hundreds of kilometers of the Andes mountain range in Chile and Argentina. The two lobes of the Patagonian icefields—north and south—are what is left of a much more expansive ice sheet that reached its maximum size about 18,000 years ago. The modern icefields are just a fraction of their previous size, though they remain the southern hemisphere’s largest expanse of ice outside of Antarctica.

The northern icefield covers about 4,000 square kilometers and has 30 significant glaciers along its perimeter. In April 2017, Landsat 8 captured this rare cloud-free view of a portion of the icefield.

Ice creeps downslope through mountain valleys and exits through so-called “outlet glaciers.” Many come to an abrupt end on land, while others terminate in water. The San Rafael and San Quintín glaciers (shown at the right) are the icefield’s largest. Both have been receding rapidly in the past 30 years.

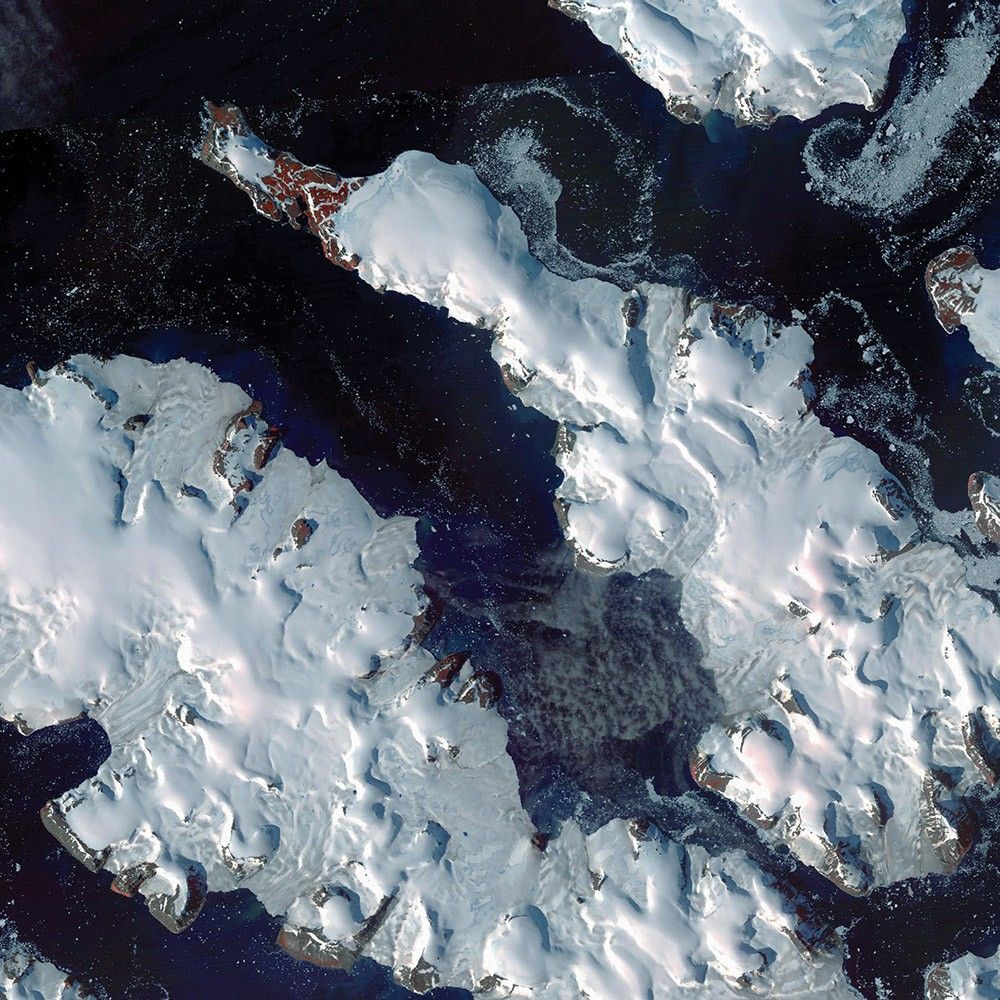

Manning Island and Foxe Basin

-

Canada

Although it may look like a microscope’s view of a thin slice of mineral-speckled rock, this image was actually acquired in space by the Earth Observing-1 satellite in July 2012. It shows a small set of islands and a rich mixture of ice in Foxe Basin, the shallow northern reaches of Hudson Bay.

The small and diverse sizes of the ice floes indicate that they were melting. The darkest colors in the image are open water. Snow-free ice appears gray, while snow-covered ice appears white. The small, dark features on many of the floes are likely melt ponds.

Foxe Basin sea ice is known for having an unusual brown color due to staining from sediment from rivers. Also, the basin is shallow enough that it is often rich with marine sediments kicked up from the bay floor. The Manning Islands stand to the lower left, beneath the bright white wedge.

Ice Water

-

United States

As temperatures rise in the summer, turquoise splotches of color begin to speckle the icy surfaces of the Arctic. Those splashes of blue are melt ponds—areas where snow has melted and pooled in low spots atop glaciers and sea ice. During an airborne research campaign in July 2014, a scientist shot this photograph while flying over a glacier in southeastern Alaska. Chunks of ice float on the pond’s turquoise water.

Many questions remain about the impact of melt ponds on the Arctic. Compared to bright white snow and ice, liquid water absorbs much more heat from sunlight. So when a pool of water forms on top of ice, it changes the heat balance. The water warms in the sunlight and can speed the melting of surrounding ice, influencing the overall melting and movement of ice sheets and sea ice.

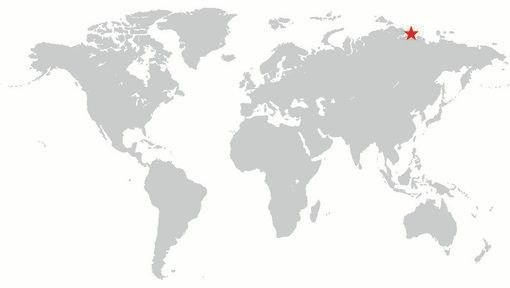

Omulyakhskaya and Khromskaya

-

Russia

Along the northern Siberian coast, near Omulyakhskaya and Khromskaya Bays, the landscape is dotted with lakes. Known as thermokarst lakes, these pools are made from the thawing of frozen soil, or permafrost, and the accumulation of that melt water in low spots in the terrain.

Although far too cold for a swim, the water is generally warm compared to the surrounding soil, so it can slowly thaw more permafrost and make the lake deepen and expand over time. Occasionally the basins merge or even drain into streams and the bay. Dark brown spots in the image are probably locations of former thermokarst lakes.

Because thawing permafrost and thermokarst lakes release carbon and methane—both greenhouse gases—scientists monitor these landscapes closely because of their implications for future climate.

Phytoplankton on Ice

-

Antarctica

It may look like someone dyed the water, but the green hue visible off the coast of Antarctica is entirely natural. Granite Harbor, a cove near Antarctica’s Ross Sea, got its color from phytoplankton at the water’s surface. These microscopic, plant-like organisms typically flourish here in spring and summer, when the edge of the sea ice recedes and there is ample sunlight. But scientists have noticed that, given the right conditions, they can grow in autumn, too. In March 2017, Landsat 8 captured such an event in this image.

Sea ice, winds, sunlight, nutrient availability, and predators all factor into whether plankton can grow in large enough quantities to color the slush-ice and make it visible from space. Phytoplankton are important for the ecology of the Southern Ocean, as they are an abundant food source for zooplankton, fish, and other marine species.

Heart-Shaped Uummannaq

-

Greenland

It is no mystery how Uummannaq Island got its name. In Greenlandic, the word means “heart-shaped,” an apt description for the multi-peaked mountain that towers over the island.

Located off the coast of northwestern Greenland, the mountain’s granite and gneiss peak rises sharply from sea level to about 1,170 meters (3,840 feet). The rock that makes up Uummannaq is ancient, likely forming 3.0 to 2.8 billion years ago.

Well north of the Arctic Circle, Uummannaq Island is home to one of the most northerly towns in Greenland. The Earth Observing-1 satellite captured this image in May 2012. Sea ice still surrounded the island, but breaks in the ice—called leads—exposed seawater beneath it.

Puma Yumco

-

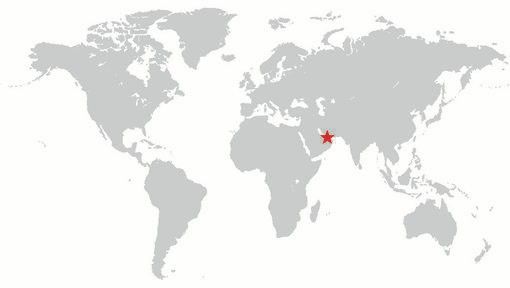

China

Several hundred lakes dot the expansive Tibetan Plateau. With the average elevation exceeding 4,500 meters (14,800 feet) above sea level, these lakes are among the highest in the world.

Recent research suggests that the number and surface area of lakes on the Tibetan Plateau has increased significantly since the 1990s.

Puma Yumco is one of the larger lakes in southern Tibet. Tuiwa, a small village along the eastern edge of the lake, is reportedly one of the highest settlements in the world. Every winter, Tuiwa villagers herd thousands of sheep across the lake’s frozen surface to two small islands, where the soil is more fertile and the forage is better.

Grounded in the Caspian

-

Kazakhstan

A wide variety of ice forms in the Caspian Sea, which stretches from Kazakhstan to Iran. Just offshore, a well-developed expanse of consolidated ice appears bright white. Farther offshore, a gray-white field of chunky, hummocked ice has detached and is slowly drifting around a polynya, an area of open water surrounded by sea ice. That darker patch is actually growing young, thin ice and nilas, a term that designates sea ice crust up to 10 centimeters (4 inches) in thickness.

The close-up shows nilas and a white, diamond-shaped piece of ice. It might look like this chunk is on the move, cutting a path through thinner ice. But it’s more likely that the “diamond” was stuck to the sea bottom and the wind pushed ice around it.

Ice-Covered Delta

-

Canada

In the Mackenzie River Delta of far northern Canada, snow- and ice-covered waterways stand out amid green, pine-covered land. Those frozen tributaries also become ice roads for trucks carrying supplies between the remote outposts of Inuvik and Tuktoyaktuk.

The Mackenzie River system is Canada’s largest watershed, and the 10th largest water basin in the world. The river runs 4,200 kilometers (2,600 miles) from the Columbia Icefield in the Canadian Rockies to the Arctic Ocean.

Every so often, flooding from the Mackenzie River replenishes the surrounding lakes and ponds, some of which sit atop permafrost. This landscape is home to caribou, waterfowl, and a number of fish species. Also, thousands of reindeer travel through this area each year on the way to their calving grounds.