A Curious Ensemble of Wonderful Features

-

United States

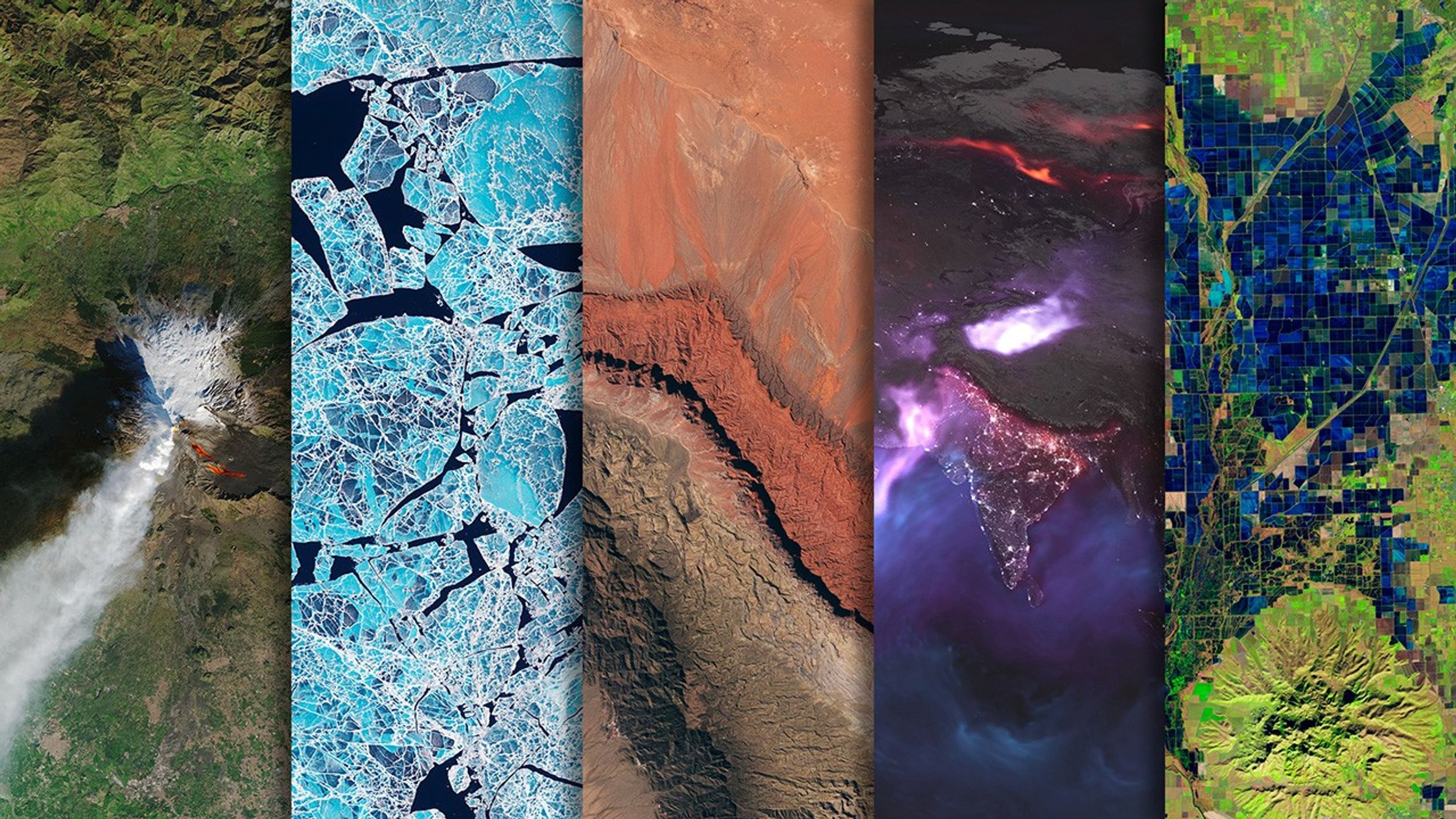

When John Wesley Powell led an expedition down the Colorado River and through the Grand Canyon in 1869, he was confronted with a daunting landscape. At its highest point, the serpentine gorge plunged 1,829 meters (6,000 feet) from rim to river bottom, making it one of the deepest canyons in the United States. In just 6 million years, water had carved through rock layers that collectively represented more than 2 billion years of geological history.

“The wonders of the Grand Canyon cannot be adequately represented in symbols or speech,” Powell wrote in his log. Powell was seeing the canyon mainly from river level; there was no technology that provided views of the landscape from space then. If there had been, he would have seen something similar to what Landsat 8 observed in March 2013.

The Colorado River traces a line across the arid Colorado Plateau. Treeless areas are beige and orange; green areas are forested. The river water is brown and muddy, a common occurrence in spring when melting snows cause water levels to swell and pick up extra sediment.

It took Powell months to navigate the gorge. By the time he had arrived in the area that is now Lake Mead (far left, second image), his men were weary and four had deserted. For water and sediment transported by the Colorado, the journey is much quicker; it takes just a handful of days.

Megadunes and Desert Lakes

-

Mongolia

In the Badain Jaran, nearly 100 lakes mingle with the tallest sand dunes in the world. Researchers have long studied these features in China, yet mystery continues to enshroud them.

Situated in the Alxa Desert region of Inner Mongolia, the Badain Jaran naturally piles up megadunes towering 200 to 300 meters (650 to 1,000 feet) tall. Scientists are still puzzling over how the dunes grow so large, investigating a combination of wind patterns and underlying geology.

Another enigma is the source of water for the lakes. Scientists are working to figure out the relative contributions from precipitation, groundwater, snowmelt, and paleowater. Regardless of the water source, they know that some lakes have shrunk or disappeared in recent years.

Colorful Faults of Xinjiang

-

China

Just south of the Tien Shan mountains, in northwestern Xinjiang province, a remarkable series of ridges dominates the landscape. The hills are decorated with distinctive red, green, and cream-colored sedimentary rock layers. The colors reflect rocks that formed at different times and in different environments. The red layers near the top of the sequence are Devonian sandstones formed by ancient rivers. The green layers are Silurian sandstones formed in a moderately deep ocean. The cream-colored layers are Cambrian-Ordovician limestone formed in a shallow ocean.

Landsat 8 captured this image of the Keping Shan thrust belt in July 2013. When land masses collide, the pressure can create what geologists call “fold and thrust belts.” Slabs of sedimentary rock that were laid down horizontally can be squeezed into wavy anticlines and synclines. Sometimes the rock layers break completely, and older layers of rock pile up on top of younger layers.

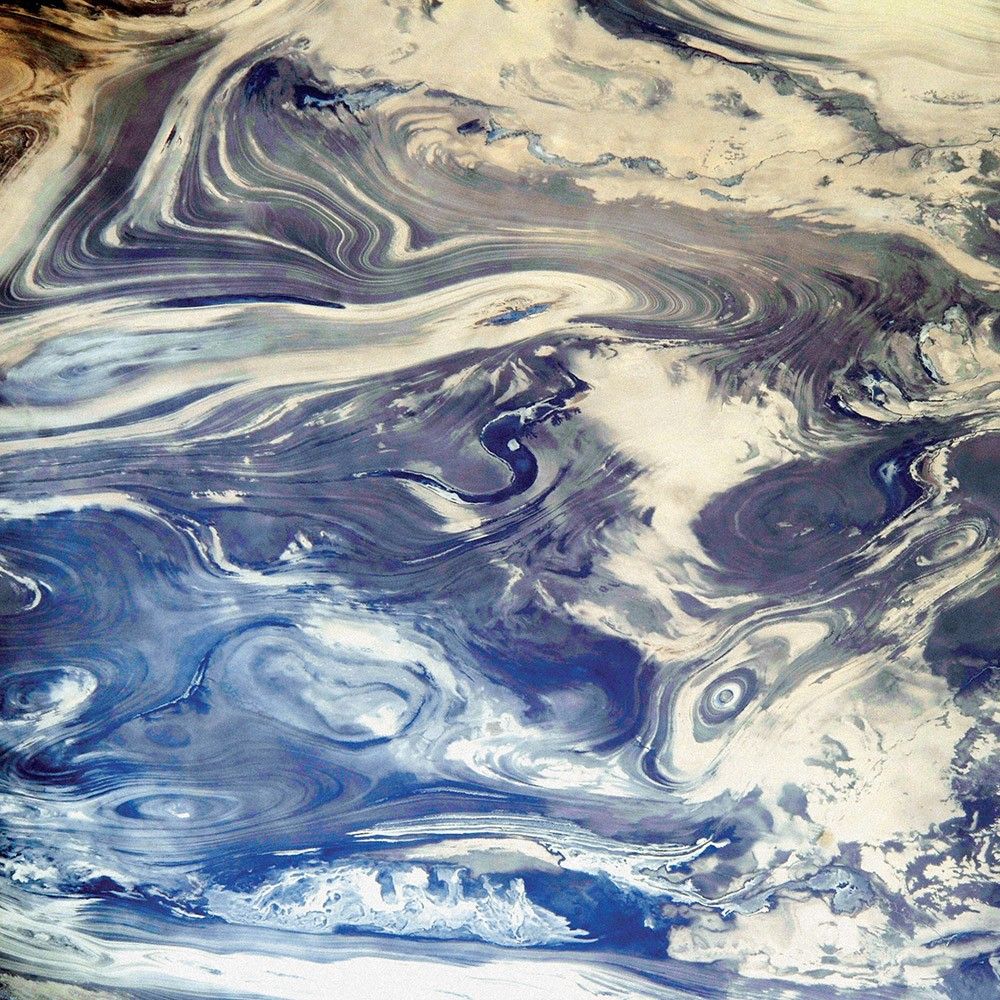

Bowknot Bend

-

United States

This section of the Green River canyon in eastern Utah is known as Bowknot Bend because of the way the river doubles back on itself. The loop carries river rafters 14.5 kilometers (9 miles) before bringing them back to nearly the same point they started from—though on the other side of a low, narrow saddle. The reason for the tight bends in the Green River is the same as it is for the mighty Mississippi: river courses often wind over time when they flow across a bed of relatively soft sediment in a floodplain.

In this January 2014 photograph taken from the International Space Station, the Green River appears dark because it lies in deep shadow, 300 meters (1,000 feet) below the surrounding landscape. The yellow-tinged cliffs that face the rising Sun give a sense of the steep canyon walls. The straight white line across the scene is the contrail from a jetliner.

From Rainforest to Rain Shadow

-

United States

Within a three-hour drive across Oregon, you can visit a beach, a temperate rainforest, a mountain glacier, and the high desert. The diversity of the landscape is mostly driven by the interaction of air masses and mountains.

This false-color Landsat 5 image from October 2011 shows the bare soil and sparse vegetation of the high desert in shades of pink, together with the deep-green vegetation on the west side of the Cascade Mountains. The one blue spot is the glacial cap of Mount Hood.

The transition from green to brown is indicative of a “rain shadow.” Winds blowing from the west carry moisture from the Pacific Ocean. As the air moves up into the mountains, it cools and the pressure decreases; the moisture condenses and falls out as rain or snow. On the eastern side, as the elevation drops, the air pressure increases and the air warms, effectively shutting off precipitation because the air can better hold the remaining moisture.

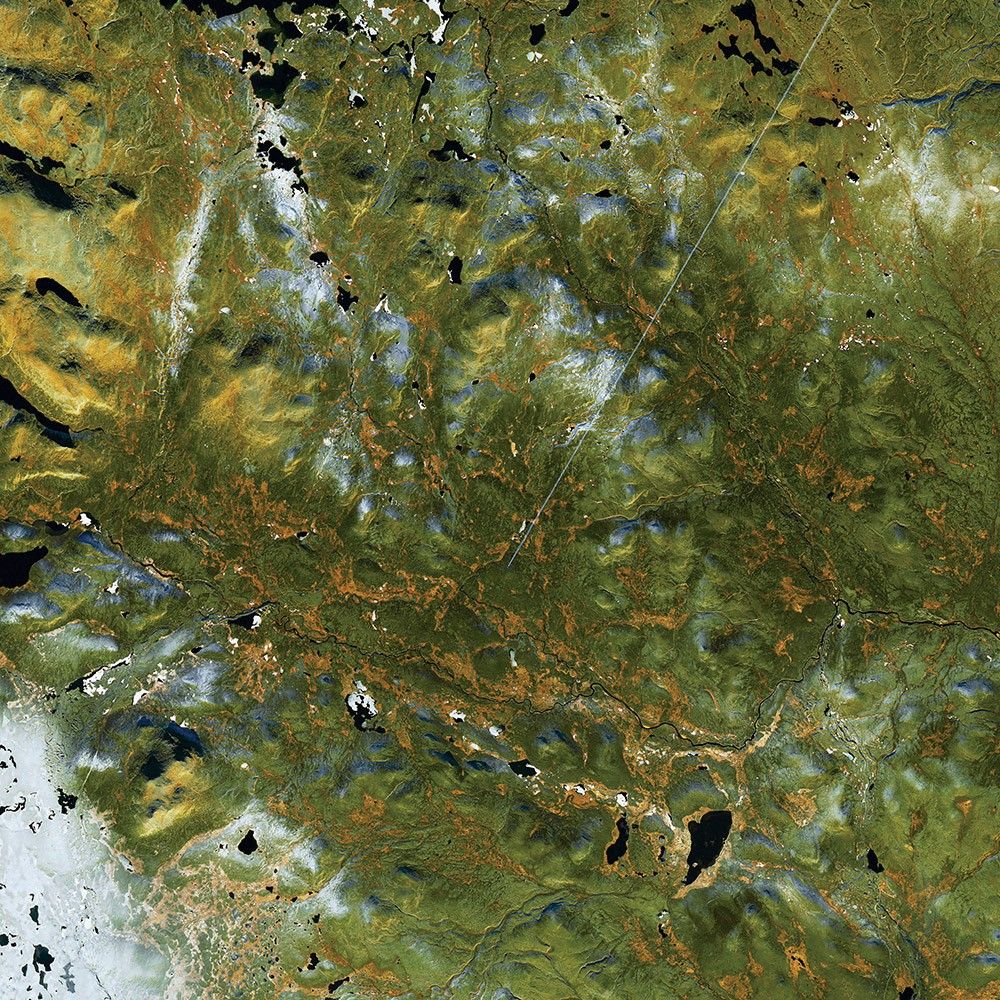

A Blaze of Color

-

Sweden

Fall in northern Sweden is a brief but spectacular affair. Alpine forests in this remote part of Lapland turn blazing shades of yellow and orange. Landsat 8 captured this image in October 2016.

Birch forests growing along stream valleys are probably the source of most of the color here, though other deciduous shrubs and understory plants surely contribute as well. Some of the hills have a dusting of snow. The southern Sun’s low angle above the horizon draws long, dark shadows across the landscape.

In autumn, the leaves on deciduous trees change colors as they lose chlorophyll, the pigment that helps plants synthesize food. When days shorten and temperatures drop, levels of chlorophyll (which appears green) do as well. Other leaf pigments—carotenoids and anthocyanins—then show off their colors.

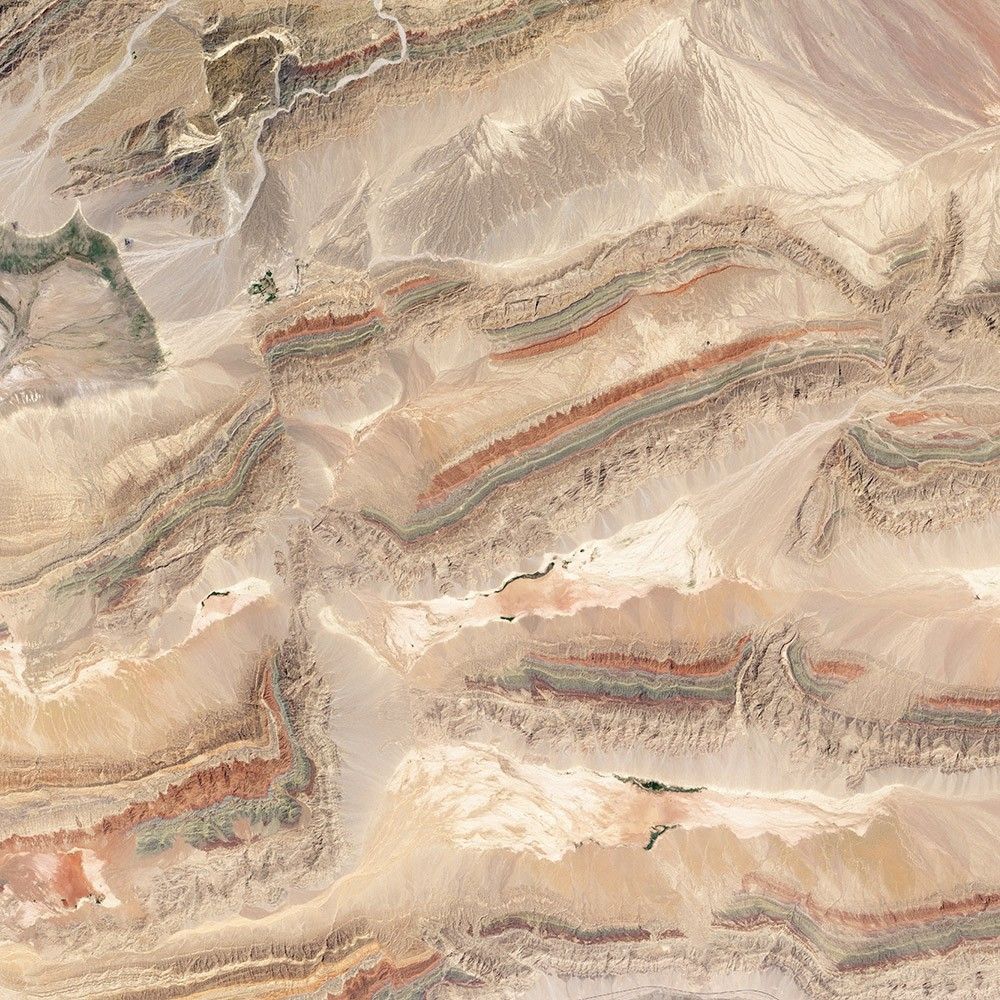

Folds and Curves of the Kavir

-

Iran

When astronauts pass over the deserts of central Iran, they are greeted by a striking pattern of parallel lines and sweeping curves. The lack of soil and vegetation in the Kavir desert (Dasht-e Kavir) allows the geological structure to appear quite clearly.

The patterns result from the gentle folding of numerous, thin layers of rock. Later, erosion by wind and water cut a flat surface across the dark- and light-colored folds, not only exposing hundreds of layers but also showing the shapes of the folds. The pattern has been likened to the layers of a sliced onion.

The dark water of a lake (image center) fills a depression in a more easily eroded, S-shaped layer of rock. A small river snakes across the bottom of this October 2014 photograph taken from the International Space Station.

Fanning Out in Farmland

-

Kazakhstan

Mountain streams are usually confined to narrow channels and tend to transport large amounts of gravel, sand, clay, and silt—what geologists call alluvium. When such a stream pours onto a relatively flat valley or basin, it often spreads out to into multiple, interlacing channels. Over time, the channels migrate back and forth, creating fan-shaped deposits known as alluvial fans.

Landsat 8 captured this view of Kazakhstan’s Almaty Province in September 2013. On the lower left, the Tente River flows through the foothills of the Dzungarian Alatau range. Where the Tente emerges, it spreads out and becomes a braided stream. The movement of the channel over time has left a large alluvial fan. In arid areas, these fans are often used for agriculture because they are relatively flat and provide groundwater for irrigation. The blocky green patterns show fields or pasture land.

The Zones of Kilimanjaro

-

Tanzania

Stories about Mount Kilimanjaro often focus on its height and location. The tallest mountain in Africa is capped with snow and ice, despite sitting near the Equator. But it is also compelling for a different reason: To get to the icy summit, you must pass through incredibly diverse vegetation zones. The mountain rises from the hot, dry savanna, through rainforest and hardy scrublands, to a rocky and icy summit.

People have cultivated the lowlands ringing the mountain, which appear as patchy green areas. The continuous dark-green band is montane forest, which stretches from roughly 1,800 to 2,800 meters in elevation. The dark-green areas transition to a band of green- brown known as the moorland zone—colder, less humid, and full of short, hardy plants. The highest areas—the alpine desert and summit zones—are inhospitable to all but the most skilled mountain climbers.

Liwa Oasis

-

United Arab Emirates

In the sandy tan terrain of the United Arab Emirates, on the northern edge of the Rub’ al Khali, an oasis brings green to the desert. The T-shaped, 100-kilometer stretch of date plantations and small towns compose the Liwa Oasis, home to about 20,000 people in the emirate of Abu Dhabi. It is one of the largest oases on the Arabian Peninsula.

Bedouins tapped underground water supplies here at least five centuries ago, and date farms have proliferated. Drip irrigation and greenhouses now help conserve the precious water supply. Since rainfall is scarce in the region, much of the water comes from aquifers full of “fossil” water that accumulated more than 20,000 years ago and is now buried deep under the sand seas and limestone formations.

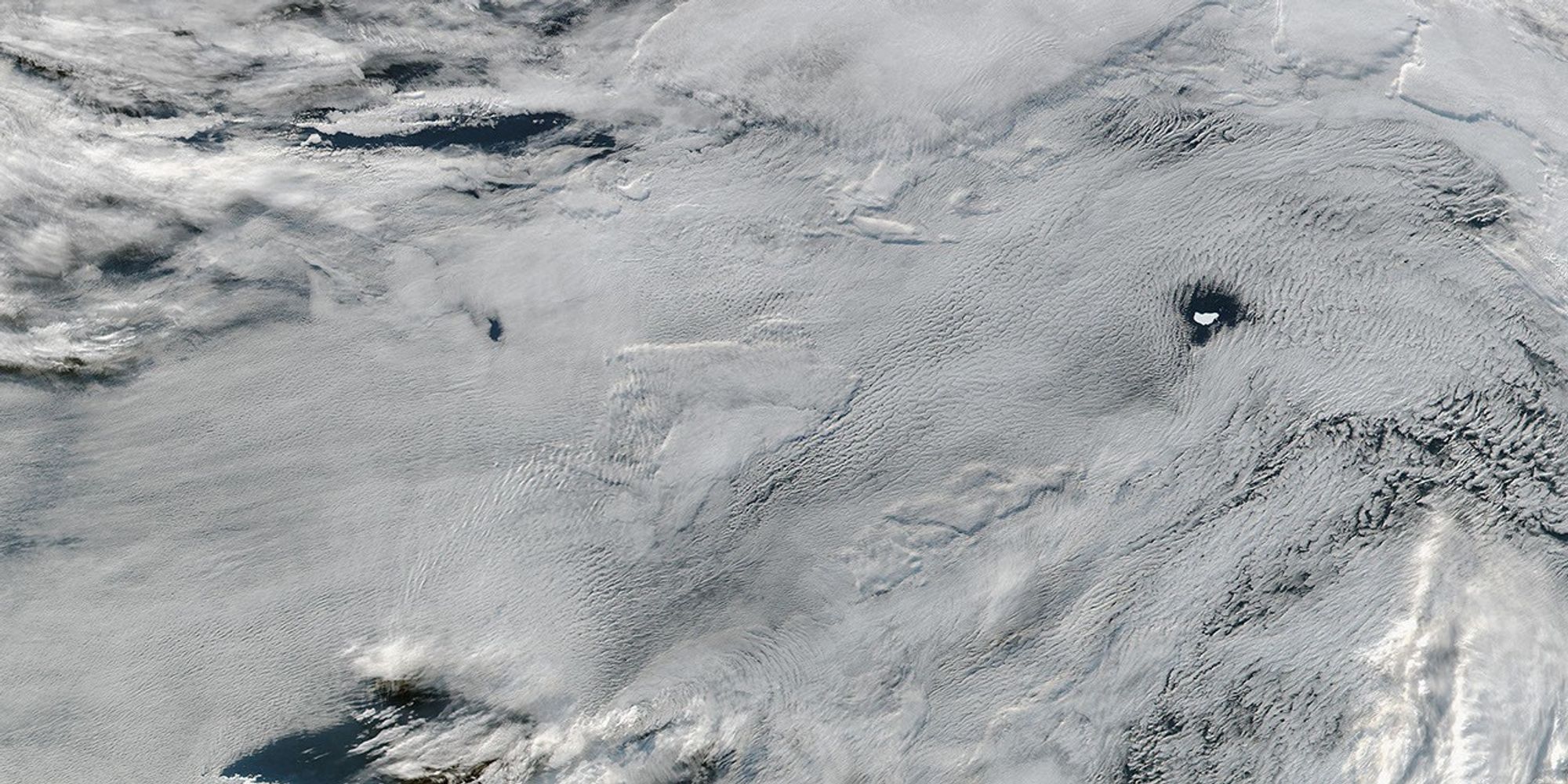

Don Juan Pond

-

Antarctica

In a valley in one of the most extreme environments on Earth lies the world’s saltiest body of water. It rarely snows and never rains in the McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica. Winter temperatures can drop to –50° Celsius, and the few ponds and lakes are capped by ice that is several meters thick.

Then there’s Don Juan Pond. The ankle-deep pond in Upper Wright Valley is so salty that its calcium chloride-rich waters rarely freeze. With a salinity level of over 40 percent, Don Juan is significantly saltier than the Dead Sea and the Great Salt Lake.

The Earth Observing-1 satellite captured this image in January 2014. The ellipse-shaped lake is situated at the bottom of a basin between the Dais plateau and the Asgard Range to the south. It has a slightly darker hue than the salt-encrusted lake bottom around it.

Linear Dunes, Caprivi Strip

-

Namibia

In far northeastern Namibia, there is a skinny stretch of land sandwiched between Angola, Botswana, and Zambia. The Caprivi Strip receives about 600 millimeters (24 inches) of rainfall each year. That’s not a lot of rain—it tends to come in bursts that cause periodic floods—and it is a stark contrast to the much drier parts of the country.

Here the land is striped, as if a giant had dragged a rake over the landscape. Those stripes are linear dunes, and some of them are more than 100 kilometers (60 miles) long. Dunes generally form from wind-blown sand over many years, and one characteristic of linear dunes is that they tend to remain intact long after the dry conditions cease. And because they don’t migrate like marching dunes, linear dunes preserve dirt and rocks that geologists can later use to understand past conditions.

Harratt Lunayyir Lava Field

-

Saudi Arabia

In northwestern Saudi Arabia lies a field of volcanic lava. Known as Harratt Lunayyir, the lava field contains some 50 cones from volcanic eruptions over the past 10,000 years. The Terra satellite captured this false-color image in October 2006. Old lava flows appear as irregular, dark stains on an otherwise light-colored landscape. Like ink on an uneven surface, the lava has formed rivulets of rock that flow out in all directions.

Although one of the volcanic cones may have erupted as recently as the 10th century CE, scientists long believed the region to be geologically quiet until a seismic swarm and the opening of a crevice in 2009 suggested otherwise. The lava field Harratt Lunayyir lies about 200 kilometers (120 miles) from the tectonic spreading center under the Red Sea; magma can rise along the margins of such areas.

Taranaki and Egmont

-

New Zealand

The circular pattern of New Zealand’s Egmont National Park stands out from space as a human fingerprint on the landscape. The park protects the forested and snow-capped slopes around Mount Taranaki (Mount Egmont to British settlers). It was established in 1900, when officials drew a radius of 10 kilometers around the volcanic peak. The colors differentiate the protected forest (dark green) from once-forested pasturelands (light- and brown-green).

Named by the native Maori people, Taranaki stands 2,518 meters (8,260 feet) tall, and it is one of the world’s most symmetric volcanoes. It first became active about 135,000 years ago. By dating lava flows, geologists have figured out that small eruptions occur roughly every 90 years and major eruptions every 500 years. Landsat 8 acquired this image of Taranaki and the park in July 2014.

Cultivating a Border

-

China and Kazakhstan

While people often say borders are not visible from space, this line between eastern Kazakhstan and northwestern China could not be clearer. The border is made visible due to land-use policies.

With limited arable land and a large human population to feed, China farms just about any land that can be sustained for agriculture. In this Landsat 8 image from September 2013, fields are dark green in contrast to the surrounding dry landscape, a sign that the farms are irrigated.

While agriculture is important in the Kazakh economy, eastern Kazakhstan is a minor growing area for that country. A few rectangular shapes show that farming does occur. Much of the agriculture on the Kazakh side is rain-fed, so fields are tan like the surrounding, natural landscape.

Barrier Islands

-

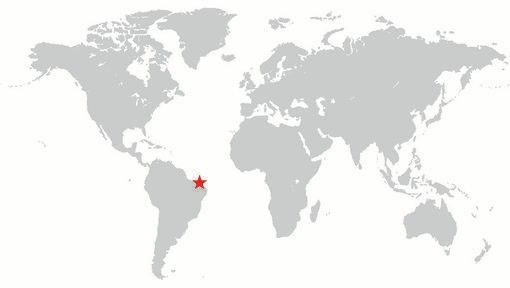

Brazil

Barrier islands are narrow strips of sand—often spits or sandbars that grow into full-blown, vegetated islands. They stretch from a few hundred meters to several kilometers wide. They run parallel to the coast, facing the sea, bearing the brunt of waves and wind, and protecting lagoons, bays, and coastal wetlands. And they move constantly, shaped and reshaped by currents, tides, people, and winds.

Barrier islands are found along the edge of every continent except Antarctica, and scientists and naturalists are still finding new ones. In June 2006, Landsat 5 captured this image of previously unrecognized barrier islands along the coast of Brazil between the Amazon River and São Luís. Brazil has the world’s longest continuous chain of barrier islands—54 in total—extending more than 570 kilometers (350 miles) along the Atlantic coast.

Tsauchab River Bed

-

Namibia

The Tsauchab River is a famous landmark for the people of Namibia and tourists. Yet few people have ever seen the river flowing with water. In times past, when the climate was more temperate, the Tsauchab likely reached the Atlantic coast, 55 kilometers to the west.

Like several other rivers around the Namib Desert, the Tsauchab brings sediment down from the hinterland toward the coastal lowland. This sediment is then blown from the river beds, and over tens of millions of years it has accumulated as the red dunes of the Namib Sand Sea.

In December 2009, an astronaut on the International Space Station caught this glimpse of the Tsauchab River bed jutting into the sea of red dunes. It ends in a series of light-colored, silty mud holes on the dry lake floor.