World of Change: Snowpack in the Sierra Nevada

- World of Change: Padma River

- World of Change: Sprawling Shanghai

- World of Change: Ice Loss in Glacier National Park

- World of Change: Development of Orlando, Florida

- World of Change: Growing Deltas in Atchafalaya Bay

- World of Change: Coastline Change

- World of Change: Managing Fire in Etosha National Park

- World of Change: Green Seasons of Maine

- World of Change: Columbia Glacier, Alaska

- World of Change: Athabasca Oil Sands

- World of Change: Seasons of the Indus River

- World of Change: Global Temperatures

- World of Change: Seasons of Lake Tahoe

- World of Change: Devastation and Recovery at Mt. St. Helens

- World of Change: Collapse of the Larsen-B Ice Shelf

- World of Change: Mountaintop Mining, West Virginia

- World of Change: Yellow River Delta

- World of Change: Drought Cycles in Australia

- World of Change: El Niño, La Niña, and Rainfall

- World of Change: Severe Storms

- World of Change: Burn Recovery in Yellowstone

- World of Change: Global Biosphere

- World of Change: Antarctic Ozone Hole

- World of Change: Amazon Deforestation

- World of Change: Antarctic Sea Ice

- World of Change: Shrinking Aral Sea

- World of Change: Arctic Sea Ice

- World of Change: Water Level in Lake Powell

- World of Change: Mesopotamia Marshes

- World of Change: Solar Activity

- World of Change: Urbanization of Dubai

Sierra Nevada is a Spanish name that means “snowy mountain range.” While the term “snowy” has generally been true for most of American history, the mountain range has seen several years of snow drought in the 21st century.

The depth and breadth of the seasonal snowpack in any given year depends on whether a winter is wet or dry. Wet winters (such as 2017 and 2023) tend to stack up a deep snowpack, while dry ones keep it shallow. In 2015, long-term hot and dry conditions in California and Nevada brought snowpack to historically low levels.

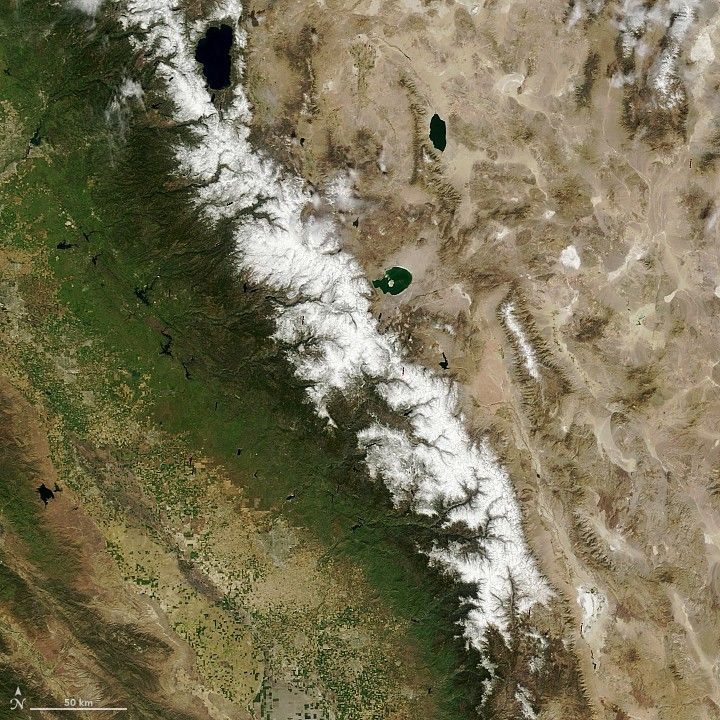

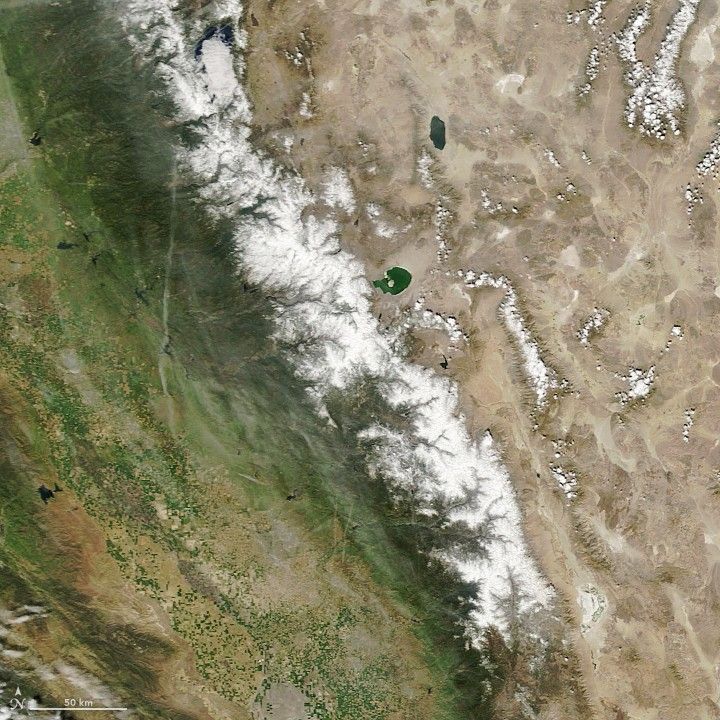

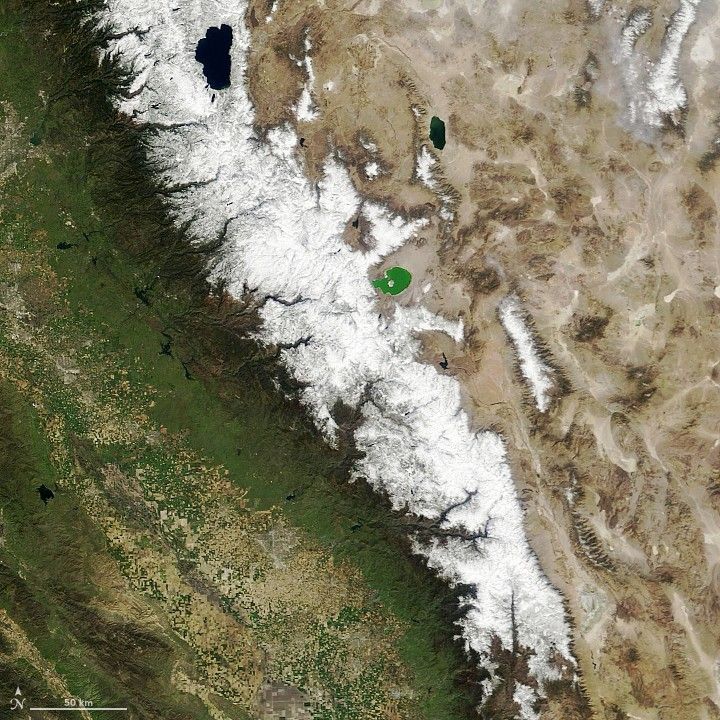

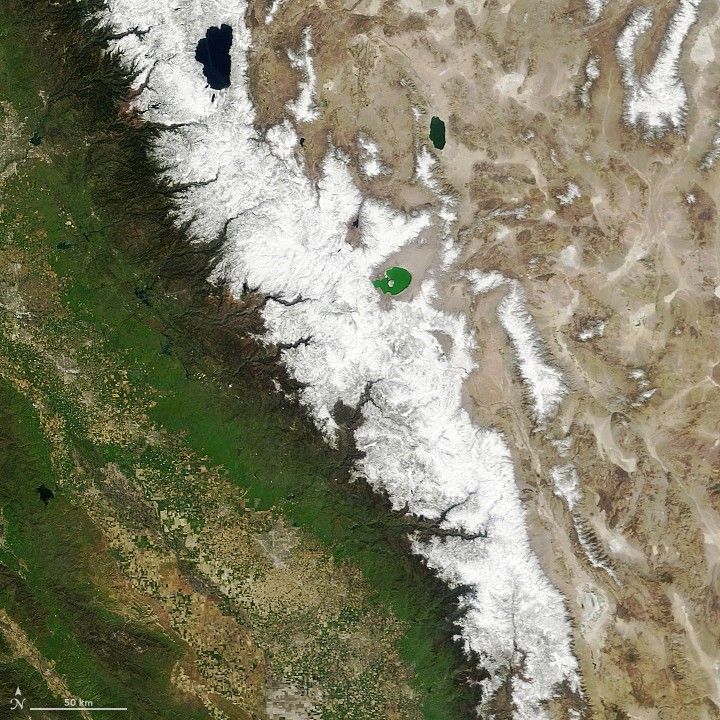

This series of images shows the snowpack on the Sierra Nevada from 2006 to 2024. The natural-color images were acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Terra satellite. Each image was acquired around April 1, halfway through the water year. A “water year” is the 12-month period from October 1 through September 30. The snowpack on the Sierra Nevada has generally peaked and begins to melt by the beginning of April. Meltwater runoff from that snowpack helps replenish rivers and reservoirs while recharging the groundwater.

The series begins in 2006, which was a wet year with substantial snowfall. Then dry water years struck from 2007–2009—the first time in California’s history that statewide declarations of emergency were issued for drought, according to the California Department of Water Resources. In 2009, the proclamation noted that rainfall and snowpack deficits were putting California “further and further behind in meeting its essential water needs.”

Wet years returned from 2010–2011. The wet year of 2011 buffered the initial effects of drought that returned in 2012, but dry conditions deepened in subsequent years. By March 2015, about one-third of the ground-based monitoring sites in the Sierra Nevada recorded the lowest snowpack ever measured. Some sites reported no snow for the first time. One month later, only some sites—generally those at higher elevations—had any measurable snowpack.

Scientists from the University of Arizona wrote in a September 2015 article in Nature Climate Change that the low snowpack conditions of 2015 were truly extraordinary. Tree-ring records of precipitation anomalies and of temperature allowed them to reconstruct a 500-year history of snow water equivalent in the Sierra Nevada. The researchers found that the low snowpack of April 2015 was “unprecedented in the context of the past 500 years.”

El Niño conditions in 2015–16 brought substantial rain and snowfall back to the mountains, but snow cover still fell short of long-term averages. Then a steady stream of atmospheric river events brought double the long-term average of rain and snow to the Sierra Nevada between October 2016 and April 2017.

With a dramatic exception in 2019, the 2018–22 period was marked by below-average snowfall. Extreme drought plagued the western U.S. between 2020 and 2023, in part due to a “triple-dip“ La Niña. As La Niña started to wane in early 2023, a deluge of atmospheric rivers brought an unusually wet winter to California. The cold and wet winter resulted in a boom year for snow in the Sierras. According to the California Department of Water Resources, 2023 saw the highest snowpack since 1952.

Although 2024 started off dry, late winter storms replenished the range’s frozen reservoir. After more than a decade of either unusually wet or unusually dry years, snowpack that year was uncharacteristically close to average.

References and Related Reading

- Belmecheri, S. et al. (2015, September 14) Multi-century evaluation of Sierra Nevada snowpack. Nature Climate Change, advance online publication.

- California Department of Water Resources (2015, February) California’s Most Significant Droughts: Comparing Historical and Recent Conditions. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- The Guardian (2015, October 9) Global warming is shrinking California’s critical snowpack. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Cener (2015, September 30) Observing Drought in California with Remote Sensing. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- NASA Making Earth System Data Records for Use in Research Environments (MEaSUREs) project (2015) Northern Hemisphere Snow and Ice Climate Data Records. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- The New York Times (2015, September 14) Study Finds Snowpack in California’s Sierra Nevada to Be Lowest in 500 Years. Accessed April 13, 2016.

- United States Department of Agriculture (2015, March 11) Record Low Snowpack in Cascades, Sierra Nevada. Accessed April 13, 2016.