Brandon Rodriguez

Education Specialist

Contents

- You were born in Venezuela and came to the U.S. when you were 12 years old. Tell us the story of why and how you came to America.

- Who took care of you and your sister in the U.S.?

- In high school, you acted out and struggled with chemistry. How did you get through it?

- You ended up graduating at 16 and making your way to Nashville for college at Vanderbilt University. What was that like?

- What first sparked your interest in space and science?

- How did you end up working in the space program?

- Tell us about your job. What do you do?

- What have been some of your favorite projects to work on?

- You still wake up every morning and teach an 8 a.m. physics class at a charter school before heading to JPL. Why did you want to teach in addition to your full-time job?

- Who inspires you?

- What’s one piece of advice you would give to others interested in a similar career?

- What are some fun facts about yourself or something people might not know about you?

- What is your favorite space image and why?

- Where are they from?

You were born in Venezuela and came to the U.S. when you were 12 years old. Tell us the story of why and how you came to America.

My sister and I immigrated to escape during Hugo Chavez’s presidency. Our father, in his youth, was very vocal in opposing him and that did not bode well for my family. We were lucky to get to Canada and stay for several years before receiving visas to live in the United States. With the support of adopted family members, both my sister and I were able to attend good schools and open doors that never would have been available to us. My sister and I both went on to teach high school science in hopes of opening doors for future scientists that may be in a similar position.

Who took care of you and your sister in the U.S.?

I didn’t have family here, but I was taken in by friends and adopted family. In high school and college, the kindness of strangers meant things like giving me a place to stay or even buying me clothes. I especially remember how, in college, my peers would invite me over for Thanksgiving and other holidays. They gave me a community when I felt alone.

In high school, you acted out and struggled with chemistry. How did you get through it?

I was a jerk in high school. It’s tough when you have a lot going on outside of school. You act out in some way—someone has to be the target of all of that venting and angst. A lot of things at home drove me to misbehave in school. I was always talking in class, looking for fights and never thinking about the consequences of my actions. Teachers found creative ways to keep me working. I was bad at chemistry in high school; it was the hardest for me and I didn’t understand why. I had a great teacher who effectively tricked me—he took all of my bad behavior and acting out and told me one day, “If you think you’re so cool, compete in the state science Olympics. If you can do that, you don’t have to take the tests in my class.” I ended up getting the gold medal, without catching on that I spent more time preparing for that event than I ever would have studying for his exams.

You ended up graduating at 16 and making your way to Nashville for college at Vanderbilt University. What was that like?

It was a major culture shock. I was still very much a poor immigrant kid surrounded by a school that was 98 percent white. The average family income was approximately $200,000 a year. I got a full scholarship—the only way I could ever attend a school like that—whereas my peers were writing a check for all four years. It was odd but I eventually found a group, people who were exploring things like me. I remember being shocked by how few Latin people there were in the entire school, though. I knew I would never speak another word of Spanish.

“I was always really interested in science when I was young, simply because of the challenge of it. It never really came easy for me, which is why I think I stuck with it—I wanted to figure it out.” – Brandon Rodriguez

What first sparked your interest in space and science?

I was always really interested in science when I was young, simply because of the challenge of it. It never really came easy for me, which is why I think I stuck with it—I wanted to figure it out. My interest in space, however, is pretty new. I came to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory with no space science background or aspirations of working for NASA. It really is just the same feeling I had as a kid, however, except that now I’m surrounded by thousands of like-minded people. The way I explain it is that I’m a nerd first and a scientist second. What better place to work?

How did you end up working in the space program?

After school, I worked in the private sector doing chemical research for seven years. I loved my job and was able to travel all over the world. However, I started really feeling that it was time to give back to my community, so I began teaching high school science in inner-city schools in Houston. In 2016, a position at JPL opened up in education that effectively allowed me to combine my two passions.

Tell us about your job. What do you do?

I work in the education department as an education specialist providing resources and training to K-12 schools across California. I get to work with an amazing team to develop content for classroom teachers, visit schools and speak with students, and train future teachers to bring NASA into their classrooms.

What have been some of your favorite projects to work on?

Each year we lead a one-week institute for 50 soon-to-be teachers in the area. It’s so exciting to take these young teachers and give them the tools to hit the ground running. So many amazing people from JPL volunteer their time to share current NASA science, which we pair with classroom activities. It’s the ideal union of science and education to really equip the classrooms of tomorrow.

You still wake up every morning and teach an 8 a.m. physics class at a charter school before heading to JPL. Why did you want to teach in addition to your full-time job?

Because I’m a crazy person. When I first pitched this idea to my manager, I was almost hoping he’d say no. But the truth is that I really feel so much better about my role knowing that we’re not “telling” teachers what to do from our ivory tower. Instead, I can “share” with teachers what I know works not just in theory, but because I’m still there in the classroom doing it myself.

Who inspires you?

I still am really moved by writers like Thomas Kuhn and Imre Lakatos. I think as scientists, their works should be required reading. Science is so much more than a method of day-to-day tasks and procedures—it’s a mindset and a practice.

What’s one piece of advice you would give to others interested in a similar career?

Get uncomfortable. I’ve been at JPL for three years now and I’m still drinking from the fire hose every single day. I think I have learned and developed so much more when I just accepted that I will always be lost and always learning. Oddly enough, the most intimidating times don’t come from rooms of scientists, but from groups of kids—their imaginations are so wild, it’s impossible to know enough to ever really satisfy them!

What are some fun facts about yourself or something people might not know about you?

I’ve traveled to all seven continents, a goal I was able to complete while in Antarctica looking at ice core samples.

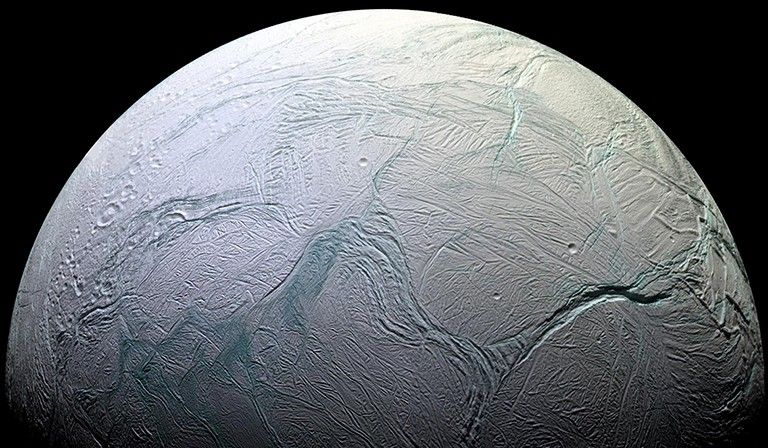

What is your favorite space image and why?

Absolutely impossible to pick, but pictures of Enceladus like these really get to me. It just inspires so much wonder for me about how little we know about our own backyard and how much is left to discover.

Where are they from?

Planetary science is a global profession.