A Twisted Tale

| PIA Number | PIA08325 |

|---|---|

| Language |

|

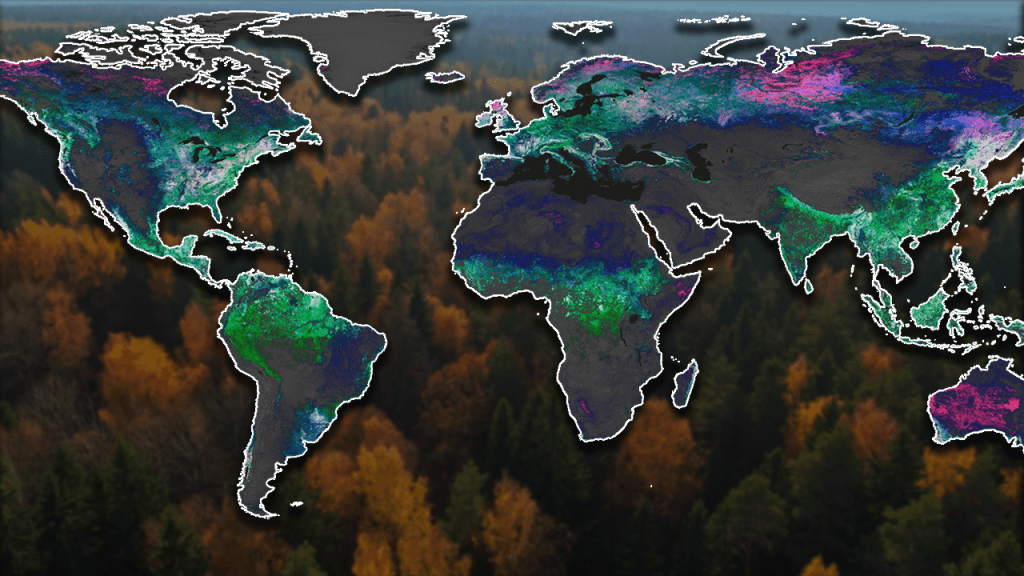

Saturn's D ring--the innermost of the planet's rings--sports an intriguing structure that appears to be a wavy, or "vertically corrugated," spiral. This continuously changing ring structure provides circumstantial evidence for a possible recent collision event in the rings.

Support for this idea comes from the appearance of a structure in the outer D-ring that looks, upon close examination, like a series of bright ringlets with a regularly spaced interval of about 30 kilometers (19 miles). When viewed along a line of sight nearly in the ringplane, a pattern of brightness reversals is observed: a part of the ring that appears bright on the far side of the rings appears dark on the near side of the rings, and vice versa (see D Ring Sight Lines).

This phenomenon would occur if the region contains a sheet of fine material that is vertically corrugated, like a tin roof. In this case, variations in brightness would correspond to changing slopes in the rippled ring material (see image with inset graphic).

An observation made with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope in 1995 also saw a periodic structure in the outer D ring, but its wavelength was then 60 kilometers (37 miles). There were insufficient observations to discern the spiral nature of the feature. Thus, it appears the wavelength of the wavy structure has been decreasing: that is, this feature has been winding up like a spring over time.

The rate at which the pattern appears to be winding up is quite close to the rate scientists would expect for a vertically corrugated spiraling sheet of material at this location in the rings that is responding to gravitational forcing from Saturn.

As Cassini imaging scientists extrapolated the spiraling trend backward in time, they found that it completely unwound in 1984, leaving only an inclined, or tilted, sheet of material. The researchers speculate such an inclined sheet may have been produced around that time by the impact of a comet or meteoroid into the D ring which kicked out a cloud of fine particles that ultimately inherited some of the tilt of the impactor's trajectory as it slammed into the rings. Another possibility is that the impactor struck an already inclined moonlet, shattered it to bits and the debris remained in an inclined orbit.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov . The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org .

Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute