Contents

- Maria on the Moon (1645)

- Totally Dry Moon (1892)

- Ideas of Water (1960s)

- Apollo Landings (1969 – 1972)

- Possible Frozen Water in Shadowed Craters (1994, 1998)

- Revisiting Apollo Samples (2008)

- Signs of Hydration (2009)

- Chandrayaan, Cassini, Deep Impact

- Observations of Lunar Debris Reveal More (2009 – 2019)

- Confirmation of Moon Water – Shadowed Regions (2018)

- Confirmation of Moon Water – Sunlit Surface (2020)

- First Detailed, Wide-Area Map of Water on the Moon (2023)

- More to Discover

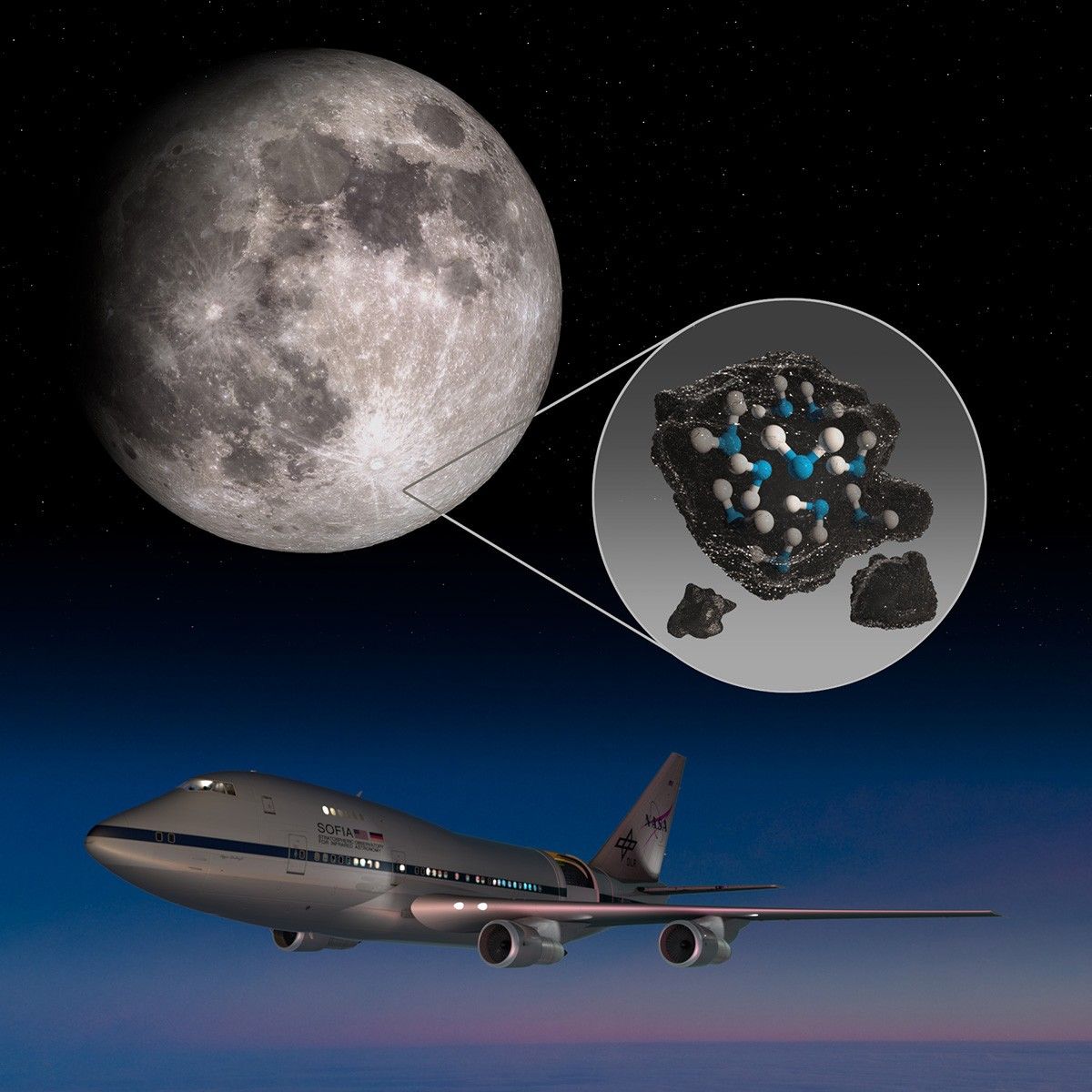

What’s big, covered in water, yet 100 times drier than the Sahara Desert? It’s not a riddle, it’s the Moon! For centuries, astronomers debated whether water exists on Earth’s closest neighbor. In 2020, data from NASA’s SOFIA mission confirmed water exists in the sunlit area of the lunar surface as molecules of H2O embedded within, or perhaps sticking to the surface of, grains of lunar dust. Here is a brief history of the discoveries leading up to the confirmation of water on the Moon.

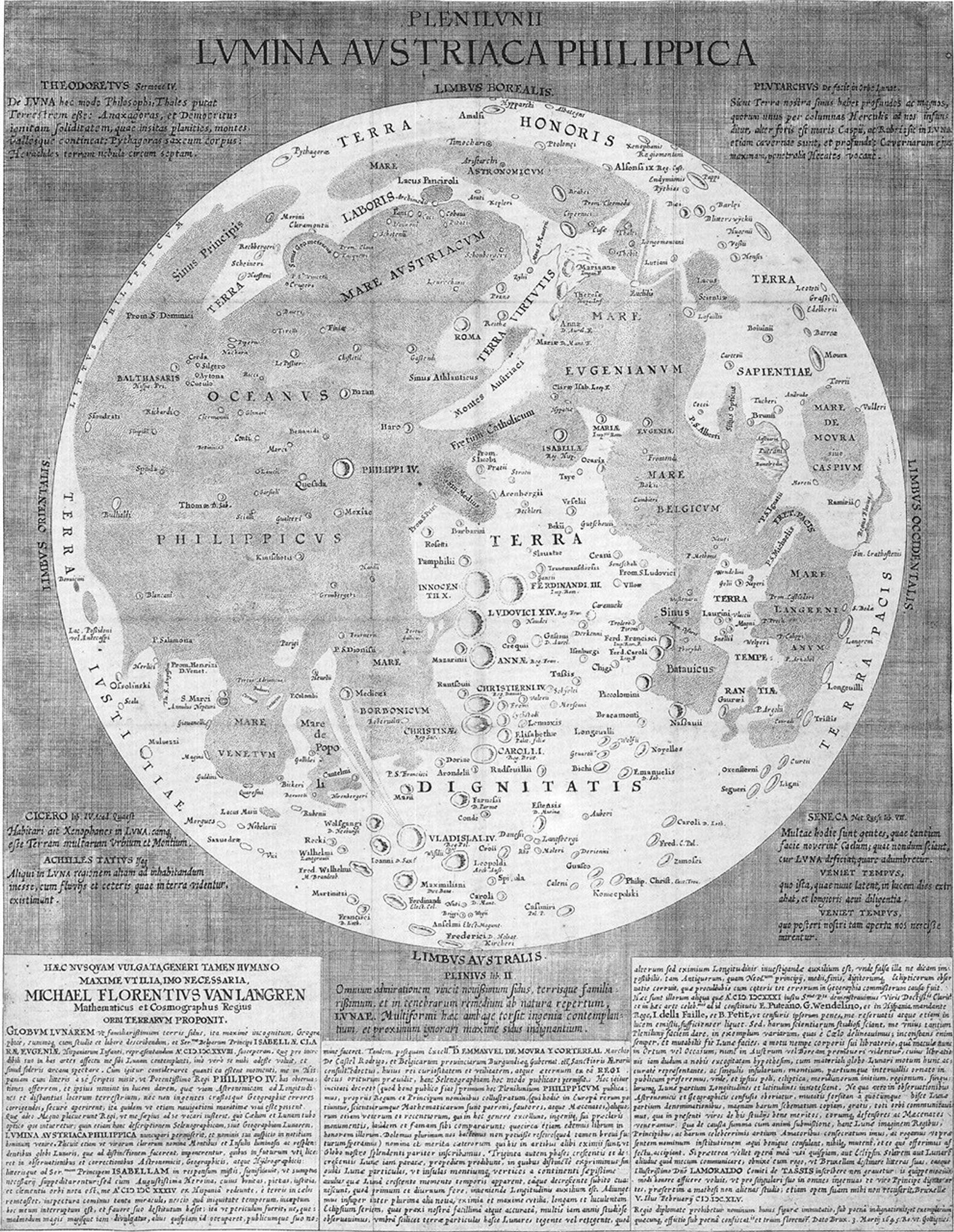

Maria on the Moon (1645)

When early astronomers looked up at the Moon, they were struck by the large, dark spots on its surface. In 1645, Dutch astronomer Michael van Langren published the first-known map of the Moon referring to the dark spots as “maria” – the Latin word for “seas” – and putting into writing the widely-held view that the marks were oceans on the lunar surface. Similar maps from Johannes Hevelius (1647), Giovanni Riccioli and Francesco Grimaldi (1651) were published over the next few years. We now know these spots to be plains of basalt created by early volcanic eruptions, but the nomenclature of ‘maria’ (plural) or ‘mare’ (singular) remains.

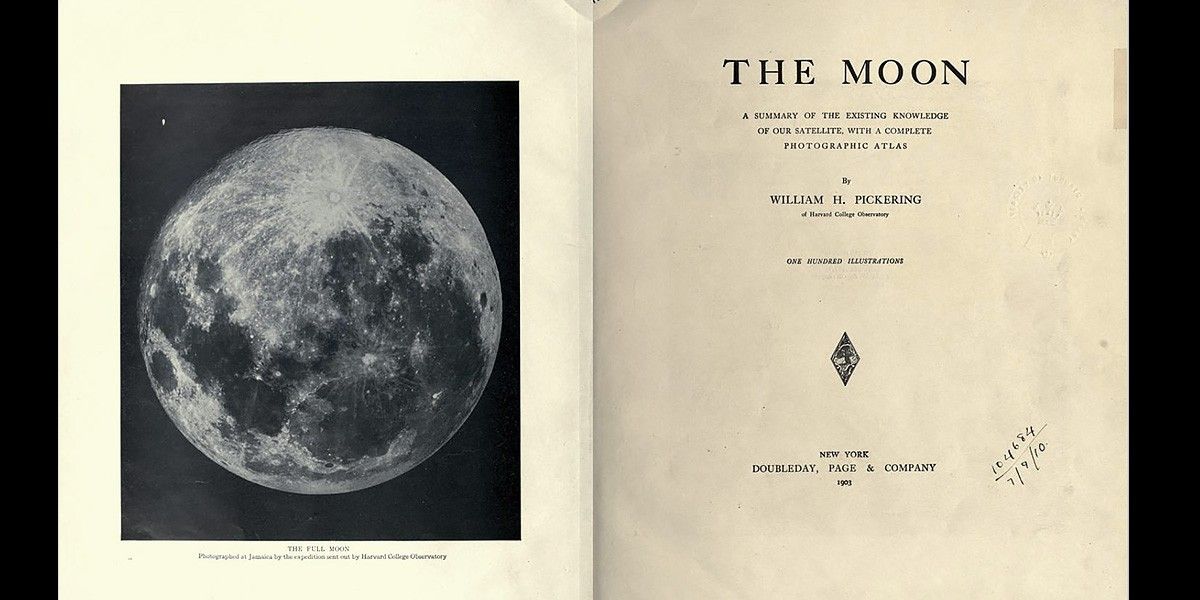

Totally Dry Moon (1892)

American astronomer William Pickering made measurements in the late 1800s that led him to conclude the Moon essentially has no atmosphere. With no clouds and no atmosphere, scientists generally agreed that any water on the lunar surface would evaporate immediately. Pickering’s measurements led to a widespread view that the Moon was devoid of water.

Ideas of Water (1960s)

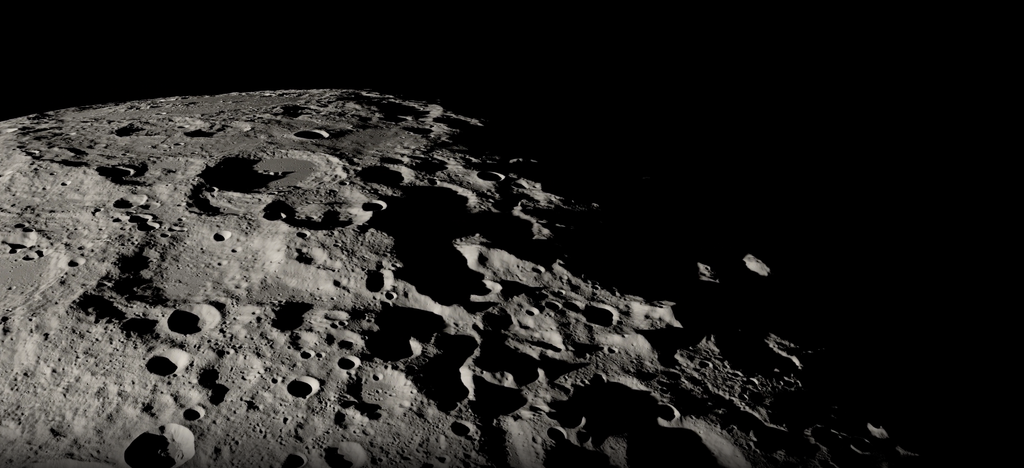

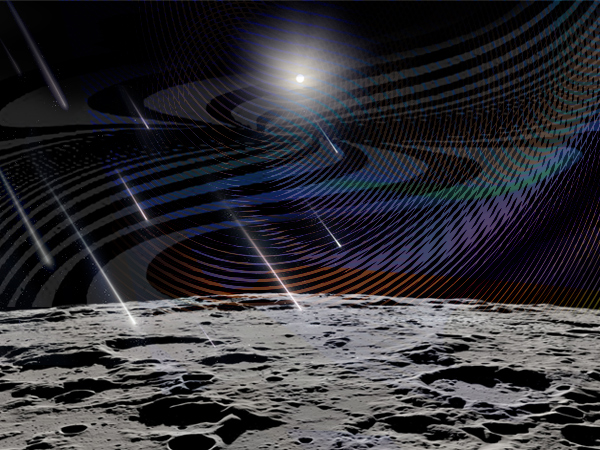

As scientists made headway in understanding the behavior of substances that are prone to vaporize at relatively low temperatures – called volatiles – theoretical physicist Kenneth Watson published a paper in 1961 describing how a substance like water could exist on the Moon. Watson’s paper first popularized the idea that water ice could stick to the bottom of craters on the Moon that never receive light from the Sun, while sunlit areas on the Moon would be so hot that water would evaporate near-instantly. These lightless areas of the Moon are called “permanently shadowed regions.”

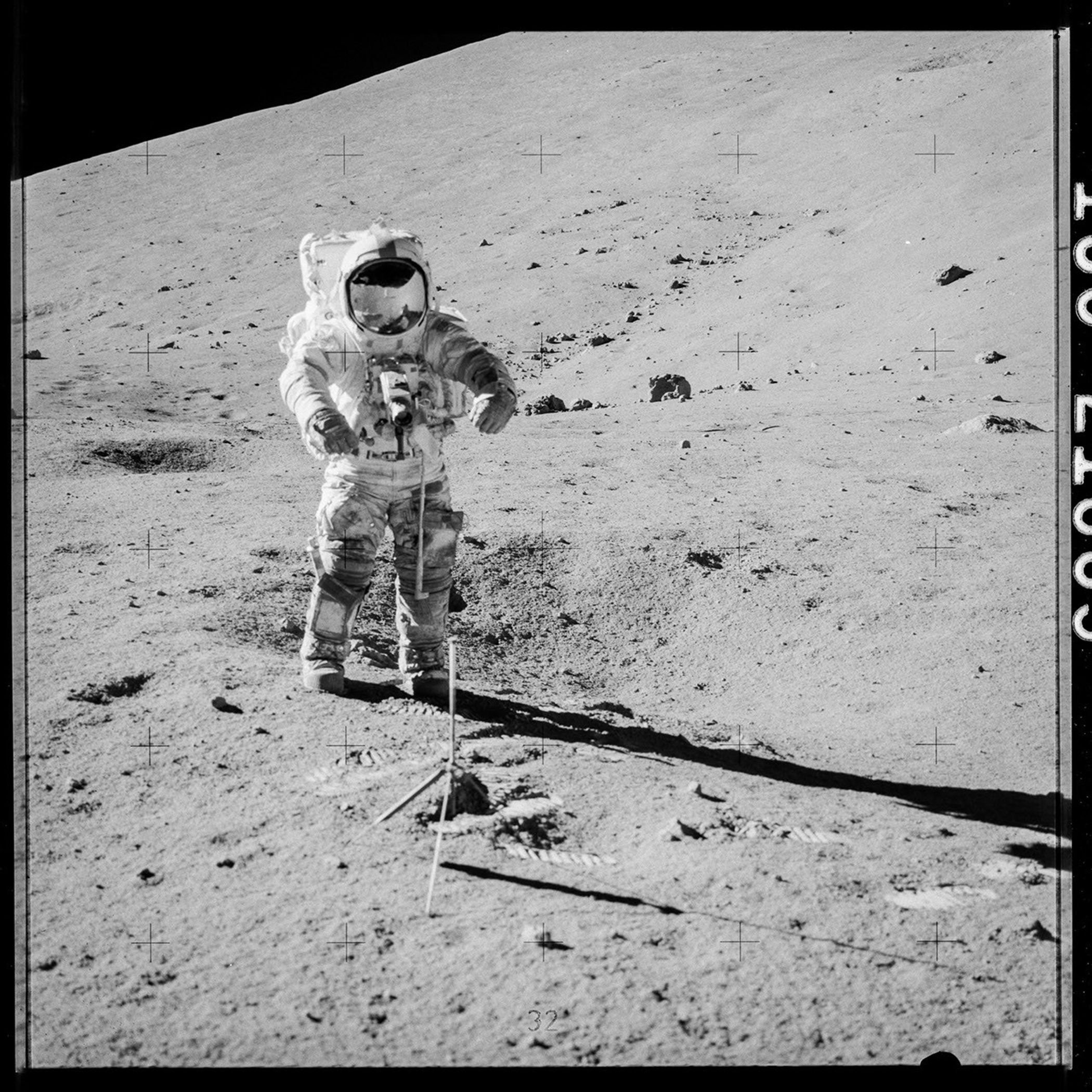

Apollo Landings (1969 – 1972)

The Apollo era brought humans to the lunar surface for the very first time, giving researchers the opportunity to directly look for signs of water on the Moon. When tested, soil samples brought back by Apollo astronauts revealed no sign of water. Scientists concluded that the lunar surface must be completely dry, and the prospect of water wasn’t seriously considered again for decades.

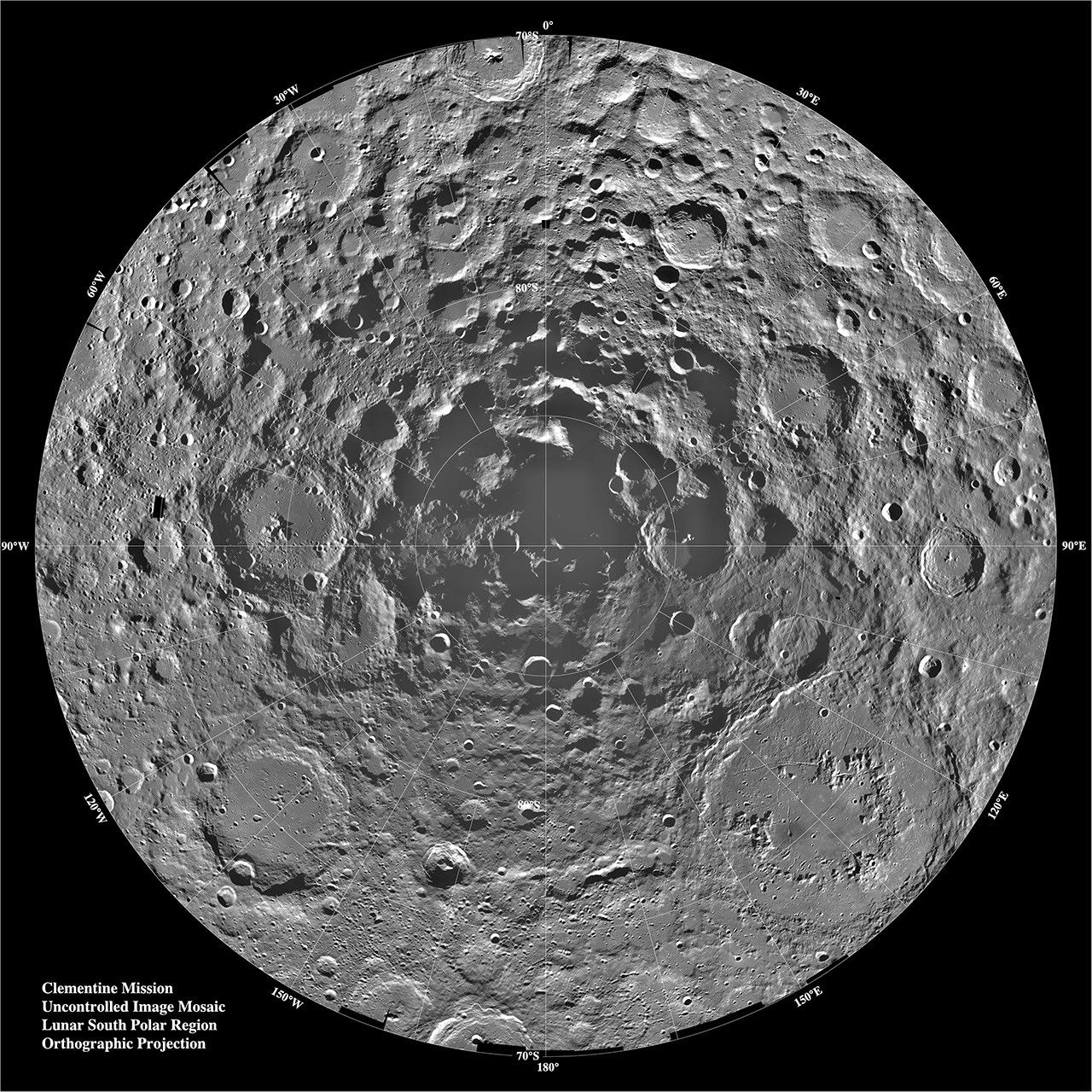

Possible Frozen Water in Shadowed Craters (1994, 1998)

NASA’s Clementine mission launched in 1994 to orbit the Moon for two months and collect information about its minerals. Clementine data suggested there was ice in a permanently shadowed region of the Moon. The Lunar Prospector Mission focused on permanently shadowed craters to look deeper into the discovery and in 1998 found that the largest concentrations of hydrogen exist in the areas of the lunar surface that are never exposed to sunlight. The results indicated water ice at the lunar poles. However, the images were low resolution so no strong conclusions could be made.

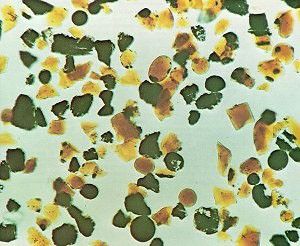

Revisiting Apollo Samples (2008)

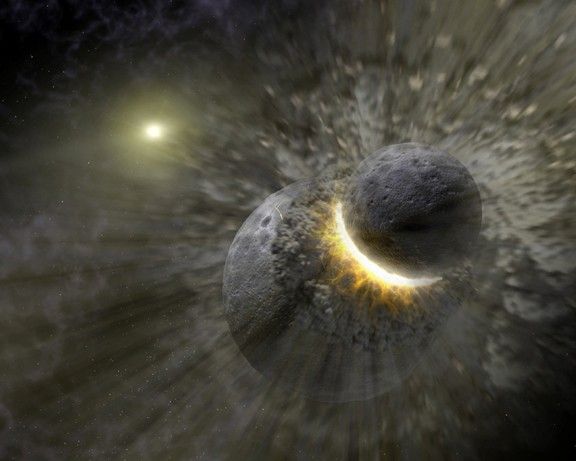

Capitalizing on major advances in technology since the Apollo era, researchers from Brown University revisited the Apollo samples. They found hydrogen inside tiny beads of volcanic glass. Since no volcanoes are erupting on the Moon today, the discovery presented evidence that water had existed in the Moon when the volcanoes erupted in the Moon’s ancient past. Additionally, the preserved hydrogen provided clues to the origins of lunar water: if it emerged from erupting volcanoes, it must have come from within the Moon. The discovery suggested that water was a part of the Moon since its early existence – and perhaps since it first formed.

Signs of Hydration (2009)

Chandrayaan, Cassini, Deep Impact

A suite of spacecraft enabled exciting discoveries in 2009. None were designed to look for water on the Moon, yet the Indian Space Research Organization’s Chandrayaan-1 and NASA’s Cassini and Deep Impact missions detected signs of hydrated minerals in the form of oxygen and hydrogen molecules in sunlit areas of the Moon. Researchers couldn’t determine whether they were seeing hydration by hydroxyl (OH) or water (H2O). They also debated whether the amount of hydration depended on the time of day.

Observations of Lunar Debris Reveal More (2009 – 2019)

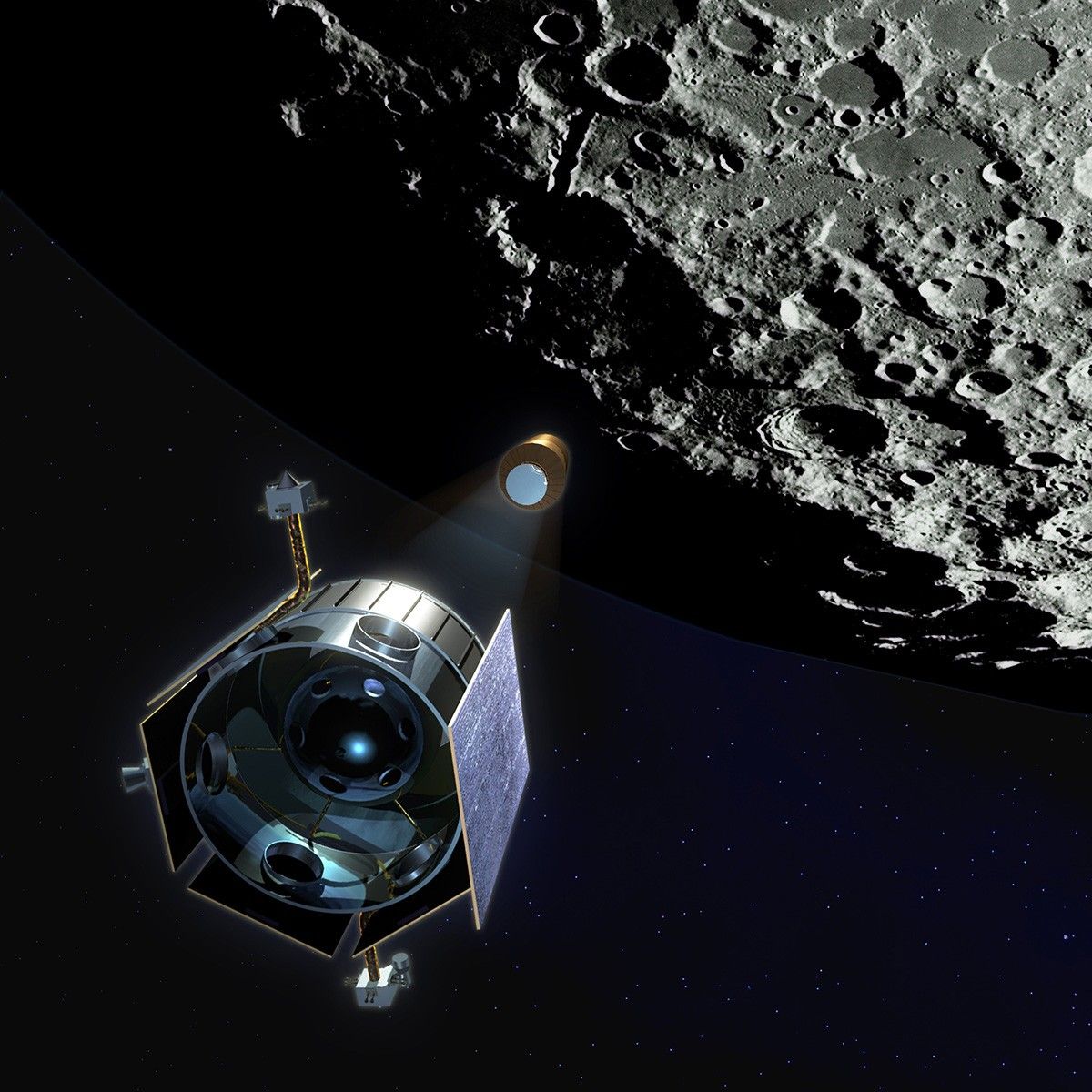

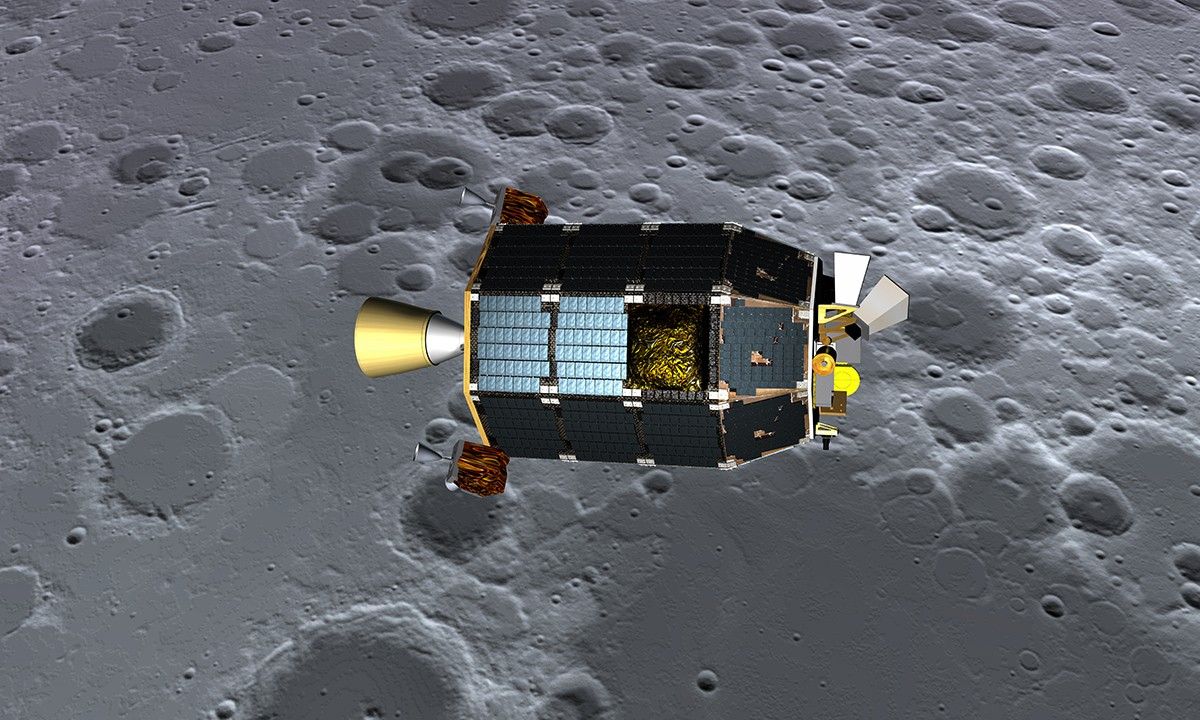

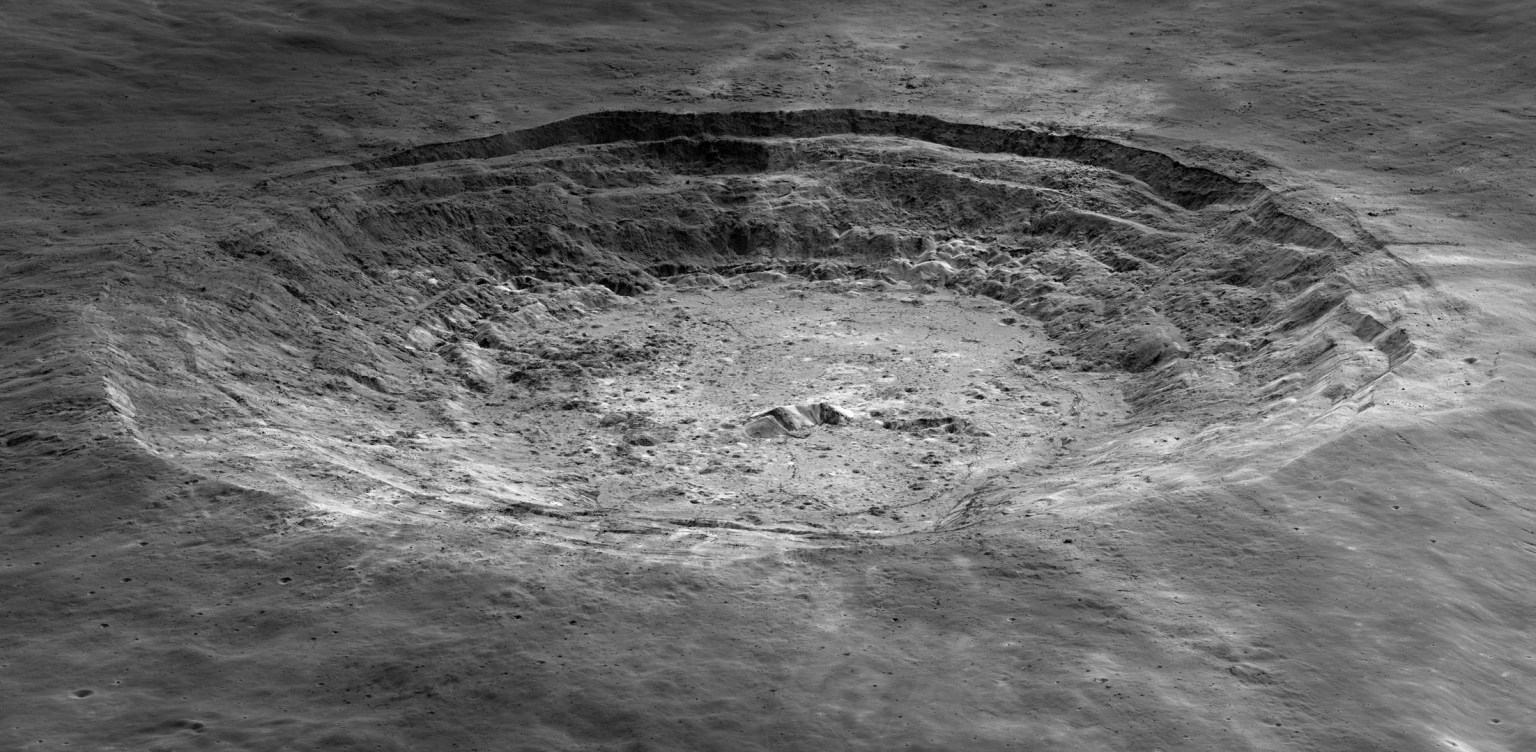

The Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) spacecraft and Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) launched together in 2009. Later that year, LCROSS intentionally discharged a projectile into a crater believed to contain water ice, and flew through the debris from the projectile’s impact. Four minutes later, LCROSS itself intentionally impacted the Moon while LRO observed. The combined observations showed grains of water ice in the ejected material. The LRO and LCROSS findings added to a growing body of evidence that water exists on the Moon in the form of ice within permanently shadowed regions. LRO continues to orbit the Moon and provide data used to characterize and map lunar resources, including hydrogen.

Confirmation of Moon Water – Shadowed Regions (2018)

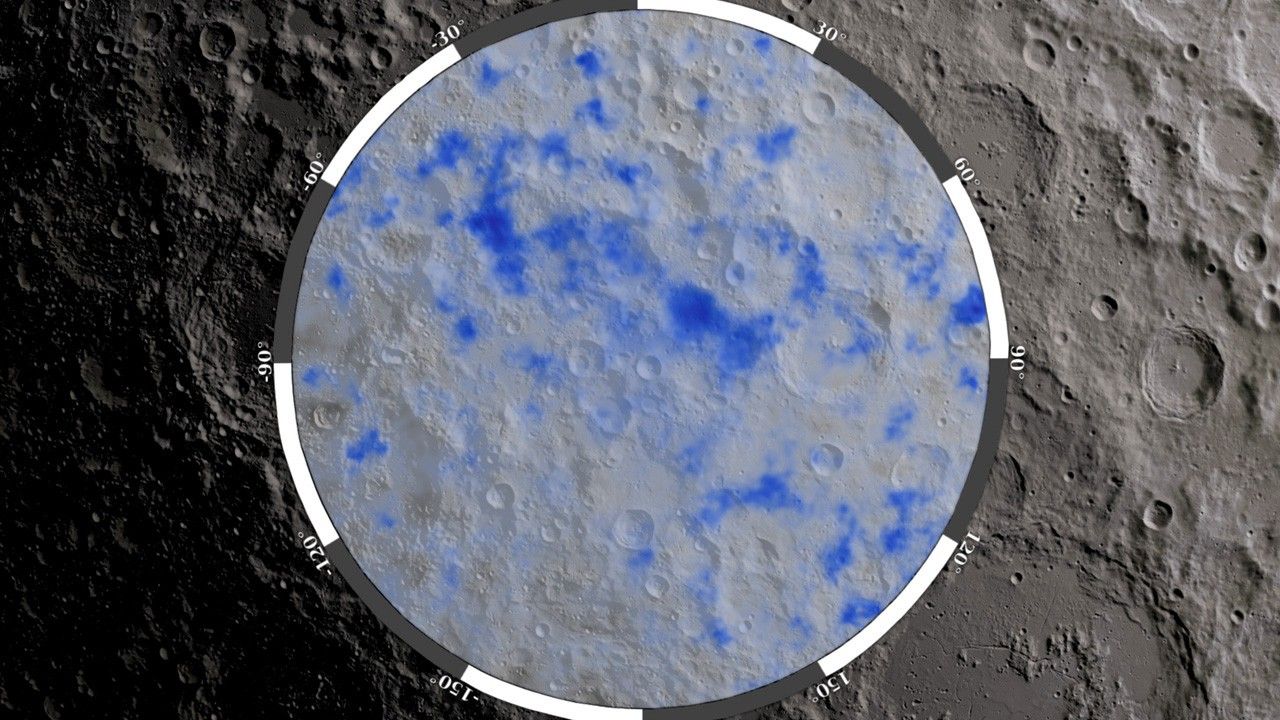

Data from Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3), carried by ISRO's Chandrayaan-1, provided scientists with the first high-resolution map of the minerals that make up the lunar surface. The NASA instrument flew aboard India’s Chandrayaan-1 mission in 2009. An analysis of the full set of data from M3, announced in 2018, revealed multiple confirmed locations of water ice in permanently shadowed regions of the Moon.

Confirmation of Moon Water – Sunlit Surface (2020)

In 2020, NASA announced the discovery of water on the sunlit surface of the Moon. Data from the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), revealed that in Clavius crater, water exists in concentrations roughly equivalent to a 12-ounce bottle of water within a cubic meter of soil across the lunar surface. The discovery showed that water could be distributed across the lunar surface, even on sunlit portions, and not confined to cold, dark areas.

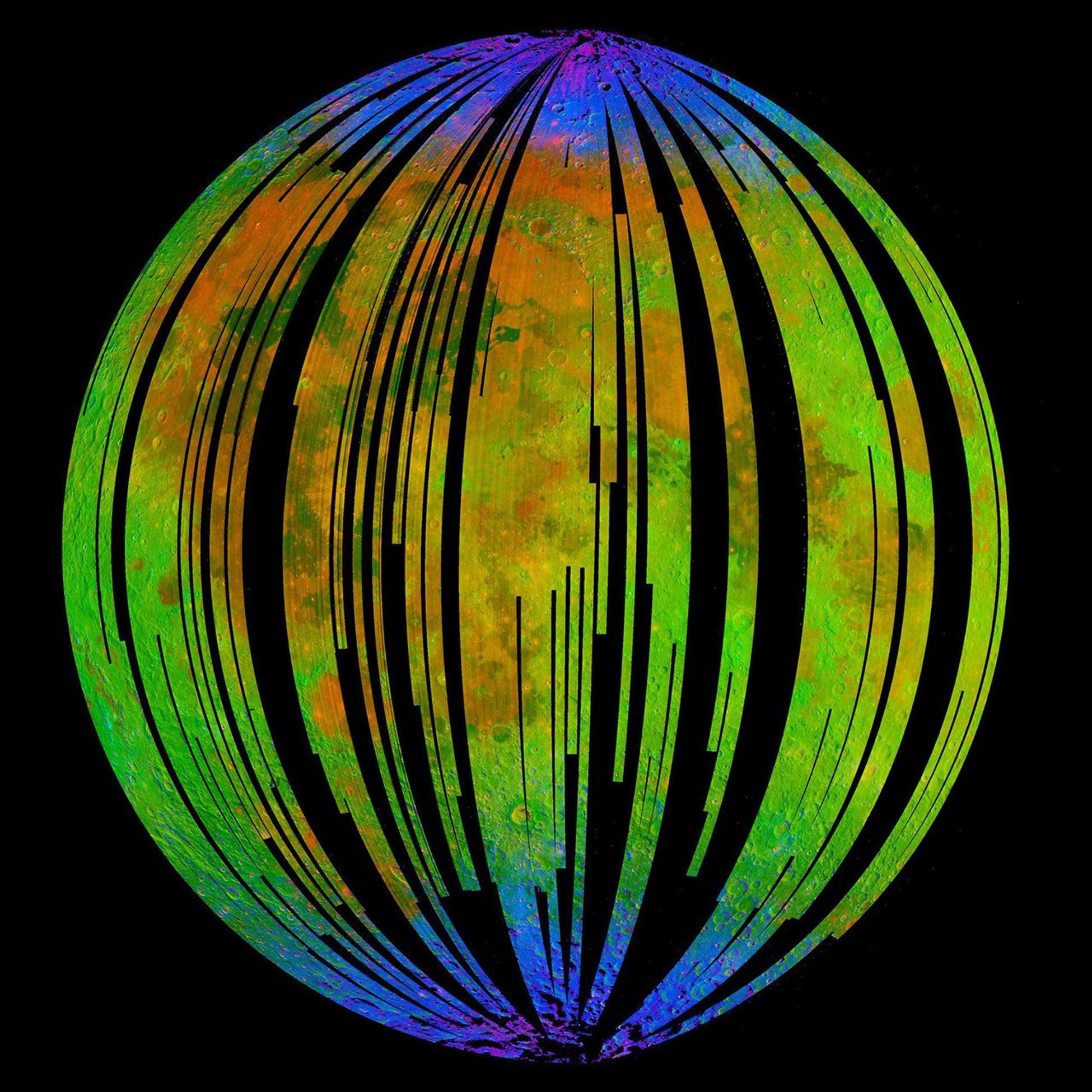

First Detailed, Wide-Area Map of Water on the Moon (2023)

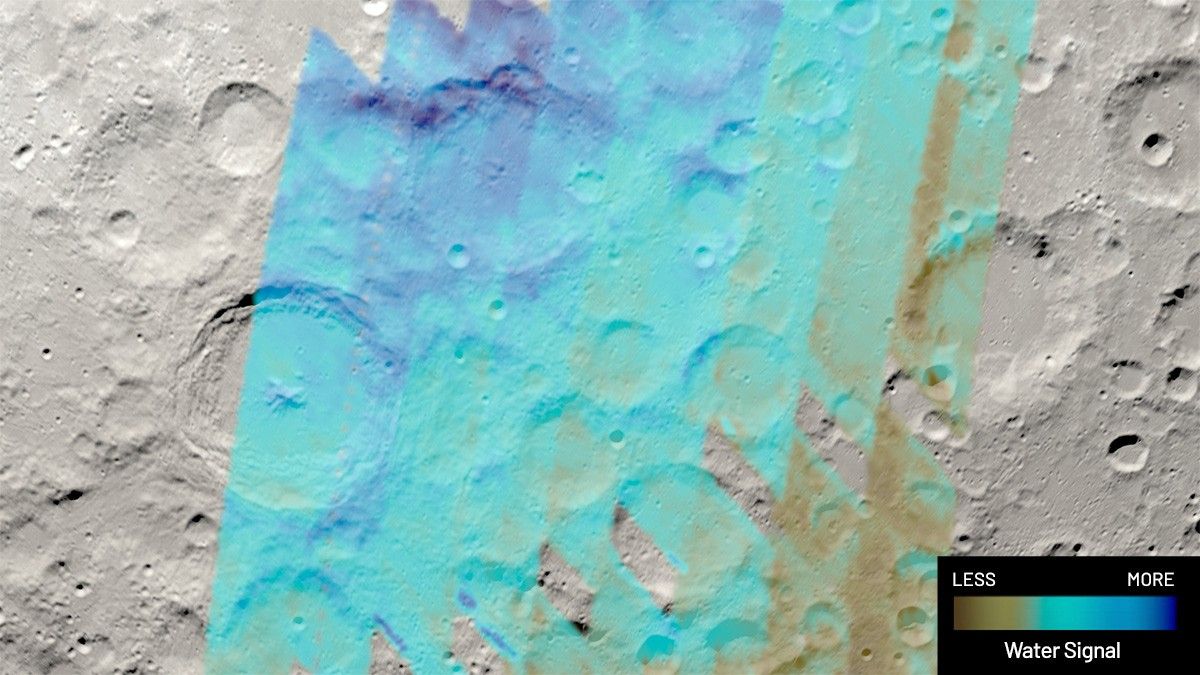

In 2023, a new map of water distribution on the Moon provided hints about how water may be moving across the Moon’s surface. The map, made using SOFIA data, extends to the Moon’s South Pole – the intended region of study for NASA’s Artemis missions, and the water-hunting rover, VIPER.

More to Discover

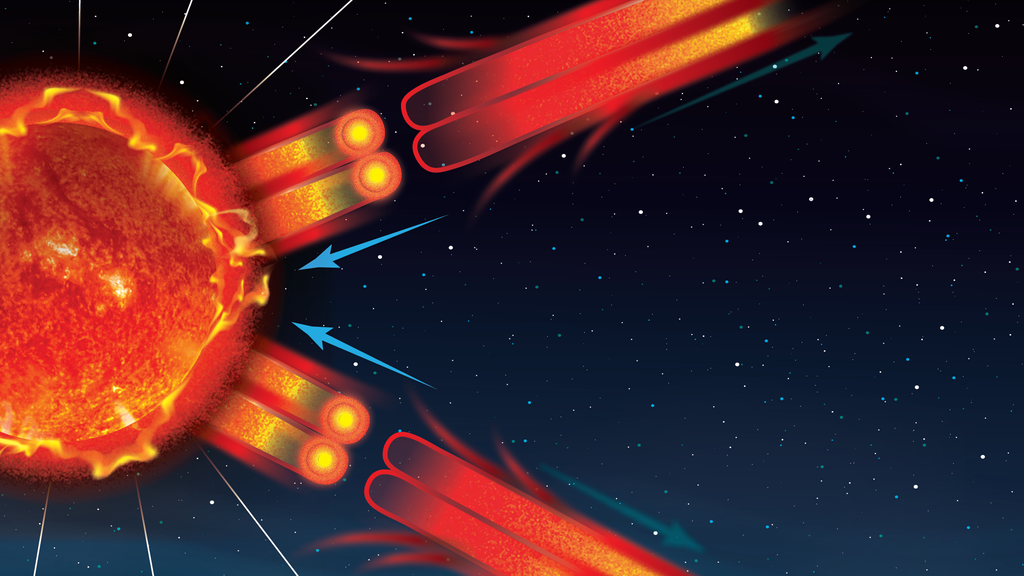

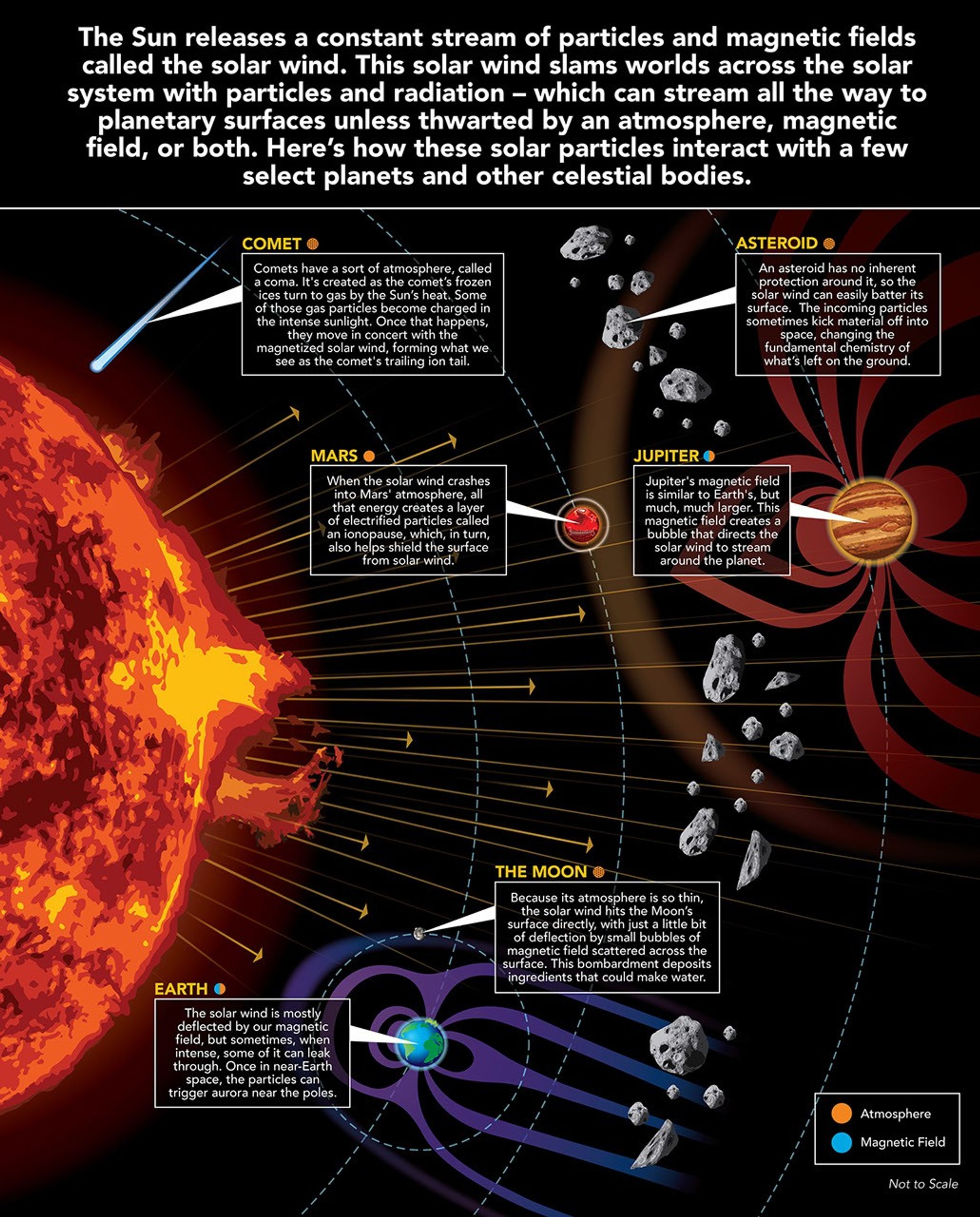

Researchers have confirmed that water exists both in the sunlit and shadowed surfaces of the Moon, yet many questions remain. Lunar scientists continue to investigate the origins of water and its behavior. There is evidence that the water on the Moon comes from ancient and current comet impacts, icy micrometeorites colliding on the lunar surface, and lunar dust interactions with the solar wind. However, more research is needed to understand the full history, present, and future of water on the Moon.

Writer: Allison Gasparini and Molly Wasser

Science Advisors: Casey Honniball, Tim Livengood, NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center