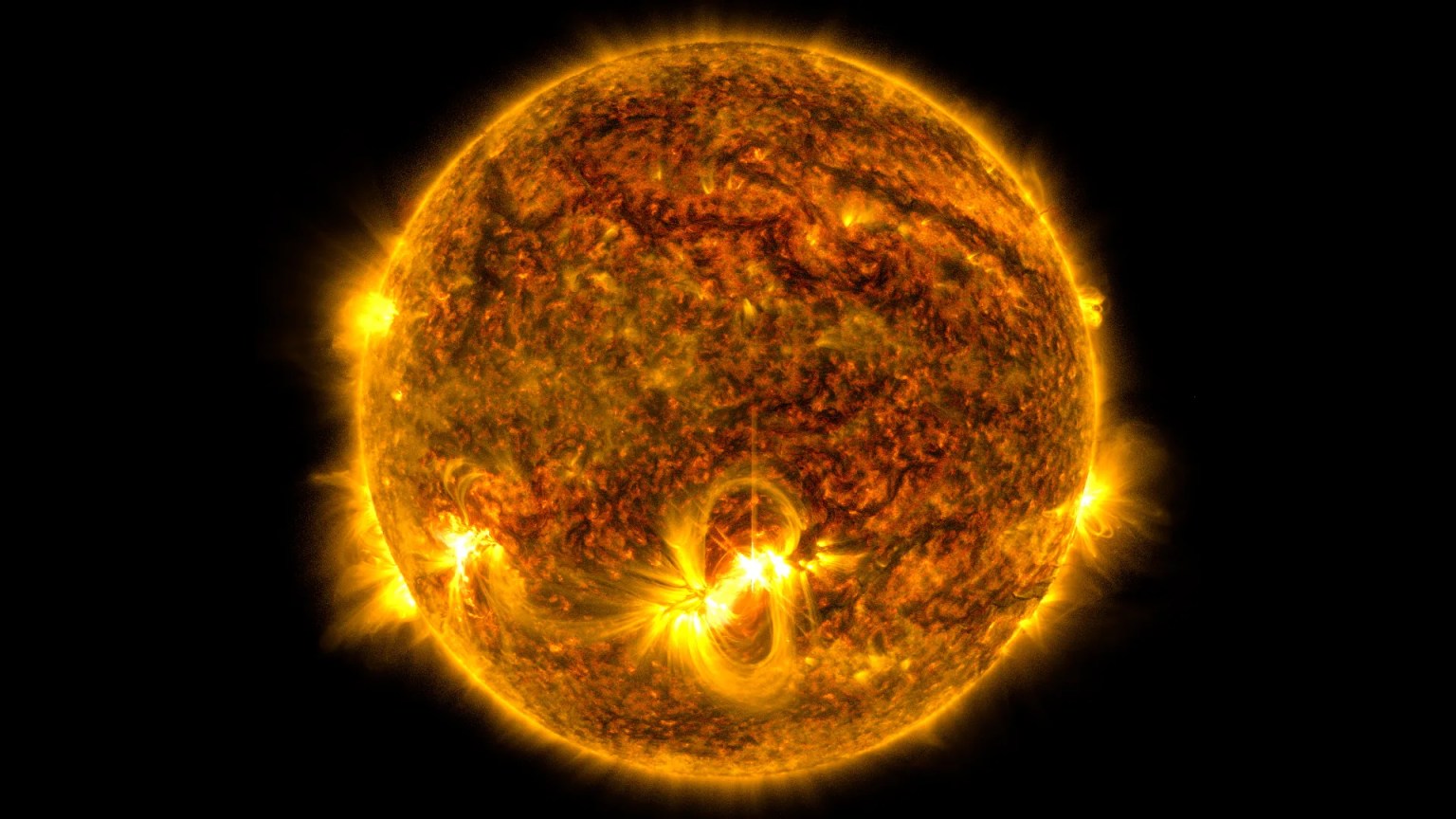

Here’s the deal — here at NASA we share all kinds of amazing images of planets, stars, galaxies, astronauts, other humans, and such, but those photos can only capture part of what’s out there. Every image only shows ordinary matter (scientists sometimes call it baryonic matter), which is stuff made from protons, neutrons, and electrons. The problem astronomers have is that most of the matter in the universe is not ordinary matter – it’s a mysterious substance called dark matter.

What is dark matter? We don’t really know. That’s not to say we don’t know anything about it – we can see its effects on ordinary matter. We’ve been getting clues about what it is and what it is not for decades. However, it’s hard to pinpoint its exact nature when it doesn’t emit light our telescopes can see.

Misbehaving galaxies

The first hint that we might be missing something came in the 1930s when astronomers noticed that the visible matter in some clusters of galaxies wasn’t enough to hold the cluster together. The galaxies were moving so fast that they should have gone zinging out of the cluster before too long (astronomically speaking), leaving no cluster behind.

It turns out, there’s a similar problem with individual galaxies. In the 1960s and 70s, astronomers mapped out how fast the stars in a galaxy were moving relative to its center. The outer parts of every single spiral galaxy the scientists looked at were traveling so fast that they should have been flying apart.

Something was missing – a lot of it! In order to explain how galaxies moved in clusters and stars moved in individual galaxies, they needed more matter than scientists could see. And not just a little more matter. A lot … a lot, a lot. Astronomers call this missing mass “dark matter” — “dark” because we don’t know what it is. There would need to be five times as much dark matter as ordinary matter to solve the problem.

Holding things together

Dark matter keeps galaxies and galaxy clusters from coming apart at the seams, which means dark matter experiences gravity the same way we do.

In addition to holding things together, it distorts space like any other mass. Sometimes we see distant galaxies whose light has been bent around massive objects on its way to us. This makes the galaxies appear stretched out or contorted. These distortions provide another measurement of dark matter.

Undiscovered particles?

There have been a number of theories over the past several decades about what dark matter could be; for example, could dark matter be black holes and neutron stars – dead stars that aren’t shining anymore? However, most of the theories have been disproven. Currently, a leading class of candidates involves an as-yet-undiscovered type of elementary particle called WIMPs, or Weakly Interacting Massive Particles.

Theorists have envisioned a range of WIMP types and what happens when they collide with each other. Two possibilities are that the WIMPS could mutually annihilate, or they could produce an intermediate, quickly decaying particle. In both cases, the collision would end with the production of gamma rays — the most energetic form of light — within the detection range of our Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

Tantalizing evidence close to home

In 2014, researchers took a look at Fermi data from near the center of our galaxy and subtracted out the gamma rays produced by known sources. There was a left-over gamma-ray signal, which could be consistent with some forms of dark matter.

While it was an exciting finding, the case is not yet closed because lots of things at the center of the galaxy make gamma rays. It’s going to take multiple sightings using other experiments and looking at other astronomical objects to know for sure if this excess is from dark matter.

In the meantime, Fermi will continue the search.