by Pat Brennan,

NASA's Exoplanet Exploration Program

First they rolled in one by one, those newly discovered planets, like billiard balls pushed across a table.

Counting them was easy.

Then they came in handfuls. Still quite manageable; as ground-based observatories began to pile up their discoveries of exoplanets – planets around other stars – in the 1990s and early 2000s, astronomers had no trouble keeping a running tally.

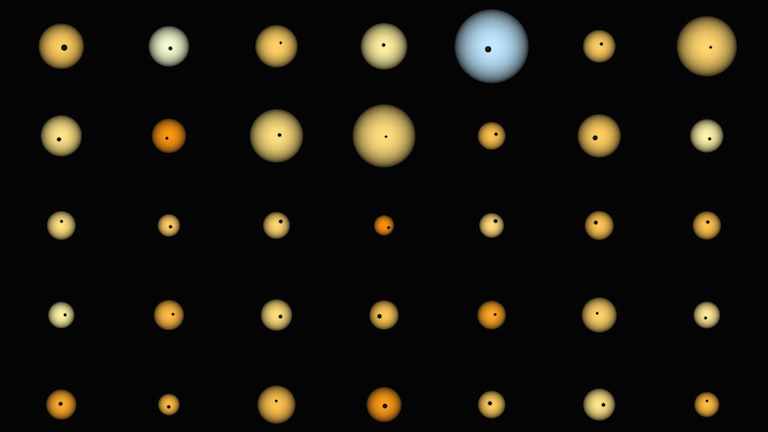

But when discoveries of exoplanets began to flow from space-based telescopes, it was like a pool shark making a big, smashing break. The billiard balls raced across the table in bunches. In just a few years, scientists were racking up new planets by the thousands.

And it wasn’t just the number, but the types of planets that had to be accounted for. Hot Jupiters, gas giants, rocky, Earth-sized worlds, “super Earths”; hints of potentially frozen, scalding, lava-choked, icy, steamy or watery planets.

Dashboard upgrade

NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute, keepers of the NASA Exoplanet Archive, set up automated counters of exoplanet discoveries – running, online dashboards tracking the number and variety. The latest totals: some 3,700 confirmed exoplanets in our galaxy, with thousands more candidate planets that remain unconfirmed.

But now, after piling up two decades worth of exoplanet discoveries, NASA scientists have begun a wholesale reshuffling of their counting methods.

At first, this means a drop in the number of “candidate” planets, with roughly half moving to the “confirmed” category. These planets were already confirmed but were being double counted: The previous number on the counter, 4,496, was labeled “candidates,” but critically, it included the combined total of confirmed and unconfirmed exoplanets, and only from NASA’s Kepler space telescope observations from 2009 to 2013.

In the new counter, only “unconfirmed” planets are labeled as “candidates.” The count also pulls in other NASA mission discoveries, including Kepler’s more recent observations and future exoplanet finds.

That means the initial candidate total drops to 2,724.

We’re going to need a bigger counter

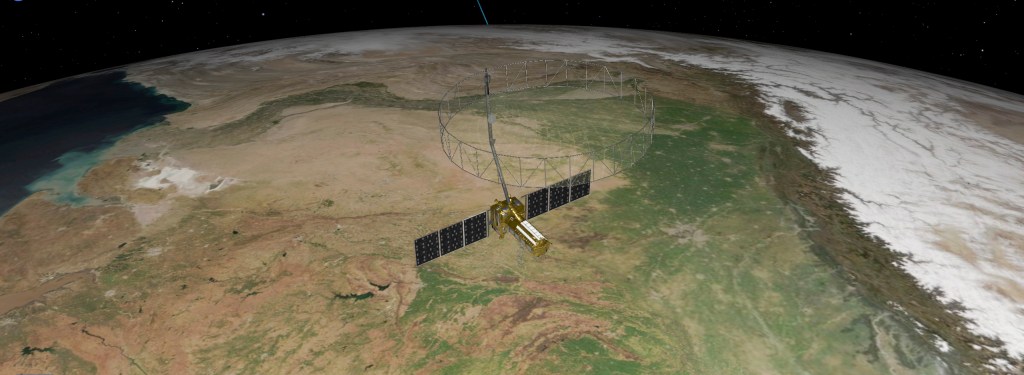

But the drop in candidates is temporary. Once the next torrent is unleashed – exoplanet discoveries from the just-launched Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), likely to begin to flow in early 2019 – planetary candidates are expected to soar into the tens of thousands.

“There could be over 10,000 candidates within the first couple of years,” said Eric Mamajek, the deputy program chief scientist for NASA’s Exoplanet Exploration Program. “Hundreds will be smaller than Neptune – dozens of things smaller than two or three (times Earth’s diameter), within the habitable zone of mostly M-dwarfs (red dwarf stars). There are also going to be thousands upon thousands of Jupiters detected around faint stars. All will initially be unconfirmed, but (some) will need further analysis and observation to follow up.”

And that could be just the beginning. In a kind of echo of “Moore’s law,” the rough doubling of computer processing power each year, Mamajek points out that exoplanet discoveries have doubled roughly every two years over the past three decades. The trend should continue over the next 10 years with data from TESS and future missions, such as the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST). That should keep the planet counter clicking.

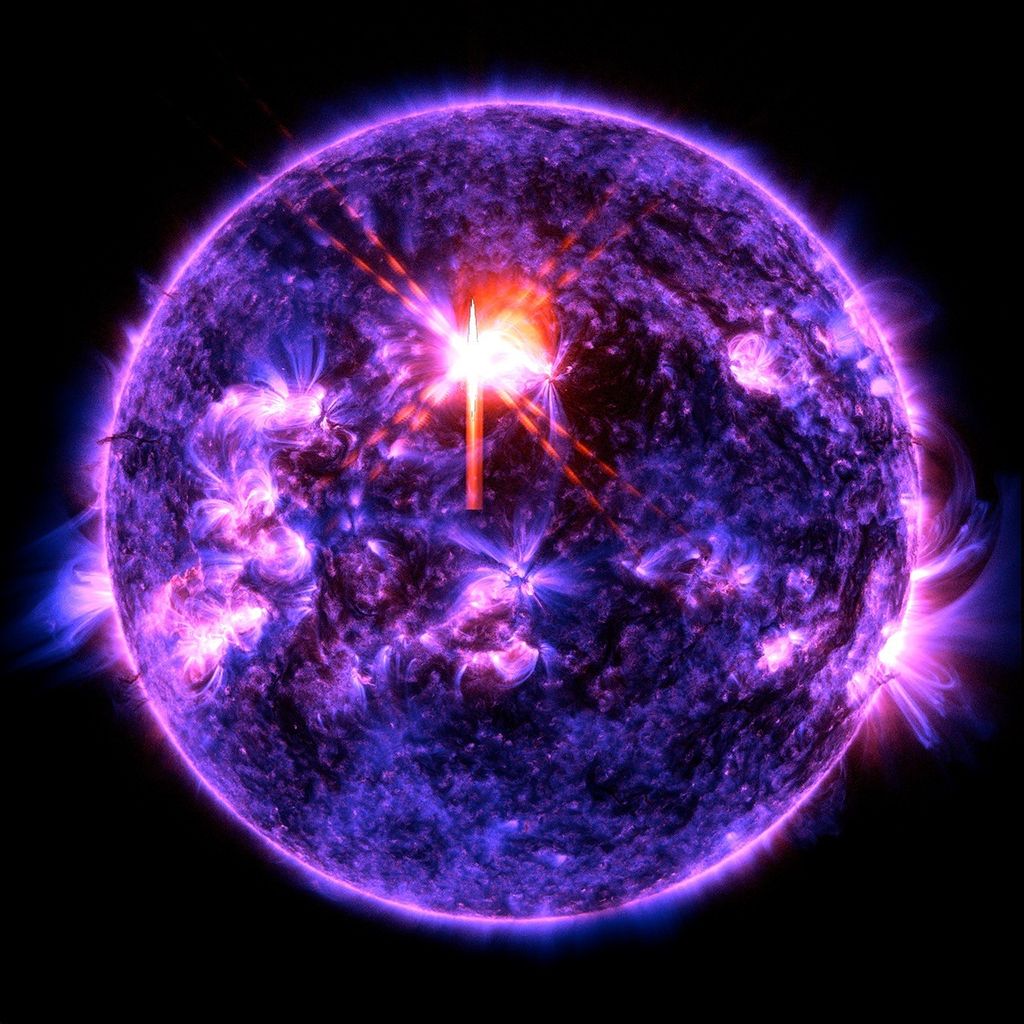

Other changes reveal the evolving nature of exoplanet science. During the first Kepler mission, the space telescope stared at a patch of sky for four years, watching more than 150,000 stars. For many of those stars, the telescope’s extremely sensitive detectors picked up tiny dips in starlight – the shadow of an orbiting planet passing in front of its star.

Scientists analyzed these dips and published papers, announcing raft after raft of exoplanet candidates and pushing them into the thousands. Follow-up observations and analytical techniques allowed large numbers of these candidates to be confirmed – to make sure they weren’t due to statistical noise or, perhaps, a companion star in a double-star system, masquerading as a planet.

“There’s always more work that needs to be done to confirm them,” Mamajek said. “They don’t come with a big stamp on their head that says, ‘planet.’”

All hands on deck for TESS

Planets from Kepler’s later observations also must be confirmed. These came after the failure of stabilizing components on the Kepler spacecraft ended its initial four-year stare. Clever engineers found a way to use the pressure of sunlight to stabilize the spacecraft, though its observation periods are now much shorter, about 80 days apiece.

But Kepler’s latest discoveries are confirmed using a different approach. The imaging data goes straight out to the astronomical community, rather than first being filtered through a scientific team. Candidate and confirmed planets are then published by the community at large.

TESS, a mission led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, will combine the two approaches.

“TESS will provide an official list of candidates,” said David Ciardi, a research astronomer and the chief scientist for NASA’s Exoplanet Science Institute at Caltech. “Then a bunch of candidates, the community will also provide. It is going to be super exciting!”

Precision counting and a bigger pool of astronomers: It’s all to make sure that, amid a coming avalanche of exoplanet discoveries, planet counters don’t get left behind the eight ball.