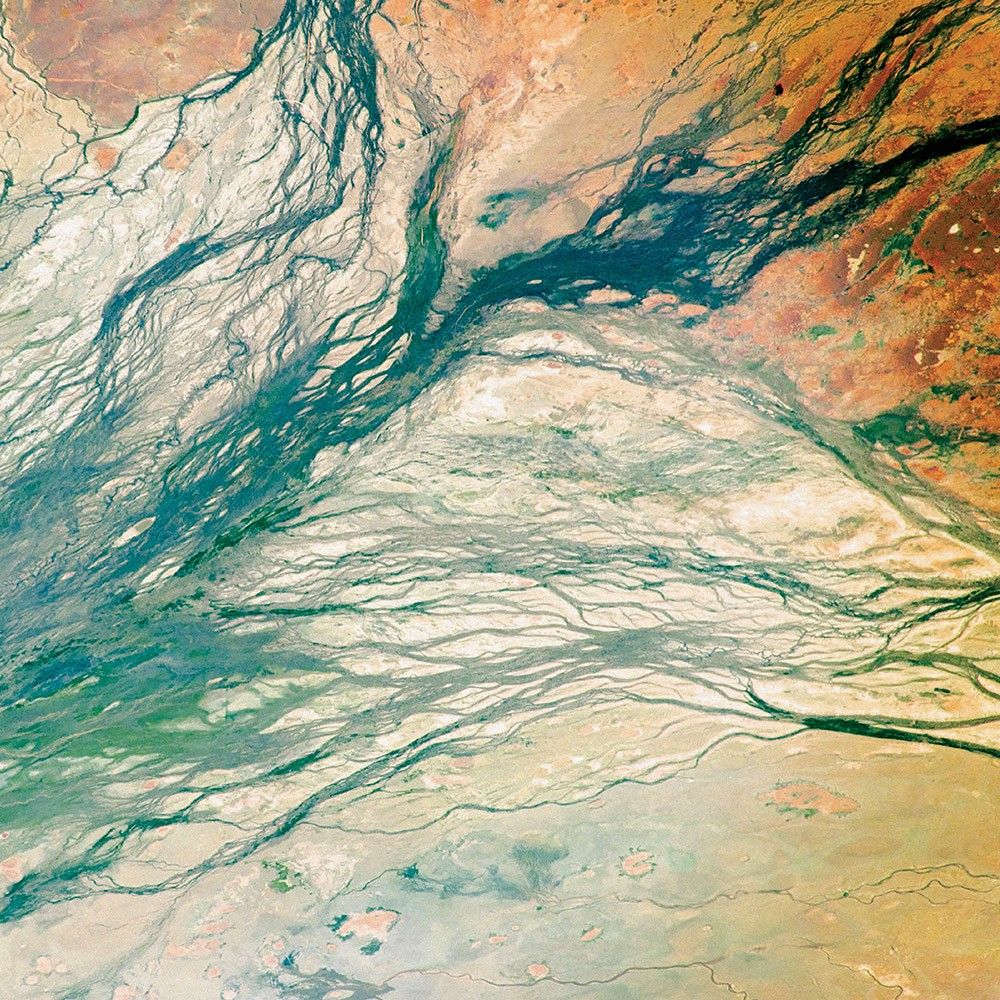

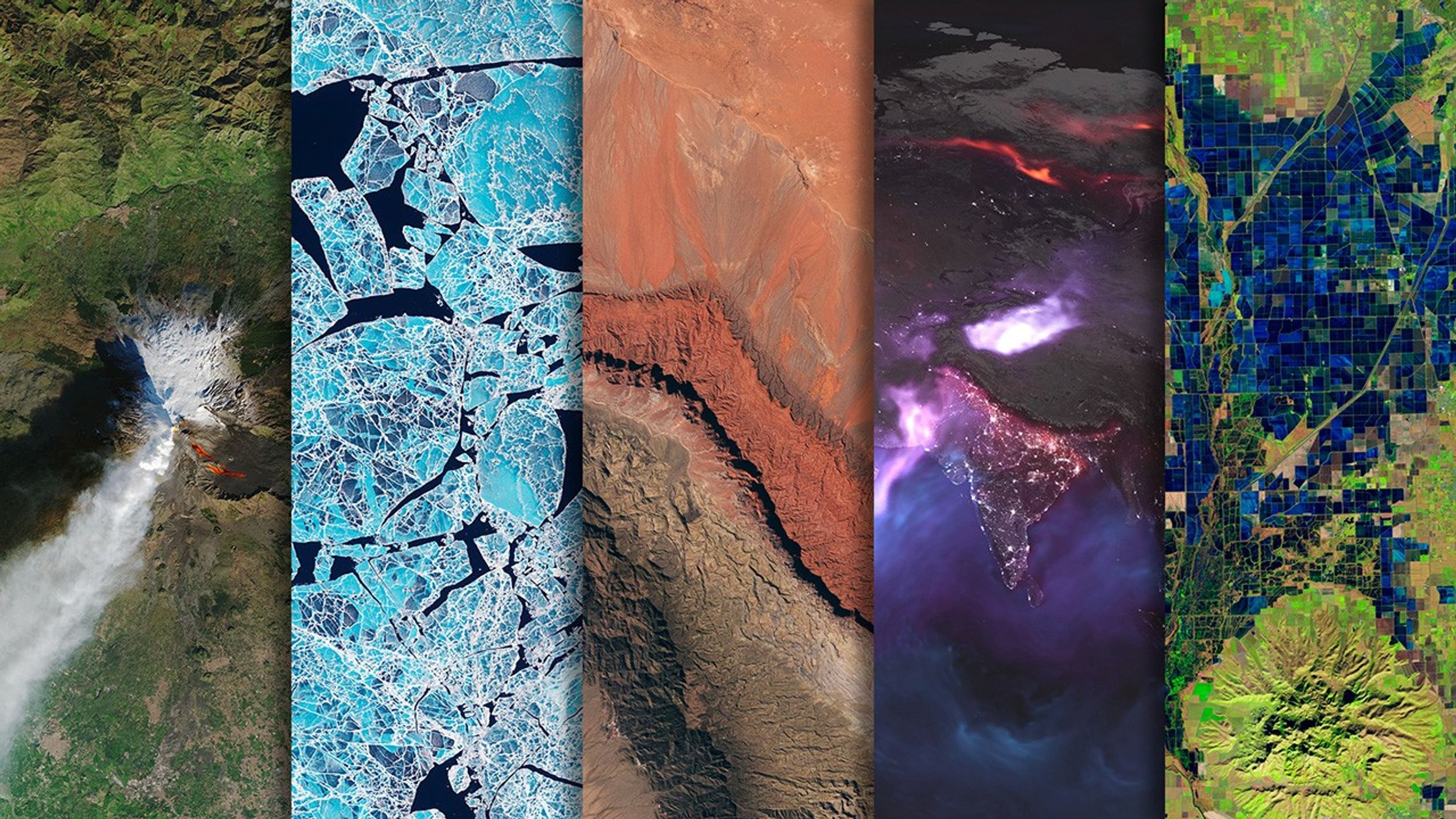

Channel Country

-

Australia

Australia’s Channel Country is full of hundreds of channels, as the Georgina, Burke, and Hamilton rivers merge into the very broad floodplain of Eyre Creek. The land is flat and the drainage is poor, which encourages semi-permanent wetlands to form at the meeting points of the rivers.

These wide floodplains in Queensland are unique on the planet. Scientists think they are caused by the extreme variation in water and sediment discharges from the rivers. In many years there is no rainfall at all, and the rivers are effectively non-existent. In years of modest rainfall, the main channels will carry some water, sometimes spilling over into narrow water holes known as billabongs.

Every few decades, the floodplain carries extremely high discharges of water. For instance, tropical storms to the north can lead to great water flows that inundate the entire width of the floodplain. On such occasions, the floodplain appears as series of brown and green water surfaces with only tree tops indicating the location of the islands. Such is the case in this image taken from the International Space Station in September 2016.

Tea-Colored Rupert Bay

-

Canada

Remote Rupert Bay is a place where the majesty and dynamism of fluid dynamics is regularly on display. With several rivers pouring into this nook of James Bay, the collision of river and sea water combines with the churn of tides and the motion of currents to make swirls of colorful fluid.

As they wind through the boreal forests and wetlands of northern Quebec, the rivers that flow into Rupert Bay carry water stained brown with natural chemical substances found in plants. Tannins and lignins from roots, leaves, seeds, bark, and soil can leach into the water and give it a yellow, brown, or even black color. (The same process gives tea its dark color.) Note that the colored plumes and intricate vortices around the islands are pointing inland—an indicator that the tide was likely coming in, or that northwesterly winds were affecting the flow of the water.

Coral Cocos

-

Indian Ocean

Coral atolls—which are largely composed of huge colonies of tiny animals such as cnidaria—form around islands. After the islands sink, the coral remains, generally forming complete or partial rings. The South Keeling Islands, part of the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean, are such a place.

Only some parts of the South Keeling Islands still stand above the water surface. In the north, the ocean overtops the coral. Along the southern rim of this atoll, shallow water appears aquamarine. Water darkens to navy blue as it deepens toward the central lagoon. Above the water line, coconut palms and other plants form a thick carpet of vegetation. Hard and soft corals thrive throughout the reef.

Bay of Whales

-

Russia

The area around Russia’s Ulbanskiy Bay is mostly uninhabited by humans, but it does support sizable numbers of whales. In summertime, this bay is a feeding ground for bowheads, belugas, and orcas that come to Ulbanskiy for the seafood buffet. They hunt by driving fish like herring and smelt toward the coast and into freshwater inlets.

Onshore, freshwater streams meander into marshlands and gently sloped mud flats. The marshes around the bay are dotted with small bodies of water. These are likely thermokarst lakes—pools of water that fill in depressions in the land surface as permafrost melts. Farther inland, the incline becomes steeper and the landscape darker with the greens of pine-covered slopes. A lighter green band (left side) indicates deciduous (leaf-shedding) trees that have begun to turn color.

Storms Stir Up Sediment

-

Bermuda

In October 2014, the eye of Hurricane Gonzalo passed right over Bermuda. In the process, the potent storm stirred up the sediments in the shallow bays and lagoons around the island, spreading a huge mass of sediment across the North Atlantic Ocean. This Landsat 8 image shows the area after Gonzalo passed through.

The suspended sediments were likely a combination of beach sand and carbonate sediments from around the shallows and reefs. Coral reefs can produce large amounts of calcium carbonate, which stays on the reef flats (where there are coralline algae that also produce carbonate) and builds up over time to form islands.

Storm-induced export of carbonates into the deep ocean—where they mostly dissolve—is one of the ways that the oceans naturally balance the addition of atmospheric carbon dioxide to ocean waters.

The Meeting of the Waters

-

Brazil

The Encontro das Águas, or the “Meeting of the Waters,” is one of those places that simply wow people.

As Robert Meade of the U.S. Geological Survey once described: “Six Mississippi Rivers’ worth of cafe-au-lait-colored water are converging here with two Mississippis’ worth of black-tea-colored water to produce the greatest hydrologic spectacle on the planet.”

The coffee-colored Rio Solimões, rich with sediment, runs down from the Andes Mountains. The black-tea-tinted Rio Negro that flows from the Colombian hills and jungles is nearly sediment-free and colored by decayed leaf and plant matter. Where the rivers meet, east of Manaus, Brazil, they flow side by side within the same channel for several kilometers. The cooler, denser, and faster waters of the Solimões and the warmer, slower waters of the Negro form a boundary that is visible from space. Turbulent eddies eventually mix the two and become the Lower Amazon River.

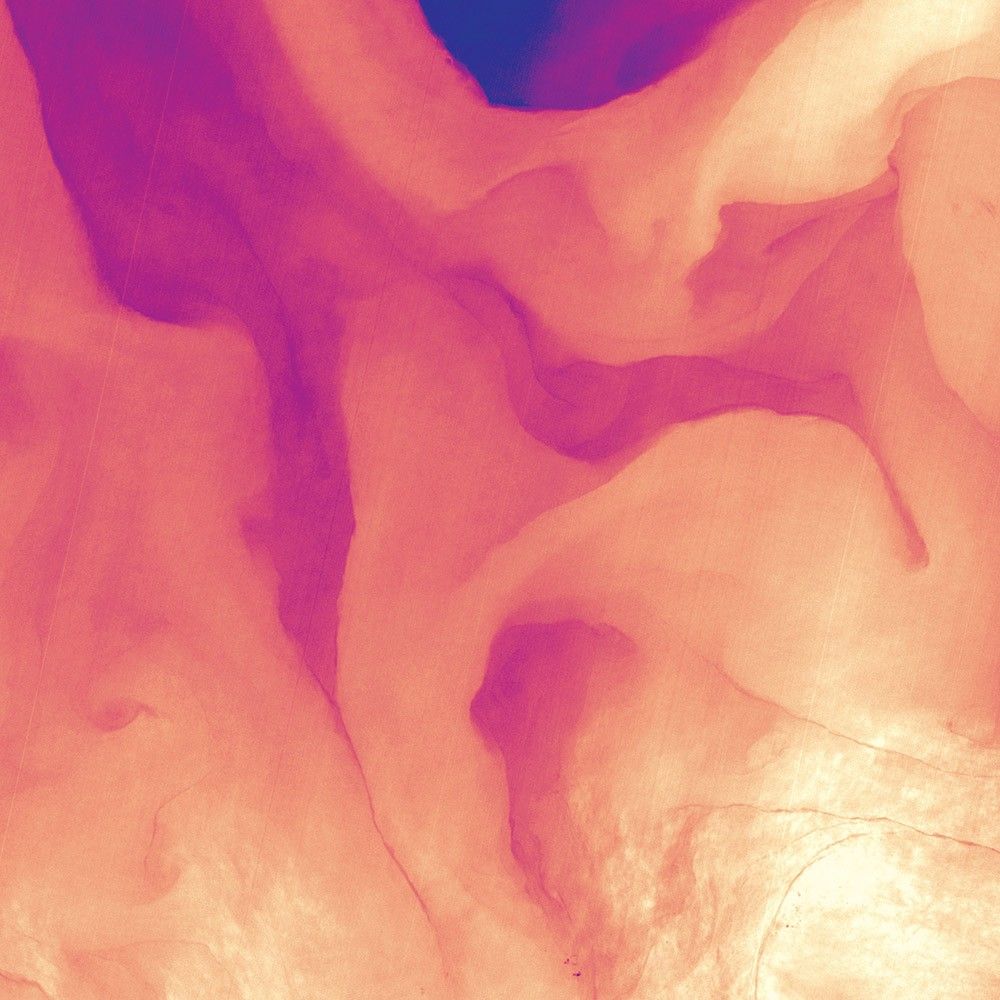

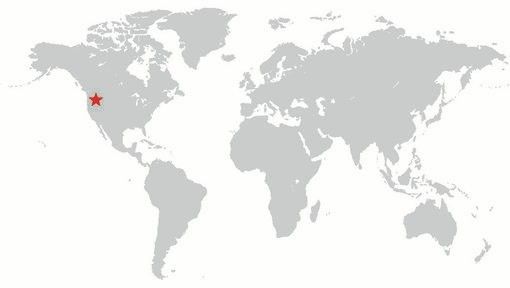

A Lava Lamp Look at the Atlantic

-

Atlantic Ocean

Stretching from tropical Florida to the doorstep of Europe, the Gulf Stream carries a lot of heat, salt, and history. This river of water is an important part of the global ocean conveyor belt, moving water and heat from the Equator toward the far North Atlantic. It is one of the strongest currents on Earth and one of the most studied. Its discovery is often attributed to Benjamin Franklin, though sailors likely knew about the current long before they had a name for it.

This image shows a small portion of the Gulf Stream off of South Carolina as it appeared in infrared data collected by the Landsat 8 satellite in April 2013. Colors represent the energy—heat—being emitted by the water, with cooler temperatures in purple and the warmest water being nearly white. Note how the Gulf Stream is not a uniform band but instead has finer streams and pockets of warmer and colder water.

Teeming Life in the Strait of Georgia

-

Canada

In August 2016, the waters off of British Columbia turned bright green. The Strait of Georgia and nearby inlets were teeming with coccolithophores—a harmless type of floating plant-like organisms called phytoplankton. Coccolithophores have chalky, scale-like shells made of calcium carbonate. The milky-white color of those shells can brighten and discolor otherwise blue waters when the plankton explode in such massive blooms.

While coccolithophore blooms occasionally occur off the west coast of Vancouver Island, few scientists could recall seeing a bloom like this in the strait. Research suggests that coccolithophore numbers have been increasing in recent decades even as the water has been growing more acidic.

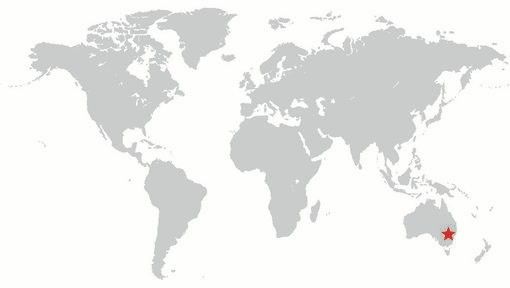

Ephemeral Lake Frome

-

Australia

The interior of Australia is full of ephemeral lakes. These basins pass most of their time as salt pans, but occasional heavy rains can fill them with water.

The Earth Observing-1 satellite captured this image in April 2010 after water had flowed into Lake Frome, which stands at the southern end of an arc of salt pans. When it fills, the waters usually come from precipitation in the hills and other salt pans upstream. The land to the east has a slightly higher elevation and consists of a network of dry river channels. Inside the salt pan, the land surface is uneven. Areas shaped like sloppy teardrops rise above the surrounding plain. Water on the surface appears in shades of dull green. And throughout much of Lake Frome, water makes its presence known not through standing water but through mud or wet salts. Darker surfaces show where water has seeped through typically dry sediments.

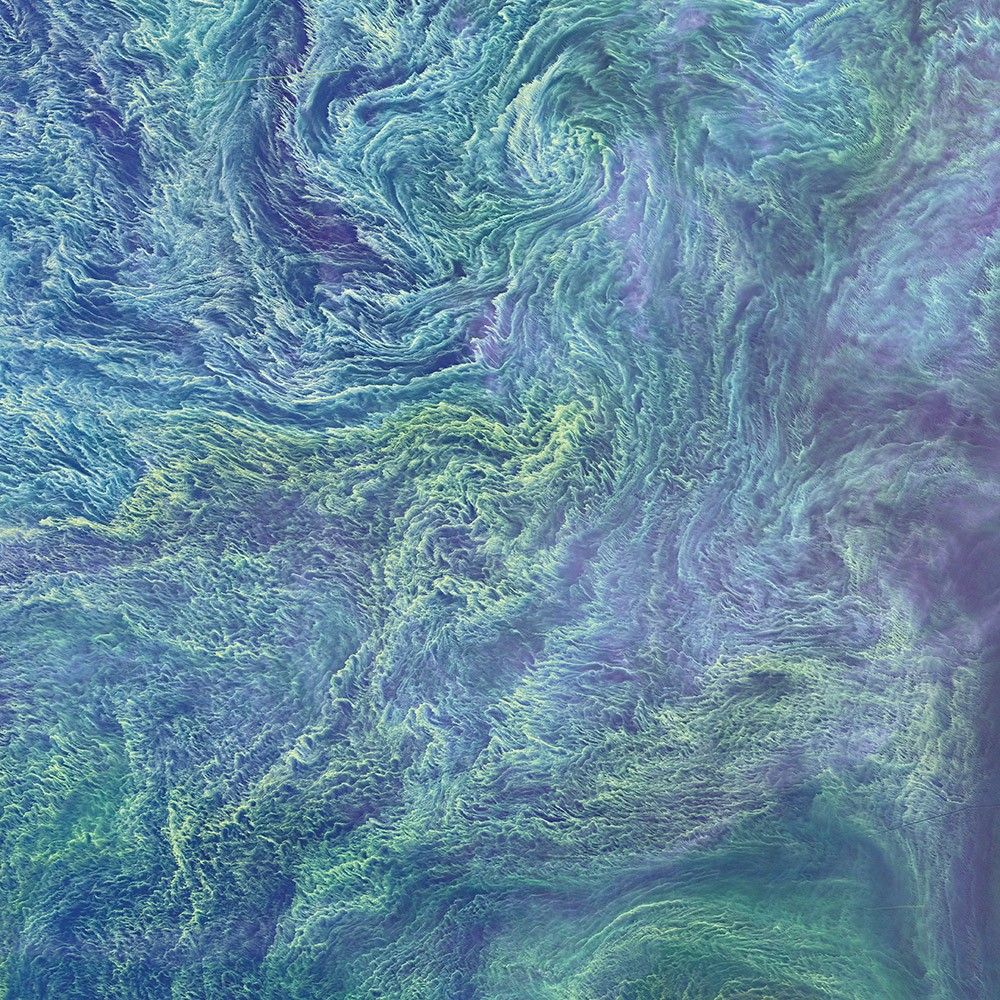

Dueling Blooms

-

Barents Sea

As the seasons pass on Earth, different species tend to dominate the landscape at different times. Such was the case in July 2014 in the surface waters of the Barents Sea, north of Norway and Russia. The Aqua satellite captured a transitional moment between one form of microscopic, plant-like organisms (phytoplankton) and another.

Several currents merge in this area, and intersecting waters combine with stiff winds to promote mixing of waters and nutrients from the deep. Note the green swirls on the center and left, as well as the milky, blue-white swirls on the upper right. (The fluffy white area is cloud cover.) It is likely that the green plankton were diatoms and the white ones were coccolithophores. Research has suggested that diatoms start to bloom in the well-mixed, cooler waters of spring and dominate the early summer. As the water warms and becomes more stratified or layered, coccolithophores bloom more abundantly.

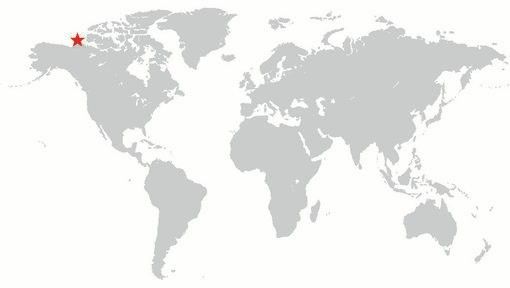

A Bay Sculpted by Ice

-

Canada

The land around Liverpool Bay in Canada’s Northwest Territories owes its otherworldly appearance to ice past and present.

Thousands of years ago, this area was buried under a massive ice sheet that sprawled over much of North America. During that time, glacial activity carved out parallel lakes separated by strips of land that look like giant, skeletal fingers. After the glaciers retreated, pockets of ice lingered underground. As those pockets have melted and the frozen ground has thawed, lakes have formed.

Geologists have offered different explanations for the formation of the finger-shaped ridges: they may be moraines created by the movement of ice, or they might be sediment ridges that formed between channels of subglacial meltwater. Smaller thermokarst lakes in this scene are formed by both the long- and short-term melting of ice and permafrost.

Tidal Flats and Channels

-

Bahamas

The islands of the Bahamas are situated on large depositional platforms—the Great and Little Bahama Banks—composed mainly of carbonate sediments ringed by reefs. The islands are the only parts of the platform currently exposed above sea level. The sediments were formed mostly from the skeletal remains of organisms settling to the sea floor; over geologic time, these sediments consolidated to form carbonate sedimentary rocks such as limestone.

This November 2010 photograph from the International Space Station provides a view of tidal flats and underwater channels along the eastern margin of the Great Bahama Bank. The continuously exposed parts of the islands are brown, a result of soil formation and vegetation growth. To the north and west, we can see through shallow water to the off-white tidal flats composed of carbonate sediments. The tidal flow of seawater is concentrated through gaps in the seafloor, leading to the formation of relatively deep channels that cut into the sediments.

The Blooming Baltic

-

Baltic Sea

Cyanobacteria are an ancient type of marine bacteria that, like other phytoplankton, capture and store solar energy through photosynthesis. Some cyanobacteria are toxic to humans and animals. Moreover, large blooms can sometimes cause oxygen-depleted dead zones where other organisms cannot survive.

In August 2015, Landsat 8 captured this false-color view of a large bloom of cyanobacteria swirling in the Baltic Sea. Blooms flourish here during summertime, when there is ample sunlight and high levels of nutrients. Tracks of several ships show up as dark lines where they have cut through the bloom.

Agricultural and industrial runoff from Europe can contribute to excess nutrients in the Baltic Sea. Nutrient loads have been decreasing since 1980, and coastal areas have seen improvement, yet concentrations in the open sea have not changed much.

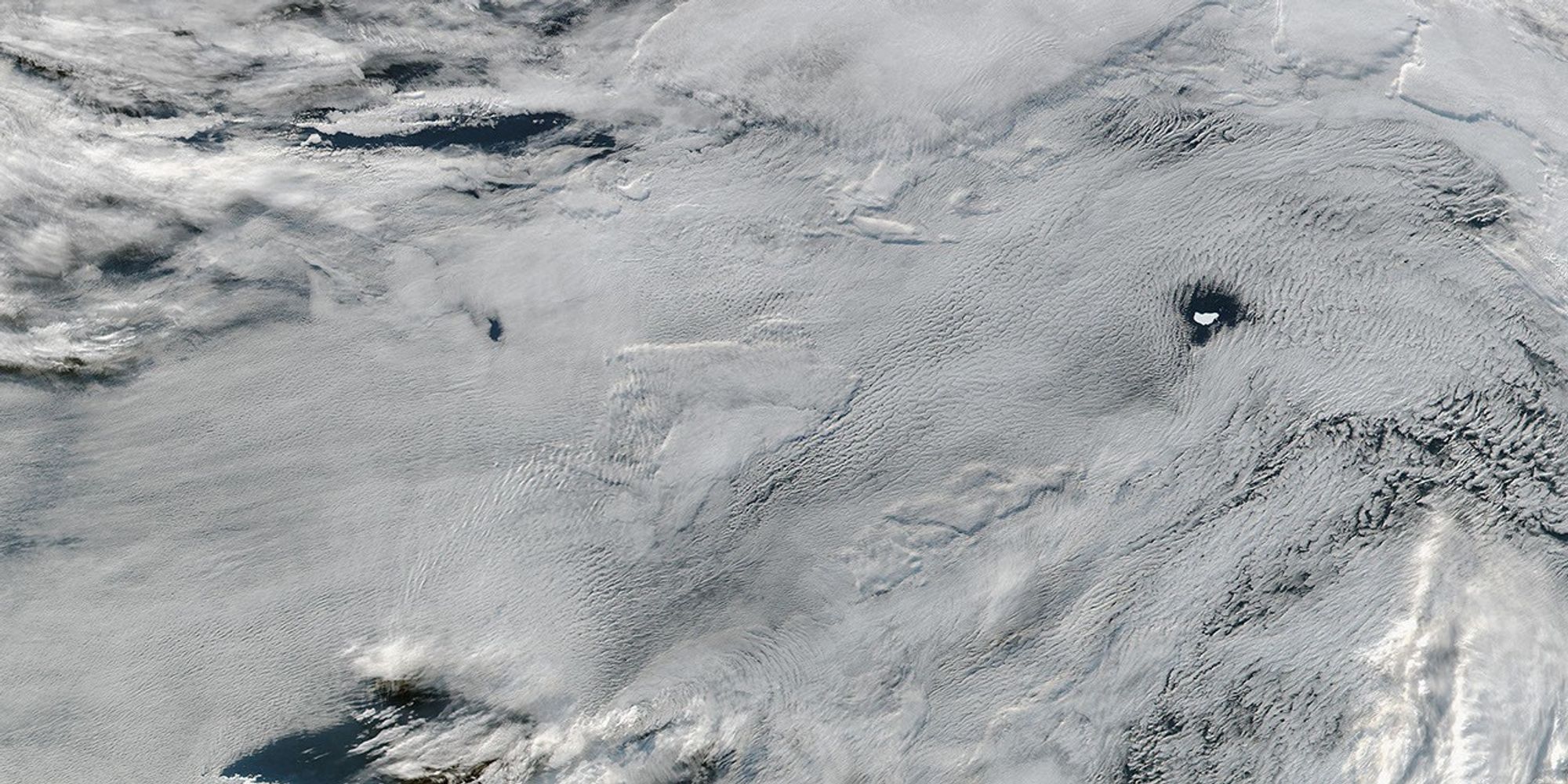

Waves Beneath the Waves

-

Trinidad

Internal waves are the surface manifestation of slow waves that move tens of meters beneath the sea surface. These waves beneath the waves produce enough of an effect on the sea surface to be visible from space when they are enhanced by the reflection of sunlight, or sunglint, back toward a camera.

This January 2013 photograph from the International Space Station shows at least three sets of internal waves interacting. The most prominent set (top left) shows several waves moving from the northwest due to the tidal flow toward the north coast of Trinidad. Two less prominent sets can be seen further out to sea. All of these internal waves are probably caused by the shelf break near Tobago. The shelf break is the step between shallow seas (around continents and islands) and the deep ocean. It is the line at which tides usually start to generate internal waves.

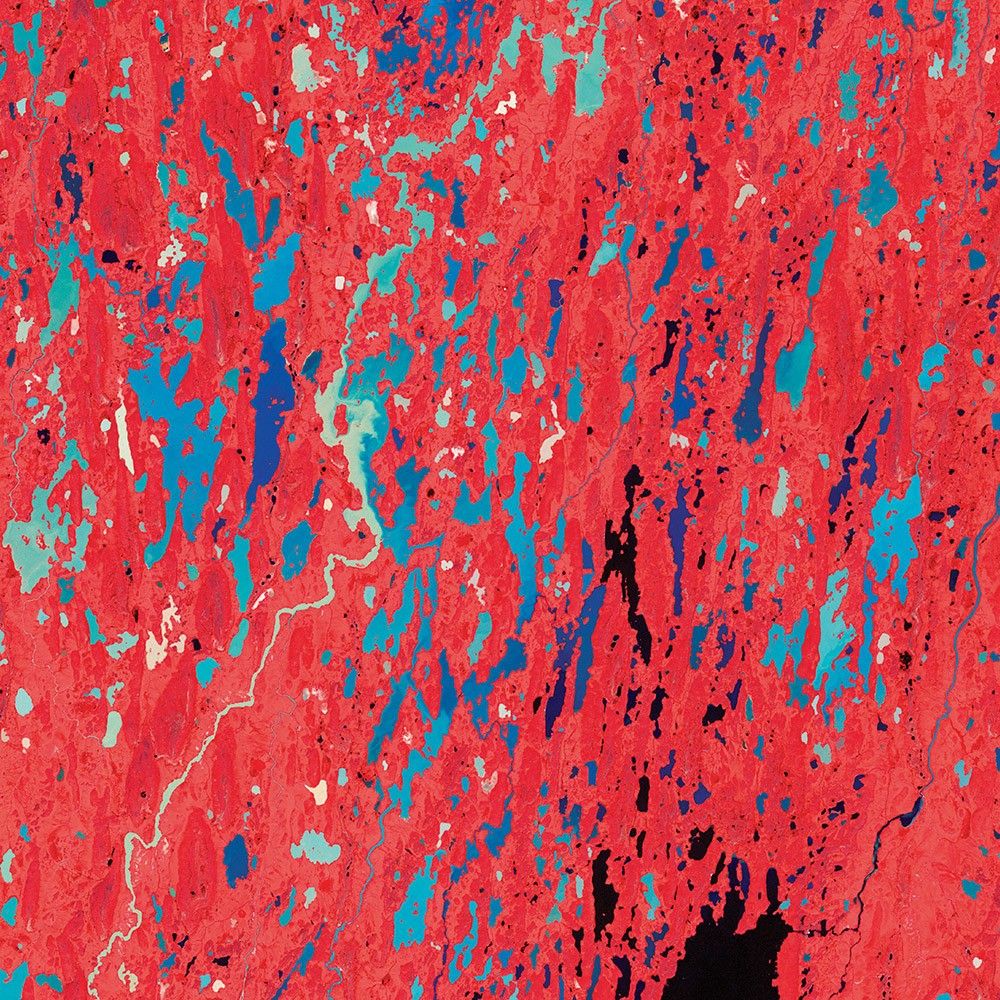

Land of Lakes

-

Canada

During the last Ice Age, nearly all of Canada was covered by a massive ice sheet. Thousands of years later, the landscape still shows the scars of that icy earth-mover. Surfaces that were scoured by retreating ice and flooded by Arctic seas are now dotted with millions of lakes, ponds, and streams. In this false-color view from the Terra satellite, water is various shades of blue, green, tan, and black, depending on the amount of suspended sediment and phytoplankton; vegetation is red.

The region of Nunavut Territory is sometimes referred to as the “Barren Grounds,” as it is nearly treeless and largely unsuitable for agriculture. The ground is snow-covered for much of the year, and the soil typically remains frozen (permafrost) even during the summer thaw. Nonetheless, this July 2001 image shows plenty of surface vegetation in midsummer, including lichens, mosses, shrubs, and grasses. The abundant fresh water also means the area is teeming with flies and mosquitoes.

Plankton and Sulfur

-

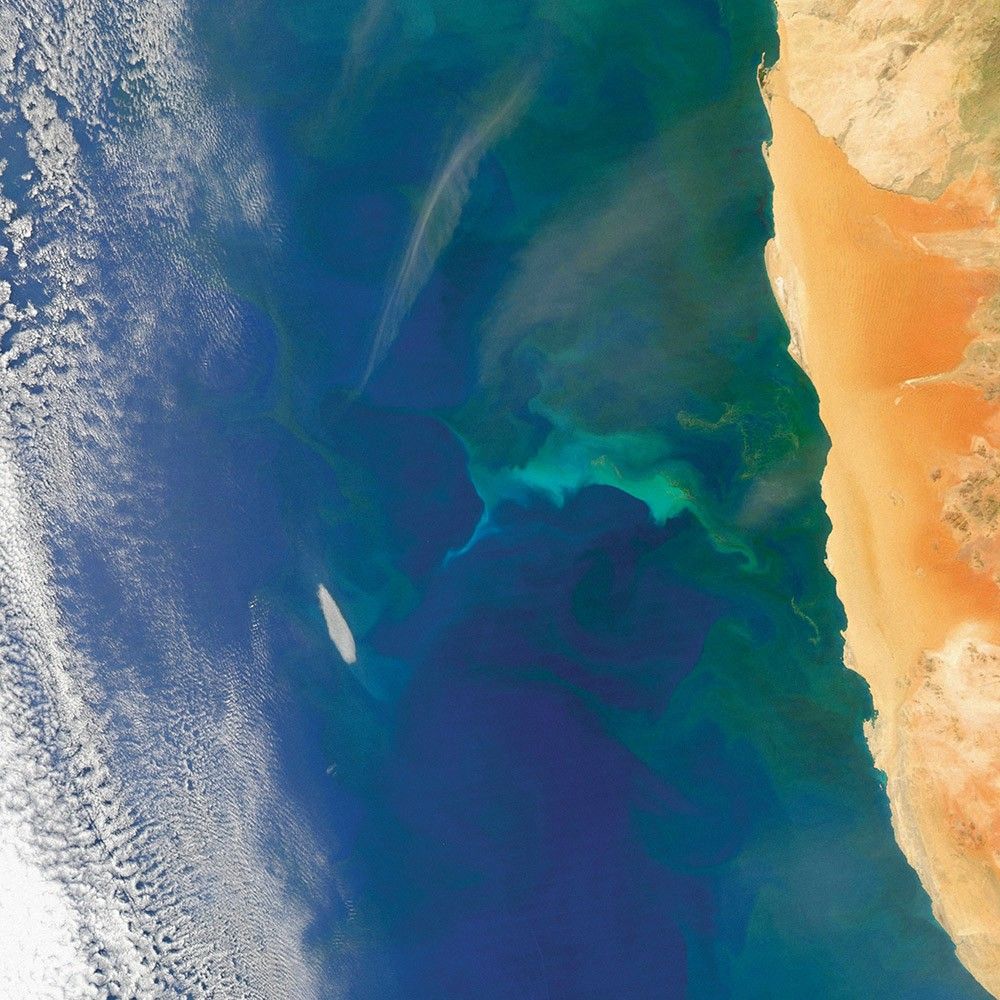

Namibia

Off the coast of Namibia, the Benguela Current flows north and west from South Africa. It is enriched by iron and other nutrients from the Southern Ocean and from dust blowing off African coastal deserts. Easterly winds push surface waters offshore and promote upwelling near the coast, which brings up cold, nutrient-rich waters from the deeper ocean. These interactions can make the ocean come alive with color.

Bacteria in oxygen-depleted bottom waters consume organic matter and produce large amounts of hydrogen sulfide. As that gas bubbles up into more oxygen-rich water, the sulfur precipitates out and floats near the surface in yellow-green patches.

Further offshore, milky green water may be a bloom of phytoplankton. As these organisms consume sunlight and nutrients, they also consume oxygen and sometimes deplete it from the water. At the same time, those oxygen-depleted waters help sulfur-producing bacteria thrive.

Åland Islands

-

Scandinavia

The Åland Islands lie in the Gulf of Bothnia, between Sweden and Finland. The archipelago consists of several large islands and roughly 6,500 small isles, many of them too small for human habitation. They are covered by pine and deciduous forest, meadows, and farmed fields. The region’s characteristic red rapakivi granite also stands out.

These rocks were formed during the Proterozoic Eon, hundreds of millions of years before the dinosaurs. Massive ice sheets later sculpted the landscape, but these days people cut and use the granite in buildings and pavement. Landsat 5 acquired this image in June 2011.

Crater Lakes with Clear Water

-

Canada

About 290 million years ago, two large asteroids smashed into Earth. The massive craters they left behind—now the Clearwater Lakes, or Lac á l’Eau Claire—are still visible from space.

When they struck, the binary asteroids crashed into a part of Earth’s crust that was fairly close to the Equator. Since then, millions of years of plate tectonics have pushed the craters northward into what is now northwestern Quebec. A mere 20,000 years ago, massive ice sheets advanced and retreated, scouring the land of soil and rock during cool periods and then carving deep channels and rinsing the landscape with meltwater during warmer periods. The erosion was so complete that many land surfaces were scraped down to underlying bedrock, exposing some of the oldest rocks in the world. Meanwhile, the meltwater from retreating glaciers left a dense network of linear lakes and streams that now dominate the surface.

Mergui Archipelago

-

Southeast Asia

Near the border of Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand, more than 800 islands rise amid extensive coral reefs in the Andaman Sea. This is the Mergui Archipelago.

Captain Thomas Forrest of the East India Company first reported on the region to Europeans after a 1782 expedition, describing islands inhabited by a nomadic fishing culture. These people, known as the Moken, still call the archipelago home and mostly live a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The small population of the archipelago has helped preserve its high diversity of plants and animals, making it a compelling travel spot for ecotourism—both above and below the water line.

In this view of Auckland Bay and Whale Bay, white swirling patterns in the near-shore waters are sediments that are carried out by rivers and deposited on the seafloor.

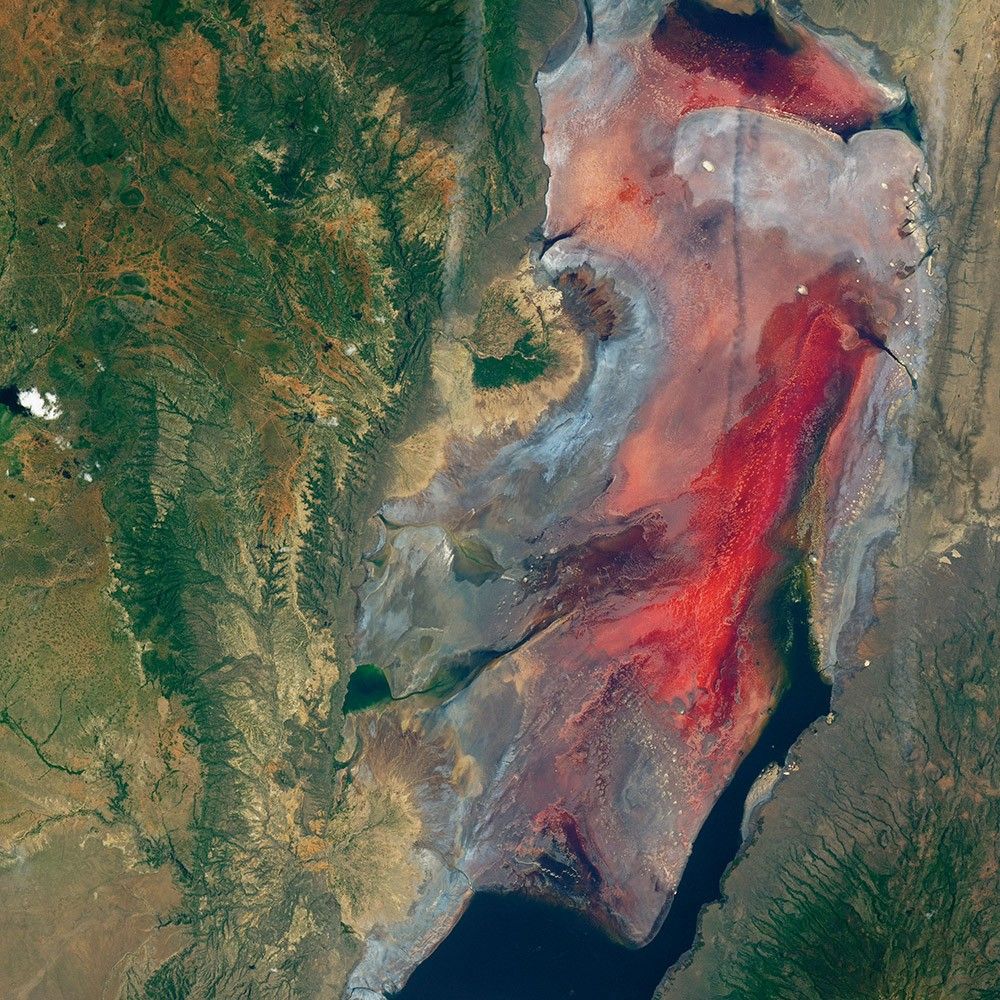

Scarlet Lake Natron

-

Tanzania

Lake Natron is mostly inhospitable to life, but it is gorgeous to the eye. The lake in Tanzania receives less than 500 millimeters (20 inches) of rain in most years. Evaporation usually exceeds that amount, and the lake needs input from some local rivers to maintain a water supply in the dry season.

This Landsat 8 image from March 2017 shows Lake Natron’s chromatic charisma. Volcanism helps make the unusual color. Nearby volcanoes produce molten mixtures of sodium carbonate and calcium carbonate salts that move through faults and well up in hot springs. This briny, alkaline environment is too harsh for most common types of life, but salt-loving microorganisms (haloarchaea) bloom in the shallow pools and impart pink and red colors to the water.

Swirling Bloom off Patagonia

-

Argentina

Interesting art often springs out of the convergence of different ideas and influences. And so it is with nature.

Off the coast of Argentina, two strong ocean currents converge and often stir up a colorful brew, as shown in this Aqua image from December 2010.

This milky green and blue bloom formed on the continental shelf off of Patagonia, where warmer, saltier waters from the subtropics meet colder, fresher waters flowing from the south. Where these currents collide, turbulent eddies and swirls form, pulling nutrients up from the deep ocean. The nearby Rio de la Plata also deposits nitrogen- and iron-laden sediment into the sea. Add in some midsummer sunlight, and you have a bountiful feast for microscopic, floating plants known as phytoplankton, which form the center of the ocean food web.