Fast facts: What is the Habitable Zone?

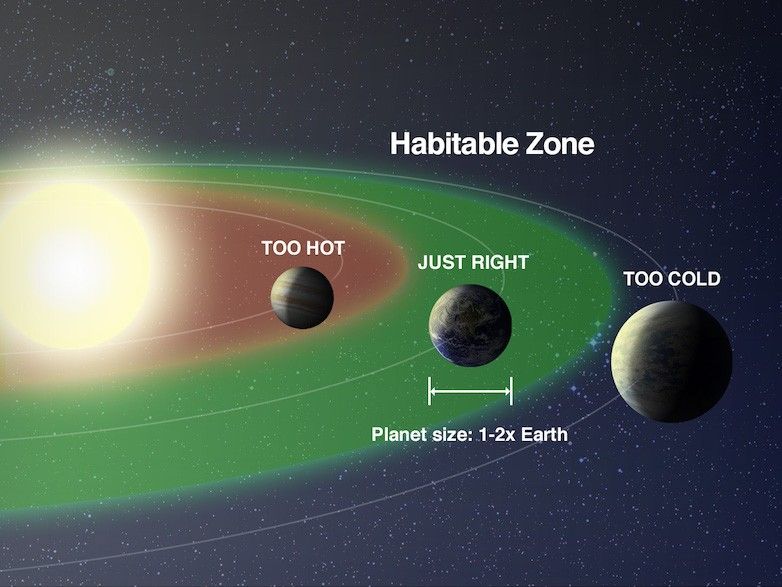

The definition of “habitable zone” is the distance from a star at which liquid water could exist on orbiting planets’ surfaces. Habitable zones are also known as “Goldilocks zones,” where conditions might be just right — not too hot, not too cold — for life.

NASA/JPL-Caltech

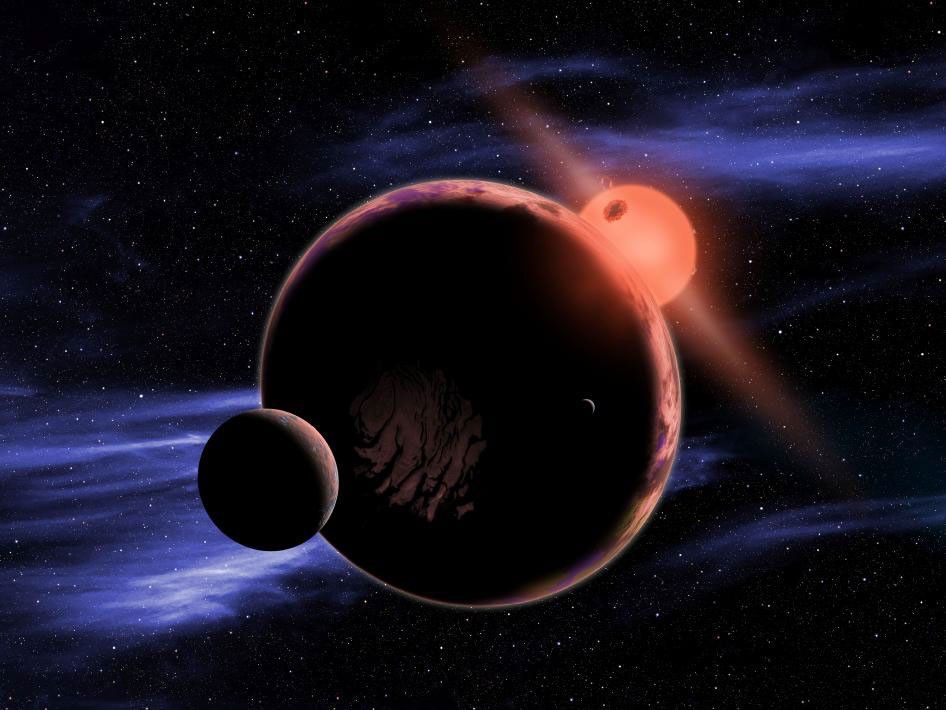

When searching for possibly habitable exoplanets, it helps to start with worlds similar to our own. But what does “similar” mean? Many rocky planets have been detected in Earth’s size-range: a point in favor of possible life. Based on what we’ve observed in our own solar system, large, gaseous worlds like Jupiter seem far less likely to offer habitable conditions. But most of these Earth-sized worlds have been detected orbiting red-dwarf stars; Earth-sized planets in wide orbits around Sun-like stars are much harder to detect.

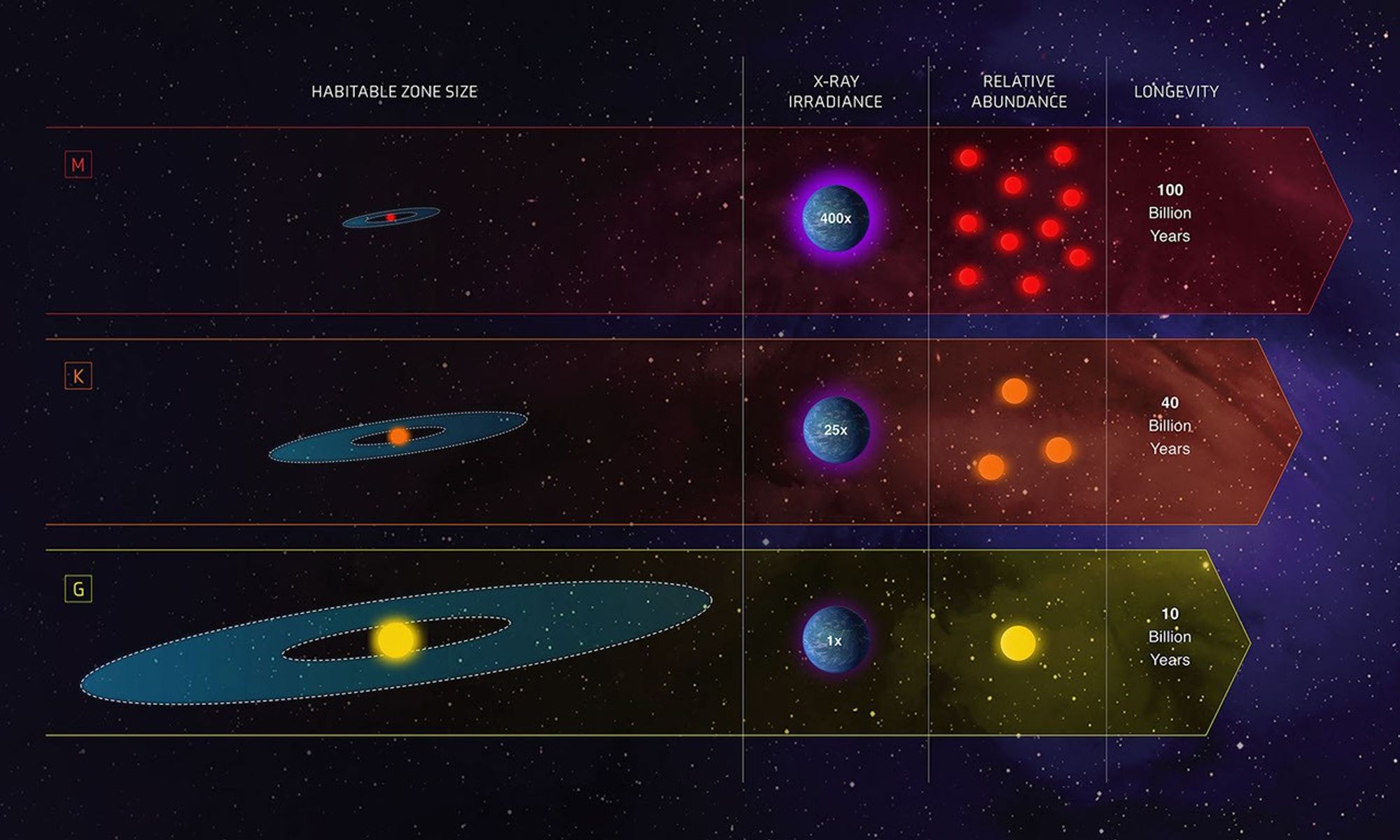

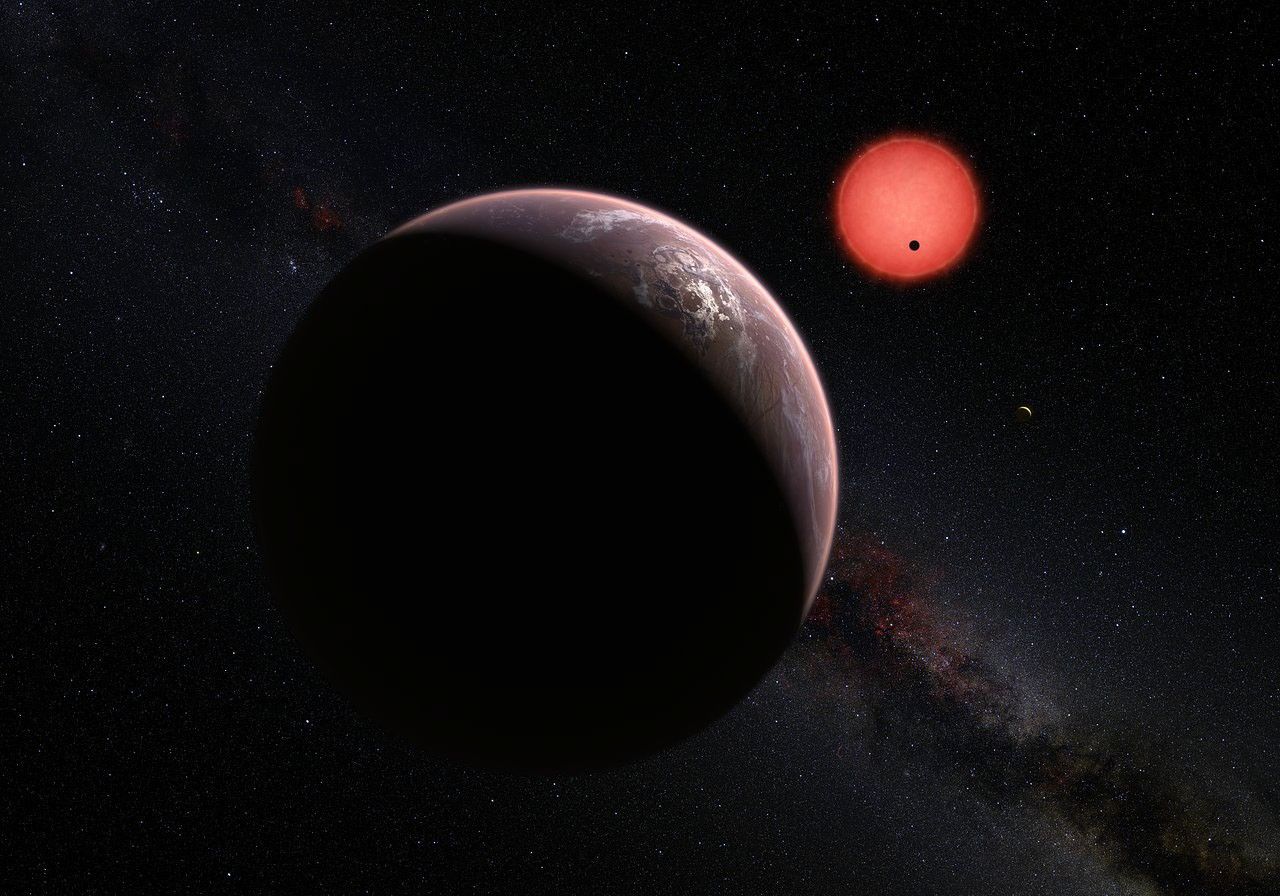

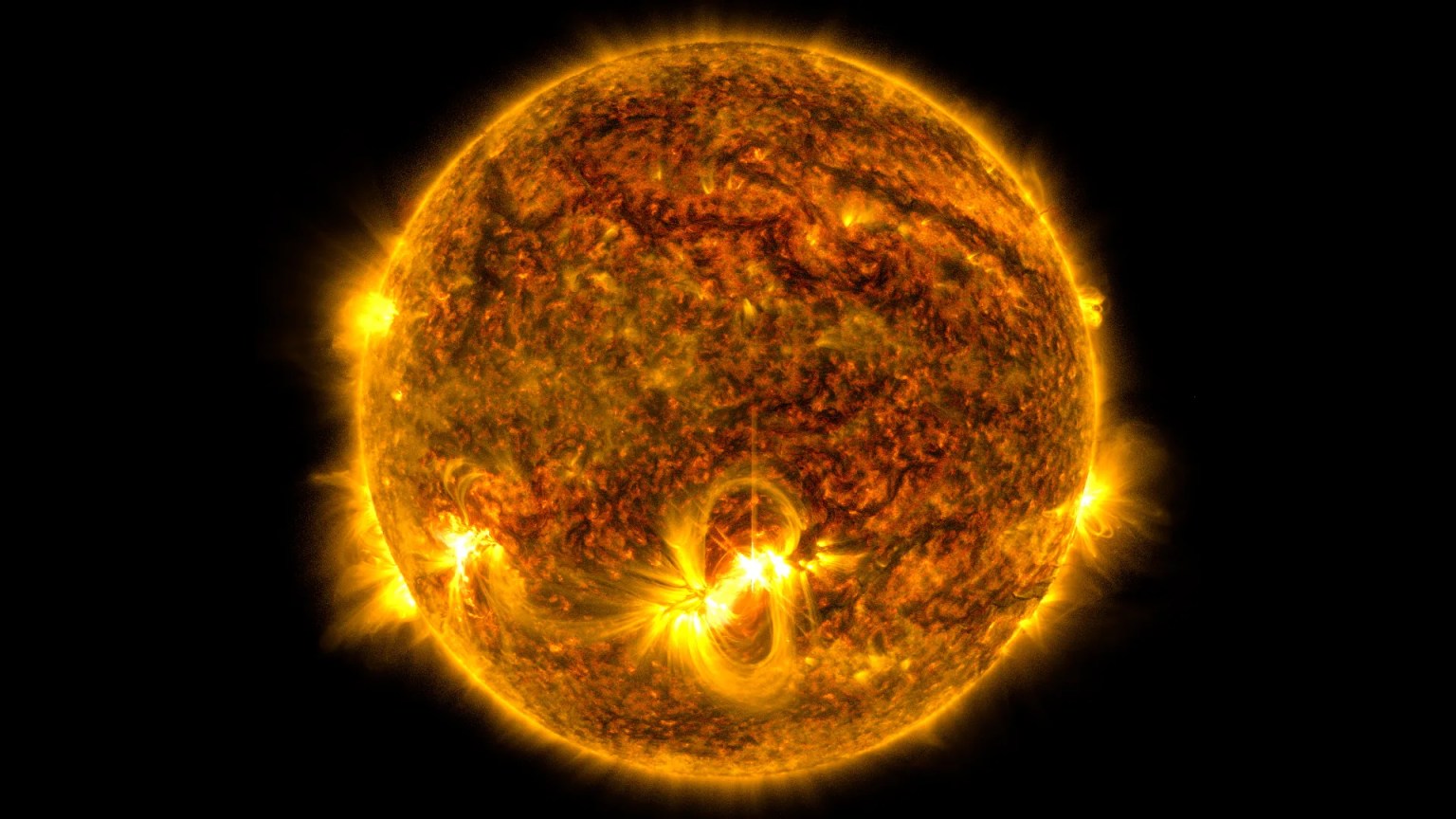

And, of course, when talking about habitable exoplanets, we’re really talking about their stars, the dominant force in any planetary system. Habitable zones potentially capable of hosting life-bearing planets are wider for hotter stars. Smaller, dimmer red dwarfs, the most common type in our Milky Way galaxy, have much tighter habitable zones as in the TRAPPIST-1 system. Planets in a red dwarf's comparatively narrow habitable zone, which is very close to the star, are exposed to extreme levels of X-ray and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which can be up to hundreds of thousands of times more intense than what Earth receives from the Sun.

Where Are We Looking for Life, and Why?

An old joke offers an answer: Asked why, on a dark night, he was looking for his missing car keys beneath a street lamp, the man answered, "because the light's better." Life on other planets might be like nothing on Earth – it could be life as we don't know it. But it makes sense, at least at first, to search for something more familiar. Life as we know it should be easier to find. And "the light's better" in the habitable zone, or the area around a star where planetary surface temperatures could allow the pooling of water.

Other similarities to Earth come into sharper focus in the search for life. Many rocky planets have been detected in Earth’s size-range: a point in favor of possible life. Based on what we’ve observed in our own solar system, large, gaseous worlds like Jupiter seem far less likely to offer habitable conditions. But most of these Earth-sized worlds have been detected orbiting red-dwarf stars; Earth-sized planets in wide orbits around Sun-like stars are much harder to detect. Yet these red-dwarfs have a potentially deadly habit, especially in their younger years: Powerful flares tend to erupt with some frequency from their surfaces. These could sterilize closely orbiting planets where life had only begun to get a toehold. That’s a strike against possible life.

Because our Sun has nurtured life on Earth for nearly 4 billion years, conventional wisdom would suggest that stars like it would be prime candidates in the search for other potentially habitable worlds. G-type yellow stars like our Sun, however, are shorter-lived and less common in our galaxy.

Stars slightly cooler and less luminous than our Sun — called orange dwarfs — are considered by some scientists as potentially better for advanced life. They can burn steadily for tens of billions of years. This opens up a vast timescape for biological evolution to pursue an infinity of experiments for yielding robust life forms. And, for every star like our Sun there are three times as many orange dwarfs in the Milky Way.

K dwarfs, are the true "Goldilocks stars," said Edward Guinan of Villanova University, Villanova, Pennsylvania. "K-dwarf stars are in the 'sweet spot,' with properties intermediate between the rarer, more luminous, but shorter-lived solar-type stars (G stars) and the more numerous red dwarf stars (M stars). The K stars, especially the warmer ones, have the best of all worlds. If you are looking for planets with habitability, the abundance of K stars pump up your chances of finding life."

Exoplanet temperature, size, star type: the galaxy offers up a menu of worlds that echo aspects of our own, yet at the same time are vastly different.

No Atmosphere Seen on TRAPPIST-1 D; Research Continues on Its Earth-Sized Siblings

With seven-Earth sized worlds in the habitable zone, the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanet system has compelled attention since its 2017 discovery. Now, preliminary data from the James Webb Space Telescope shows the “third rock” in this distant solar system, TRAPPIST-1 d, apparently has no atmosphere, but scientists are continuing their studies, and the search for potential atmospheres and water on the system’s outer planets.

Read the article: ‘Webb Narrows Atmospheric Possibilities for Earth-sized Exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 d’

The Hunt for Habitable Worlds

The Target Star Catalog is a guide to intriguing nearby stars that astronomers want to study with future missions, such as the Habitable Worlds Observatory, which will be built specifically to find and observe Earth-like exoplanets, to search for signs of life.

Browse the Target Star Catalog