Voyager 2

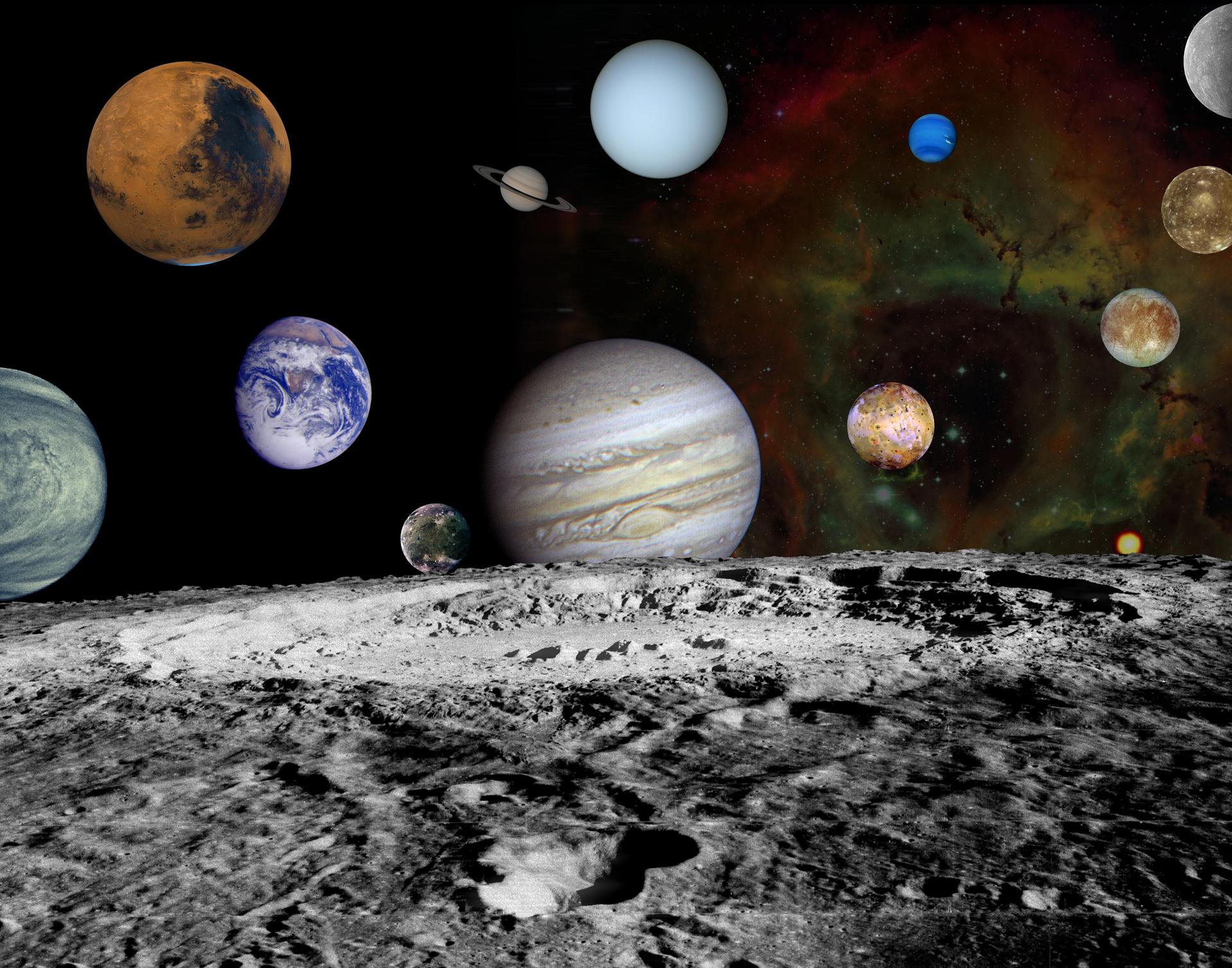

First to visit all four giant planets

What is Voyager 2?

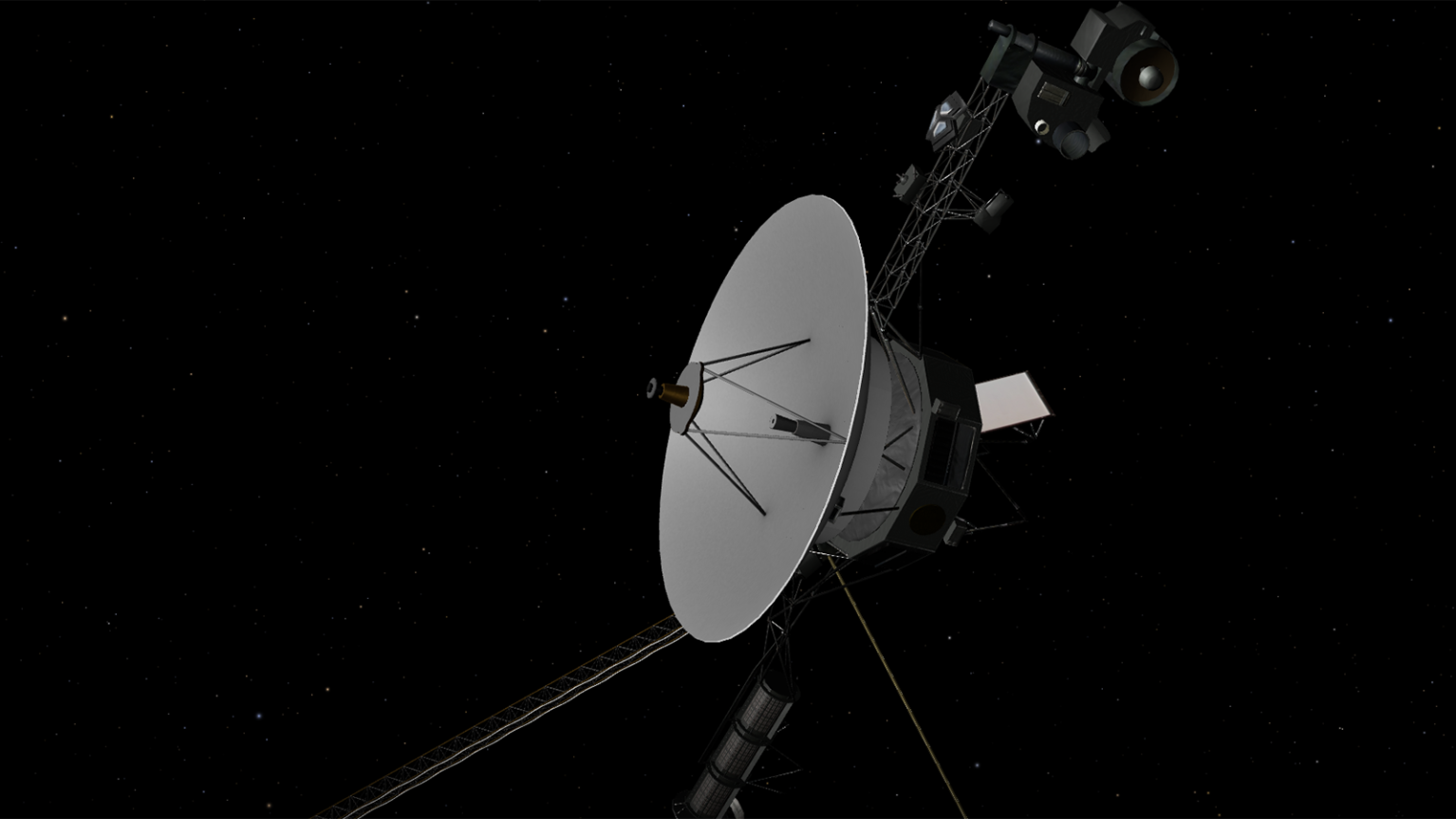

NASA's Voyager 2 is the second spacecraft to enter interstellar space. On Dec. 10, 2018, the spacecraft joined its twin – Voyager 1 – as the only human-made objects to enter the space between the stars.

- Voyager 2 is the only spacecraft to study all four of the solar system's giant planets at close range.

- Voyager 2 discovered a 14th moon at Jupiter.

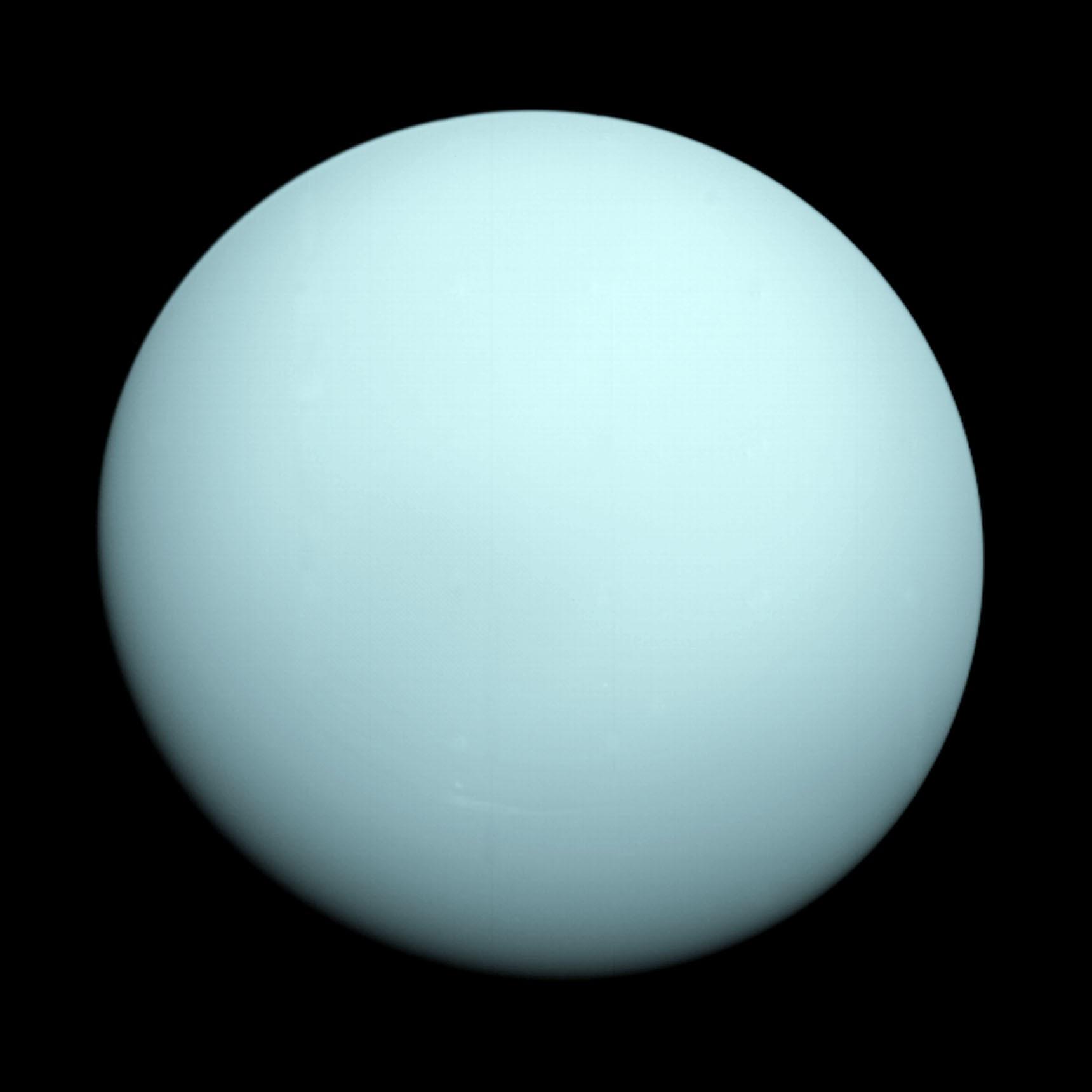

- Voyager 2 was the first human-made object to fly past Uranus.

- At Uranus, Voyager 2 discovered 10 new moons and two new rings.

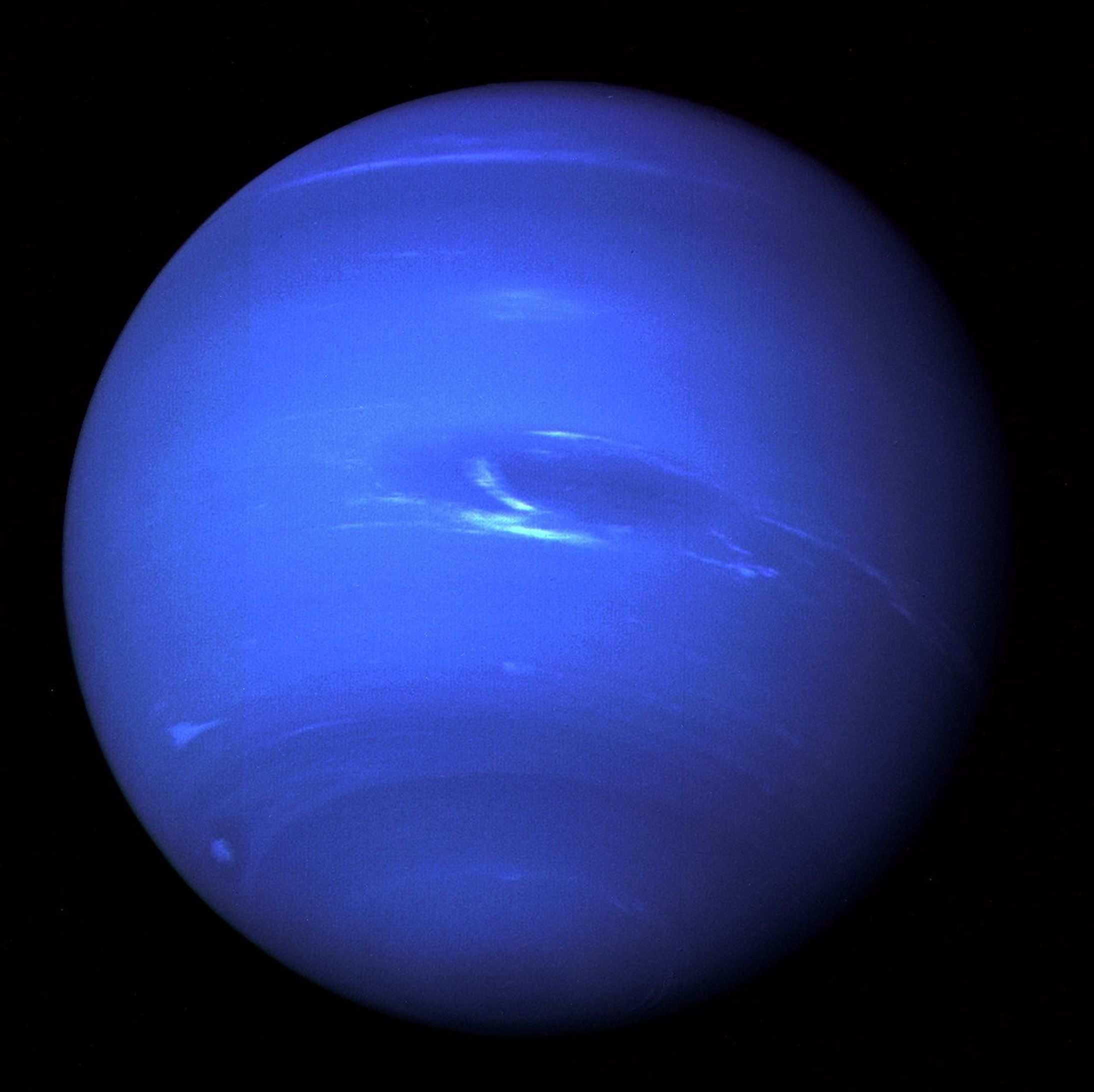

- Voyager 2 was the first human-made object to fly by Neptune.

- At Neptune, Voyager 2 discovered five moons, four rings, and a "Great Dark Spot."

In Depth: Voyager 2

| Nation | United States of America (USA) |

| Objective(s) | Jupiter Flyby, Saturn Flyby, Uranus Flyby, Neptune Flyby |

| Spacecraft | Voyager 2 |

| Spacecraft Mass | 1,592 pounds (721.9 kilograms) |

| Mission Design and Management | NASA / JPL |

| Launch Vehicle | Titan IIIE-Centaur (TC-7 / Titan no. 23E-7 / Centaur D-1T) |

| Launch Date and Time | Aug. 20, 1977 / 14:29:44 UT |

| Key Dates | July 9, 1979: Jupiter Flyby Aug 25, 1981: Saturn Flyby Jan 24, 1986: Uranus Flyby Aug 25, 1989: Neptune Flyby Aug 30, 2007: Crossed Termination Shock Nov 25, 2018: Entered Interstellar Space |

| Launch Site | Cape Canaveral, Fla. / Launch Complex 41 |

| Scientific Instruments | 1. Imaging Science System (ISS) 2. Ultraviolet Spectrometer (UVS) 3. Infrared Interferometer Spectrometer (IRIS) 4. Planetary Radio Astronomy Experiment (PRA) 5. Photopolarimeter (PPS) 6. Triaxial Fluxgate Magnetometer (MAG) 7. Plasma Spectrometer (PLS) 8. Low-Energy Charged Particles Experiment (LECP) 9. Plasma Waves Experiment (PWS) 10. Cosmic Ray Telescope (CRS) 11. Radio Science System (RSS) |

Results

The two-spacecraft Voyager missions were designed to replace original plans for a “Grand Tour” of the planets that would have used four highly complex spacecraft to explore the five outer planets during the late 1970s.

NASA canceled the plan in January 1972 largely due to anticipated costs (projected at $1 billion) and instead proposed to launch only two spacecraft in 1977 to Jupiter and Saturn. The two spacecraft were designed to explore the two gas giants in more detail than the two Pioneers (Pioneers 10 and 11) that preceded them.

In 1974, mission planners proposed a mission in which, if the first Voyager was successful, the second one could be redirected to Uranus and then Neptune using gravity assist maneuvers.

Each of the two spacecraft was equipped with a slow-scan color TV camera to take images of the planets and their moons and each also carried an extensive suite of instruments to record magnetic, atmospheric, lunar, and other data about the planetary systems.

The design of the two spacecraft was based on the older Mariners, and they were known as Mariner 11 and Mariner 12 until March 7, 1977, when NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher (1919-1991) announced that they would be renamed Voyager.

Power was provided by three plutonium oxide radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) mounted at the end of a boom.

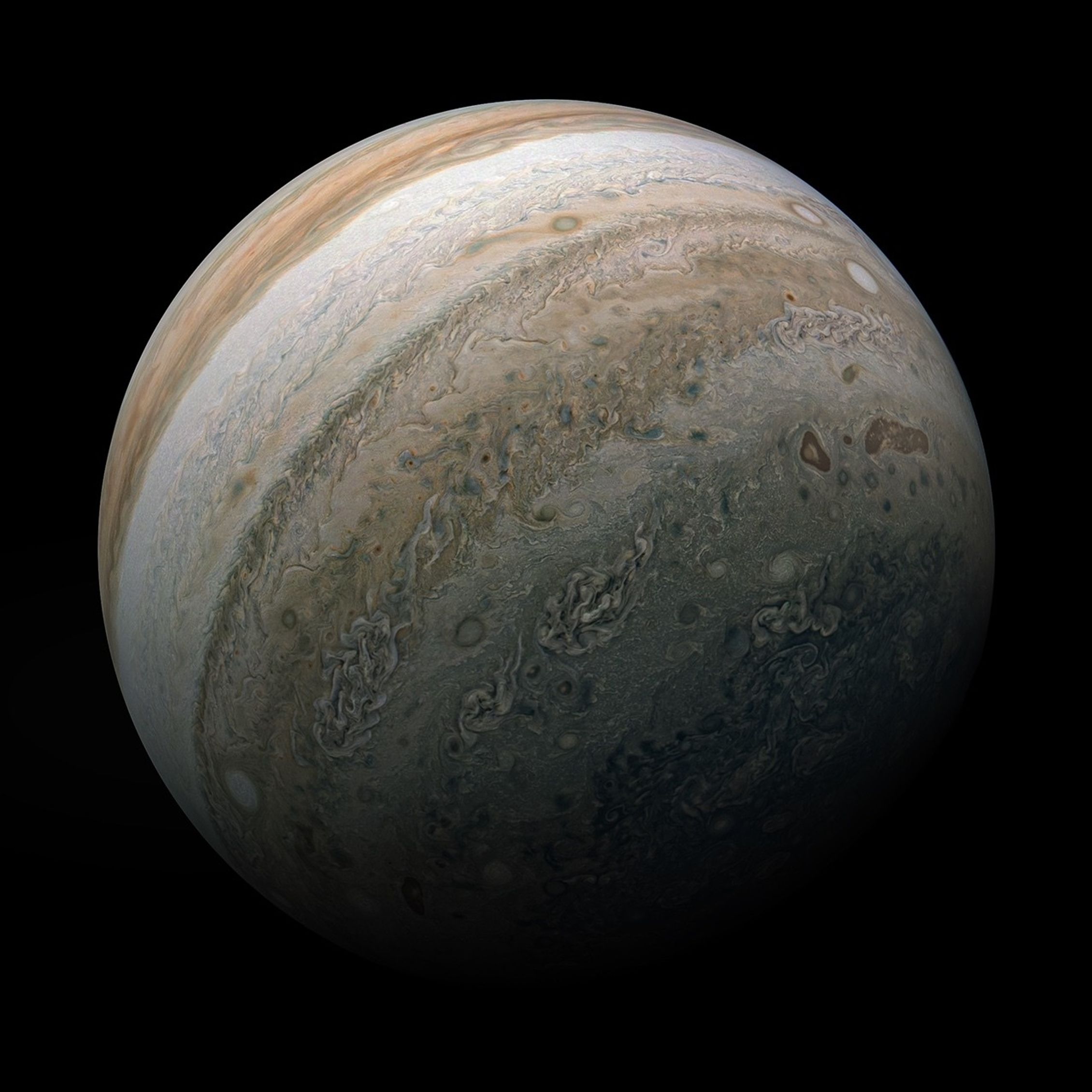

Voyager 2 at Jupiter

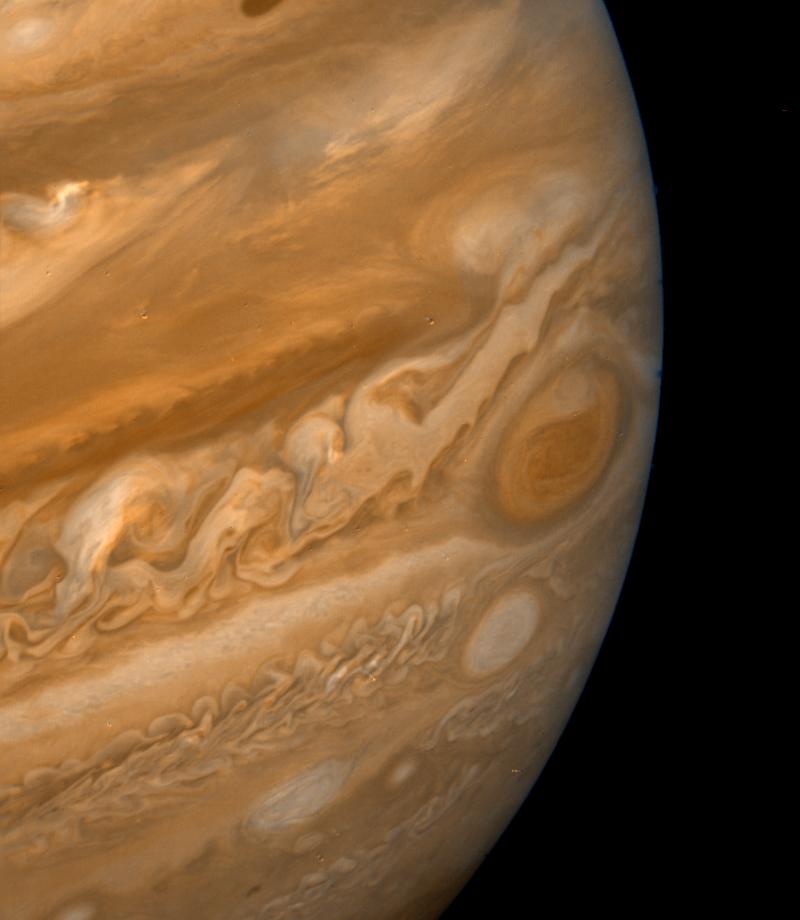

Voyager 2 began transmitting images of Jupiter April 24, 1979, for time-lapse movies of atmospheric circulation. Unlike Voyager 1, Voyager 2 made close passes to the Jovian moons on its way into the system, with scientists especially interested in more information from Europa and Io (which necessitated a 10 hour-long “volcano watch”).

During its encounter, it relayed back spectacular photos of the entire Jovian system, including its moons Callisto, Ganymede, Europa (at a range of about 127,830 miles or 205,720 kilometers, much closer than Voyager 1), Io, and Amalthea, all of which had already been surveyed by Voyager 1.

Voyager 2’s closest encounter to Jupiter was at 22:29 UT July 9, 1979, at a range of about 400,785 miles (645,000 kilometers). It transmitted new data on the planet’s clouds, its newly discovered four moons, and ring system, as well as 17,000 new pictures.

When the earlier Pioneers flew by Jupiter, they detected few atmospheric changes from one encounter to the second, but Voyager 2 detected many significant changes, including a drift in the Great Red Spot as well as changes in its shape and color.

With the combined cameras of the two Voyagers, at least 80% of the surfaces of Ganymede and Callisto were mapped out to a resolution of about 3 miles (5 kilometers).

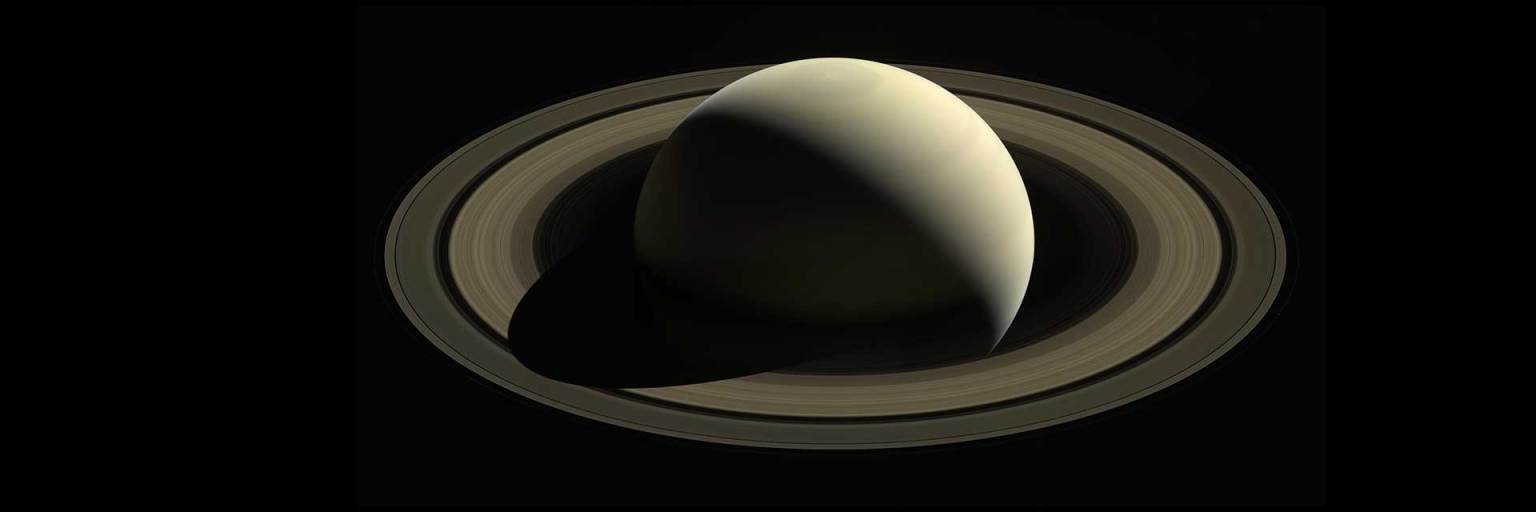

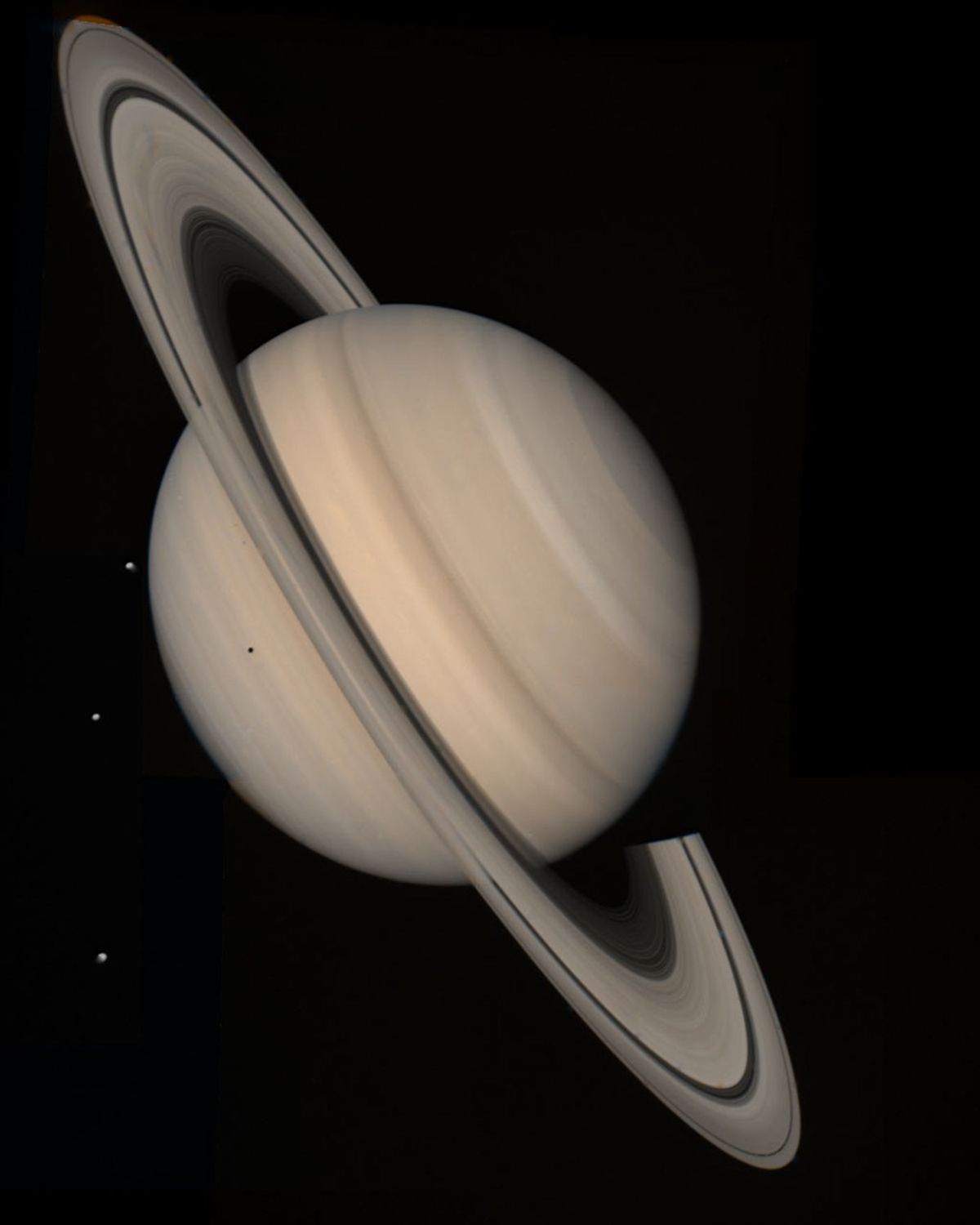

Voyager 2 at Saturn

Following a course correction two hours after its closest approach to Jupiter, Voyager 2 sped to Saturn – its trajectory determined to a large degree by a decision made in January 1981, to try to send the spacecraft to Uranus and Neptune later in the decade.

Its encounter with the sixth planet began Aug. 22, 1981, two years after leaving the Jovian system, with imaging of the moon Iapetus. Once again, Voyager 2 repeated the photographic mission of its predecessor, although it actually flew about 14,290 miles (23,000 kilometers) closer to Saturn. The closest encounter to Saturn was at 01:21 UT Aug. 26, 1981, at a range of about 63,000 miles (101,000 kilometers).

The spacecraft provided more detailed images of the ring “spokes” and kinks, and also the F-ring and its shepherding moons, all found by Voyager 1. Voyager 2’s data suggested that Saturn’s A-ring was perhaps only about 980 feet (300 meters) thick.

As it flew behind and up past Saturn, the probe passed through the plane of Saturn’s rings at a speed of 8 miles per second (13 kilometers per second). For several minutes during this phase, the spacecraft was hit by thousands of micron-sized dust grains that created “puff” plasma as they were vaporized. Because the vehicle’s attitude was repeatedly shifted by the particles, attitude control jets automatically fired many times to stabilize the vehicle.

During the encounter, Voyager 2 also photographed the Saturn moons Hyperion (the “hamburger moon”), Enceladus, Tethys, and Phoebe, as well as the more recently discovered Helene, Telesto and Calypso.

Voyager 2 at Uranus

Although Voyager 2 had fulfilled its primary mission goals with the two planetary encounters, mission planners directed the veteran spacecraft to Uranus—a journey that would take about 4.5 years.

In fact, its encounter with Jupiter was optimized in part to ensure that future planetary flybys would be possible.

The Uranus encounter’s geometry was also defined by the possibility of a future encounter with Neptune: Voyager 2 had only 5.5 hours of close study during its flyby.

The first human-made object to fly past Uranus, Voyager 2's long-range observations of the planet began Nov. 4, 1985, when signals took approximately 2.5 hours to reach Earth. Light conditions were 400 times less than terrestrial conditions. Closest approach to Uranus took place at 17:59 UT Jan. 24, 1986, at a range of about 50,640 miles (81,500 kilometers).

During its flyby, Voyager 2 discovered 10 new moons (given such names as Puck, Portia, Juliet, Cressida, Rosalind, Belinda, Desdemona, Cordelia, Ophelia, and Bianca – obvious allusions to Shakespeare, continuing a naming tradition begun in 1787), two new rings in addition to the “older” nine rings, and a magnetic field tilted at 55 degrees off-axis and off-center.

The spacecraft found wind speeds in Uranus’ atmosphere as high as 450 miles per hour (724 kilometers per hour) and found evidence of a boiling ocean of water some 497 miles (800 kilometers) below the top cloud surface. Its rings were found to be extremely variable in thickness and opacity.

Voyager 2 also returned spectacular photos of Miranda, Oberon, Ariel, Umbriel, and Titania, five of Uranus’ larger moons. In flying by Miranda at a range of only 17,560 miles (28,260 kilometers), the spacecraft came closest to any object so far in its nearly decade-long travels. Images of the moon showed a strange object whose surface was a mishmash of peculiar features that seemed to have no rhyme or reason. Uranus itself appeared generally featureless.

The spectacular news of the Uranus encounter was interrupted the same week by the tragic Challenger accident that killed seven astronauts during their space shuttle launch Jan. 28, 1986.

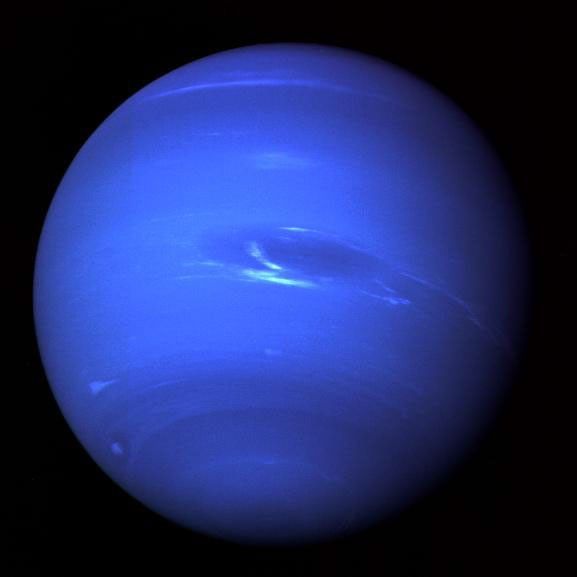

Voyager 2 at Neptune

Following the Uranus encounter, the spacecraft performed a single midcourse correction Feb. 14, 1986 – the largest ever made by Voyager 2 – to set it on a precise course to Neptune.

Voyager 2’s encounter with Neptune capped a 4.3 billion-mile (7 billion-kilometer) journey when, on Aug. 25, 1989, at 03:56 UT, it flew about 2,980 miles (4,800 kilometers) over the cloud tops of the giant planet, the closest of its four flybys. It was the first human-made object to fly by the planet. Its 10 instruments were still in working order at the time.

During the encounter, the spacecraft discovered six new moons (Proteus, Larissa, Despina, Galatea, Thalassa, and Naiad) and four new rings.

The planet itself was found to be more active than previously believed, with 680-mile (1,100-kilometer) per hour winds. Hydrogen was found to be the most common atmospheric element, although the abundant methane gave the planet its blue appearance.

Images revealed details of the three major features in the planetary clouds – the Lesser Dark Spot, the Great Dark Spot, and Scooter.

Voyager photographed two-thirds of Neptune’s largest moon Triton, revealing the coldest known planetary body in the solar system and a nitrogen ice “volcano” on its surface. Spectacular images of its southern hemisphere showed a strange, pitted, cantaloupe-type terrain.

The flyby of Neptune concluded Voyager 2’s planetary encounters, which spanned an amazing 12 years in deep space, virtually accomplishing the originally planned “Grand Tour” of the solar system – at least in terms of targets reached, if not in science accomplished.

Voyager 2's Interstellar Mission

Once past the Neptune system, Voyager 2 followed a course below the ecliptic plane and out of the solar system. Approximately 35 million miles (56 million kilometers) past the encounter, Voyager 2’s instruments were put in low-power mode to conserve energy.

After the Neptune encounter, NASA formally renamed the entire project the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM).

Of the four spacecraft sent out to beyond the environs of the solar system in the 1970s, three of them – Voyagers 1 and 2 and Pioneer 11 – were all heading in the direction of the solar apex, i.e., the apparent direction of the Sun’s travel in the Milky Way galaxy, and thus would be expected to reach the heliopause earlier than Pioneer 10, which was headed in the direction of the heliospheric tail.

In November 1998, 21 years after launch, nonessential instruments were permanently turned off, leaving seven instruments still operating.

At 9.6 miles per second (15.4 kilometers per second) relative to the Sun, it will take about 19,390 years for Voyager 2 to traverse a single light year.

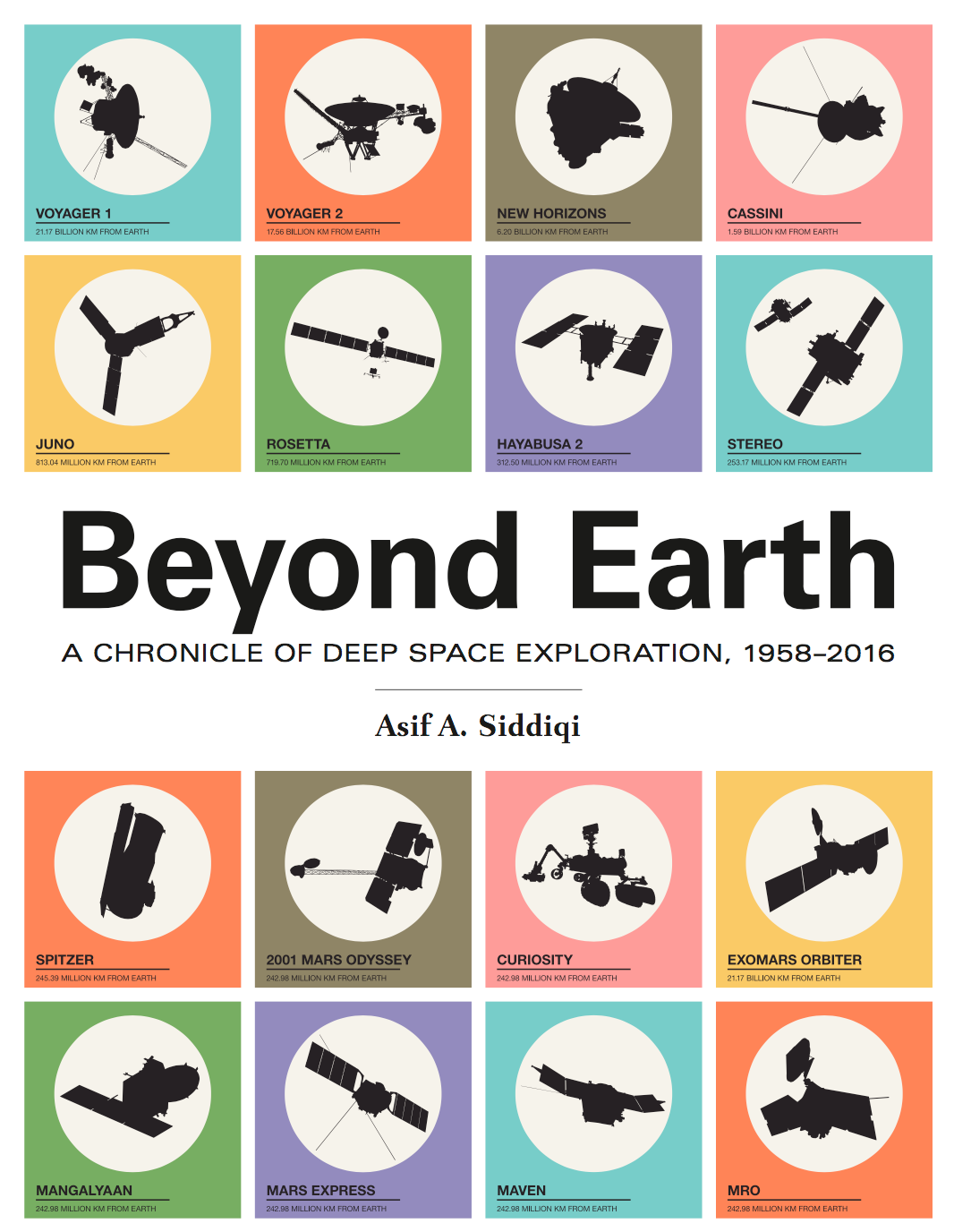

Asif Siddiqi

Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration

Through the turn of the century, NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) continued to receive ultraviolet and particle fields data. For example, on Jan. 12, 2001, an immense shock wave that had blasted out of the outer heliosphere on July 14, 2000, finally reached Voyager 2. During its six-month journey, the shock wave had plowed through the solar wind, sweeping up and accelerating charged particles. The spacecraft provided important information on high-energy shock-energized ions.

On Aug. 30, 2007, Voyager 2 passed the termination shock and then entered the heliosheath. By Nov. 5, 2017, the spacecraft was 116.167 AU (about 10.8 billion miles or about 17.378 billion kilometers) from Earth, moving at a velocity of 9.6 miles per second (15.4 kilometers per second) relative to the Sun, heading in the direction of the constellation Telescopium. At this velocity, it would take about 19,390 years to traverse a single light-year.

On July 8, 2019, Voyager 2 successfully fired up its trajectory correction maneuver thrusters and will be using them to control the pointing of the spacecraft for the foreseeable future. Voyager 2 last used those thrusters during its encounter with Neptune in 1989.

The spacecraft's aging attitude control thrusters have been experiencing degradation that required them to fire an increasing and untenable number of pulses to keep the spacecraft's antenna pointed at Earth. Voyager 1 had switched to its trajectory correction maneuver thrusters for the same reason in January 2018.

To ensure that both vintage robots continue to return the best scientific data possible from the frontiers of space, mission engineers are implementing a new plan to manage them. The plan involves making difficult choices, particularly about instruments and thrusters.

.png?w=1920&h=1080&fit=clip&crop=faces%2Cfocalpoint)