The Voyager mission was officially approved in May 1972. Through the dedicated efforts of many skilled personnel for over three decades, the Voyagers have returned knowledge about the outer planets that had not existed in all of the preceding history of astronomy and planetary science. The Voyager spacecrafts are still performing like champs.

It must come as no surprise that there are many remarkable, "gee-whiz" facts associated with the various aspects of the Voyager mission. These tidbits have been summarized below in appropriate categories. Several may seem difficult to believe, but they are all true and accurate.

Overall Mission

The total cost of the Voyager mission from May 1972 through the Neptune encounter (including launch vehicles, radioactive power source (RTGs), and DSN tracking support) is 865 million dollars. At first, this may sound very expensive, but the fantastic returns are a bargain when we place the costs in the proper perspective. It is important to realize that:

- on a per-capita basis, this is only 8 cents per U.S. resident per year, or roughly half the cost of one candy bar each year since project inception. the entire cost of Voyager is a fraction of the daily interest on the U.S. national debt.

- A total of 11,000 workyears were devoted to the Voyager project through the Neptune encounter. This is equivalent to one-third the amount of effort estimated to complete the great pyramid at Giza to King Cheops.

A total of five trillion bits of scientific data had been returned to Earth by both Voyager spacecraft at the completion of the Neptune encounter. This represents enough bits to fill more than seven thousand music CDs.

The sensitivity of our deep-space tracking antennas located around the world is truly amazing. The antennas must capture Voyager information from a signal so weak that the power striking the antenna is only 10 exponent -16 watts (1 part in 10 quadrillion). A modern-day electronic digital watch operates at a power level 20 billion times greater than this feeble level.

Voyager Spacecraft

Each Voyager spacecraft comprises 65,000 individual parts. Many of these parts have a large number of "equivalent" smaller parts such as transistors. One computer memory alone contains over one million equivalent electronic parts, with each spacecraft containing some five million equivalent parts. Since a color TV set contains about 2500 equivalent parts, each Voyager has the equivalent electronic circuit complexity of some 2000 color TV sets.

Like the HAL computer aboard the ship Discovery from the famous science fiction story 2001: A Space Odyssey, each Voyager is equipped with computer programming for autonomous fault protection. The Voyager system is one of the most sophisticated ever designed for a deep-space probe. There are seven top-level fault protection routines, each capable of covering a multitude of possible failures. The spacecraft can place itself in a safe state in a matter of only seconds or minutes, an ability that is critical for its survival when round-trip communication times for Earth stretch to several hours as the spacecraft journeys to the remote outer solar system.

Both Voyagers were specifically designed and protected to withstand the large radiation dosage during the Jupiter swing-by. This was accomplished by selecting radiation-hardened parts and by shielding very sensitive parts. An unprotected human passenger riding aboard Voyager 1 during its Jupiter encounter would have received a radiation dose equal to one thousand times the lethal level.

The Voyager spacecraft can point its scientific instruments on the scan platform to an accuracy of better than one-tenth of a degree. This is comparable to bowling strike-after-strike ad infinitum, assuming that you must hit within one inch of the strike pocket every time. Such precision is necessary to properly center the narrow-angle picture whose square field-of-view would be equivalent to the width of a bowling pin.

To avoid smearing in Voyager's television pictures, spacecraft angular rates must be extremely small to hold the cameras as steady as possible during the exposure time. Each spacecraft is so steady that angular rates are typically 15 times slower than the motion of a clock's hour hand. But even this was not steady enough at Neptune, where light levels are 900 times fainter than those on Earth. Spacecraft engineers devised ways to make Voyager 30 times steadier than the hour hand on a clock.

The electronics and heaters aboard each nearly one-ton Voyager spacecraft can operate on only 400 watts of power, or roughly one-fourth that used by an average residential home in the western United States.

A set of small thrusters provides Voyager with the capability for attitude control and trajectory correction. Each of these tiny assemblies has a thrust of only three ounces. In the absence of friction, on a level road, it would take nearly six hours to accelerate a large car up to a speed of 48 km/h (30 mph) using one of the thrusters.

The Voyager scan platform can be moved about two axes of rotation. A thumb-sized motor in the gear train drive assembly (which turns 9000 revolutions for each single revolution of the scan platform) will have rotated five million revolutions from launch through the Neptune encounter. This is equivalent to the number of automobile crankshaft revolutions during a trip of 2725 km (1700 mi), about the distance from Boston,MA to Dallas,TX.

The Voyager gyroscopes can detect spacecraft angular motion as little as one ten-thousandth of a degree. The Sun's apparent motion in our sky moves over 40 times that amount in just one second.

The tape recorder aboard each Voyager has been designed to record and playback a great deal of scientific data. The tape head should not begin to wear out until the tape has been moved back and forth through a distance comparable to that across the United States. Imagine playing a two-hour video cassette on your home VCR once a day for the next 33 years, without a failure.

The Voyager magnetometers are mounted on a frail, spindly, fiberglass boom that was unfurled from a two-foot-long can shortly after the spacecraft left Earth. After the boom telescoped and rotated out of the cannister to an extension of nearly 13 meters (43 feet), the orientations of the magnetometer sensors were controlled to an accuracy better than two degrees.

Navigation

Each Voyager used the enormous gravity field of Jupiter to be hurled on to Saturn, experiencing a Sun-relative speed increase of roughly 35,700 mph. As total energy within the solar system must be conserved, Jupiter was initially slowed in its solar orbit---but by only one foot per trillion years. Additional gravity-assist swing-bys of Saturn and Uranus were necessary for Voyager 2 to complete its Grand Tour flight to Neptune, reducing the trip time by nearly twenty years when compared to the unassisted Earth-to-Neptune route.

The Voyager delivery accuracy at Neptune of 100 km (62 mi), divided by the trip distance or arc length traveled of 7,128,603,456 km (4,429,508,700 mi), is equivalent to the feat of sinking a 3630 km (2260 mi) golf putt, assuming that the golfer can make a few illegal fine adjustments while the ball is rolling across this incredibly long green.

Voyager's fuel efficiency (in terms of mpg) is quite impressive. Even though most of the launch vehicle's 700 ton weight is due to rocket fuel, Voyager 2's great travel distance of 7.1 billion km (4.4 billion mi) from launch to Neptune resultsed in a fuel economy of about 13,000 km per liter (30,000 mi per gallon). As Voyager 2 streaked by Neptune and coasts out of the solar system, this fuel economy just got better and better!

Science

The resolution of the Voyager narrow-angle television cameras is sharp enough to read a newspaper headline at a distance of 1 km (0.62 mi).

Pele, the largest of the volcanoes seen on Jupiter's moon Io, is throwing sulfur and sulfur-dioxide products to heights 30 times that of Mount Everest, and the fallout zone covers an area the size of France. The eruption of Mount St. Helens was but a tiny hiccup in comparison (admittedly, Io's surface-level gravity is some six times weaker than that of Earth).

The smooth water-ice surface of Jupiter's moon Europa may hide an ocean beneath, but some scientists believe any past oceans have turned to slush or ice. In 2010: Odyssey Two, Arthur C. Clarke wraps his story around the possibility of life developing within the oceans of Europa.

The rings of Saturn appeared to the Voyagers as a dazzling necklace of 10,000 strands. Trillions of ice particles and car-sized bergs race along each of the million-kilometer-long tracks, with the traffic flow orchestrated by the combined gravitational tugs of Saturn, a retinue of moons and moonlets, and even nearby ring particles. The rings of Saturn are so thin in proportion to their 171,000 km (106,000 mi) width that, if a full-scale model were to be built with the thickness of a phonograph record the model would have to measure four miles from its inner edge to its outer rim. An intricate tapestry of ring-particle patterns is created by many complex dynamic interactions that have spawned new theories of wave and particle motion.

Saturn's largest moon Titan was seen as a strange world with its dense atmosphere and variety of hydrocarbons that slowly fall upon seas of ethane and methane. To some scientists, Titan, with its principally nitrogen atmosphere, seemed like a small Earth whose evolution had long ago been halted by the arrival of its ice age, perhaps deep-freezing a few organic relics beneath its present surface.

The rings of Uranus are so dark that Voyager's challenge of taking their picture was comparable to the task of photographing a pile of charcoal briquettes at the foot of a Christmas tree, illuminated only by a 1 watt bulb at the top of the tree, using ASA-64 film. And Neptune light levels will be less than half those at Uranus.

The Future

Through the ages, astronomers have argued without agreeing on where the solar system ends. One opinion is that the boundary is where the Sun’s gravity no longer dominates – a point beyond the planets and beyond the Oort Cloud. This boundary is roughly about halfway to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri. Traveling at speeds of over 35,000 miles per hour, it will take the Voyagers nearly 40,000 years, and they will have traveled a distance of about two light years to reach this rather indistinct boundary.

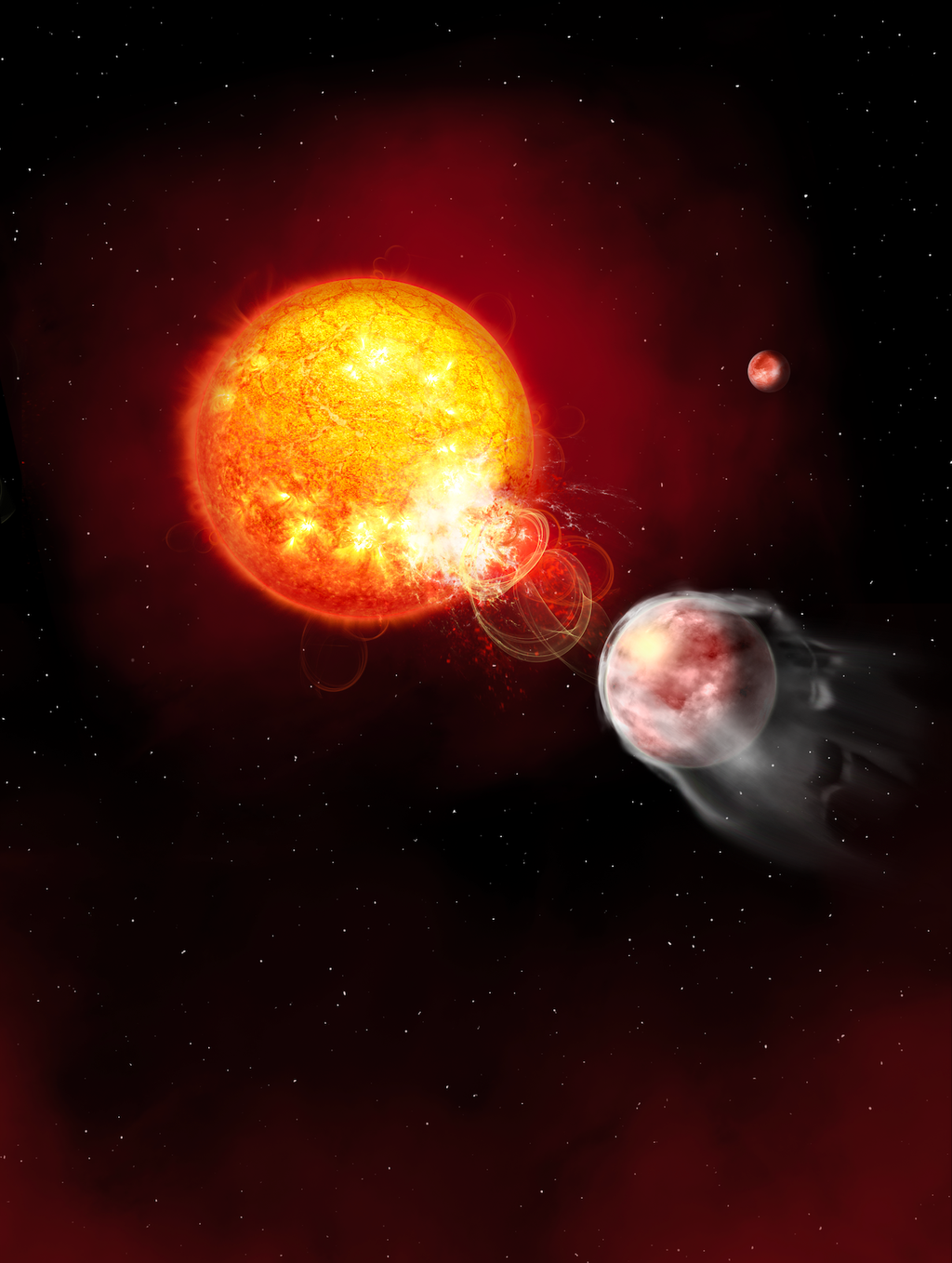

But there is a more definitive and unambiguous frontier, which the Voyagers will approach and pass through. This is the heliopause, which is the boundary area between the solar and the interstellar wind. When Voyager 1 crosses the solar wind termination shock, it will have entered into the heliosheath, the turbulent region leading up to the heliopause. When the Voyagers cross the heliopause, hopefully while the spacecraft are still able to send science data to Earth, they will be in interstellar space even though they will still be a very long way from the “edge of the solar system”. Once Voyager is in interstellar space, it will be immersed in matter that came from explosions of nearby stars. So, in a sense, one could consider the heliopause as the final frontier.

Barring any serious spacecraft subsystem failures, the Voyagers may survive until the early twenty-first century (~ 2025), when diminishing power and hydrazine levels will prevent further operation. Were it not for these dwindling consumables and the possibility of losing lock on the faint Sun, our tracking antennas could continue to "talk" with the Voyagers for another century or two!