How Do We Communicate With Webb?

Discover the global Deep Space Network and how it makes communication with Webb possible at any time.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope is located nearly 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth. How is information sent to and received from Webb over such a huge distance? Members of Webb’s mission team, along with many other mission groups, use the Deep Space Network (DSN), the largest and most sensitive scientific telecommunications system in the world.

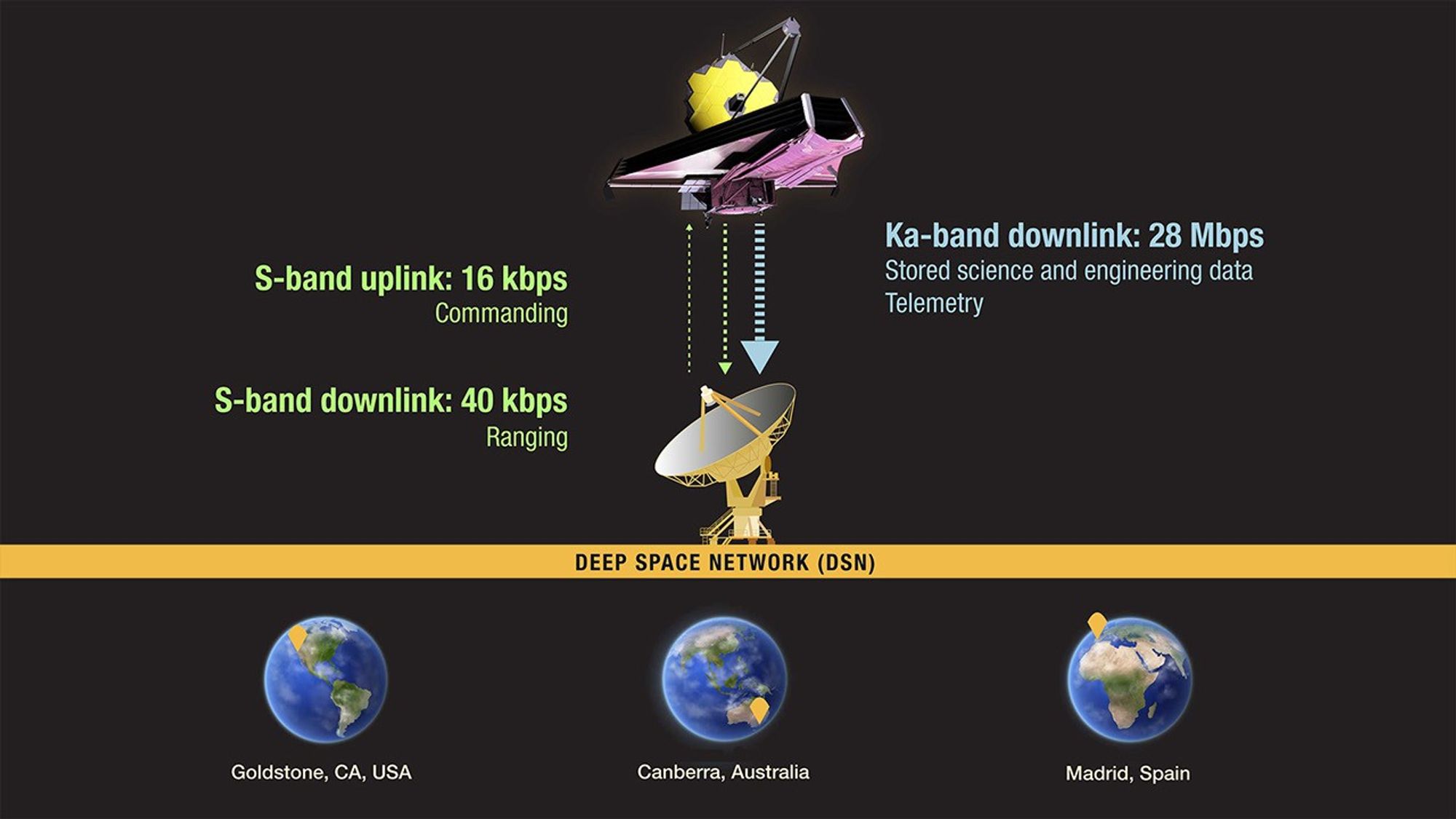

Operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), the DSN is an international array of giant radio antennas, each positioned 120 degrees apart at three sites: Goldstone, California; Canberra, Australia; and Madrid, Spain. This allows communication with Webb at any time of the day or night; as the Earth rotates and one of the antennas moves out of range, another moves into range.

Each of the DSN complexes has different sizes of antennas, including 70-meter (230-foot in diameter), 34-meter (111-foot in diameter), and 26-meter (85-foot in diameter) antennas. The DSN complexes use the 34-meter antennas to talk with Webb, with the 70-meter antennas as backups. The DSN supports different radio frequency allocations, such as the S-band and Ka-band frequencies that Webb uses. S-band has a lower bandwidth that is used to send commands to the spacecraft (e.g., start recorder playback), to receive engineering telemetry to monitor the health and safety of the observatory.

On average, the mission operations center at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, connects with Webb at least two to three times in a 24-hour period. There are a few things that have to happen before scheduling contact. Due to the fact that the DSN hosts almost 40 different missions, scheduling can get complicated.

The Flight Dynamics Facility at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center sends STScI the view periods during which the observatory is visible from one of the three different DSN sites. The mission scheduler compares those times to what is available in the DSN scheduling system, where other missions are competing for time with their spacecraft. There are instances when missions request the same resource at the same time. When this happens, the scheduler at JPL will negotiate with the missions to come to a compromise. Once all negotiations are complete, schedules are sent to the mission planners up to six months in advance. The first eight weeks of the schedule is fixed, with no changes allowed unless there is an emergency or important event with a spacecraft. The later periods are subject to continuing negotiations.

Once contact with Webb has been established according to the agreed-upon schedule, the Ka-band is used to downlink stored science and engineering data, and some telemetry from the spacecraft. The Ka-band is much more efficient for downloading than the S-band, accomplishing in a couple of hours what would take many days on the S-band. The high gain antenna on Webb is used for Ka-band downlink, and the medium gain antenna is used for S-band uplink and downlink when both antennas are pointed directly at one of the DSN sites for a contact. Most contact periods with Webb last from two to six hours.

During each contact, it is important to downlink as much data as possible since the telescope continually makes pre-programed science observations, acquiring more data that need to be stored. When not in contact with the mission operations center, Webb stores its data on a solid-state recorder. Once the data are downloaded they are ingested into the Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST) at STScI for processing and calibration, after which they are passed along to the scientists who planned the observation. MAST is the final, publicly accessible repository for all Webb data and many other missions, including the Hubble Space Telescope, Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), Gaia, and the retired Kepler and K2 missions, among many others.