An infrared telescope comes with an inherent design problem—it gives off heat. To capture infrared light from cosmic objects, the James Webb Space Telescope will have to be kept as cold as possible.

Webb’s Sunshield

Webb’s sunshield is one of the telescope’s most prominent features. It protects the telescope from the heat and light of the Sun, Moon, and Earth. The sunshield, about the size of a 20-car parking lot, consists of five layers—each about the thickness of plastic wrap. The layers do not touch, because that would allow the transfer of heat from one layer to the next. Coatings of aluminum also help cut down on warmth transmission.

The layers are made of a material called Kapton, also used in spacesuits and circuitry, which has the convenient properties of being heat resistant and strong. The sunshield is coated on the sunward side with silicon, which reflects and radiates away incoming sunlight.

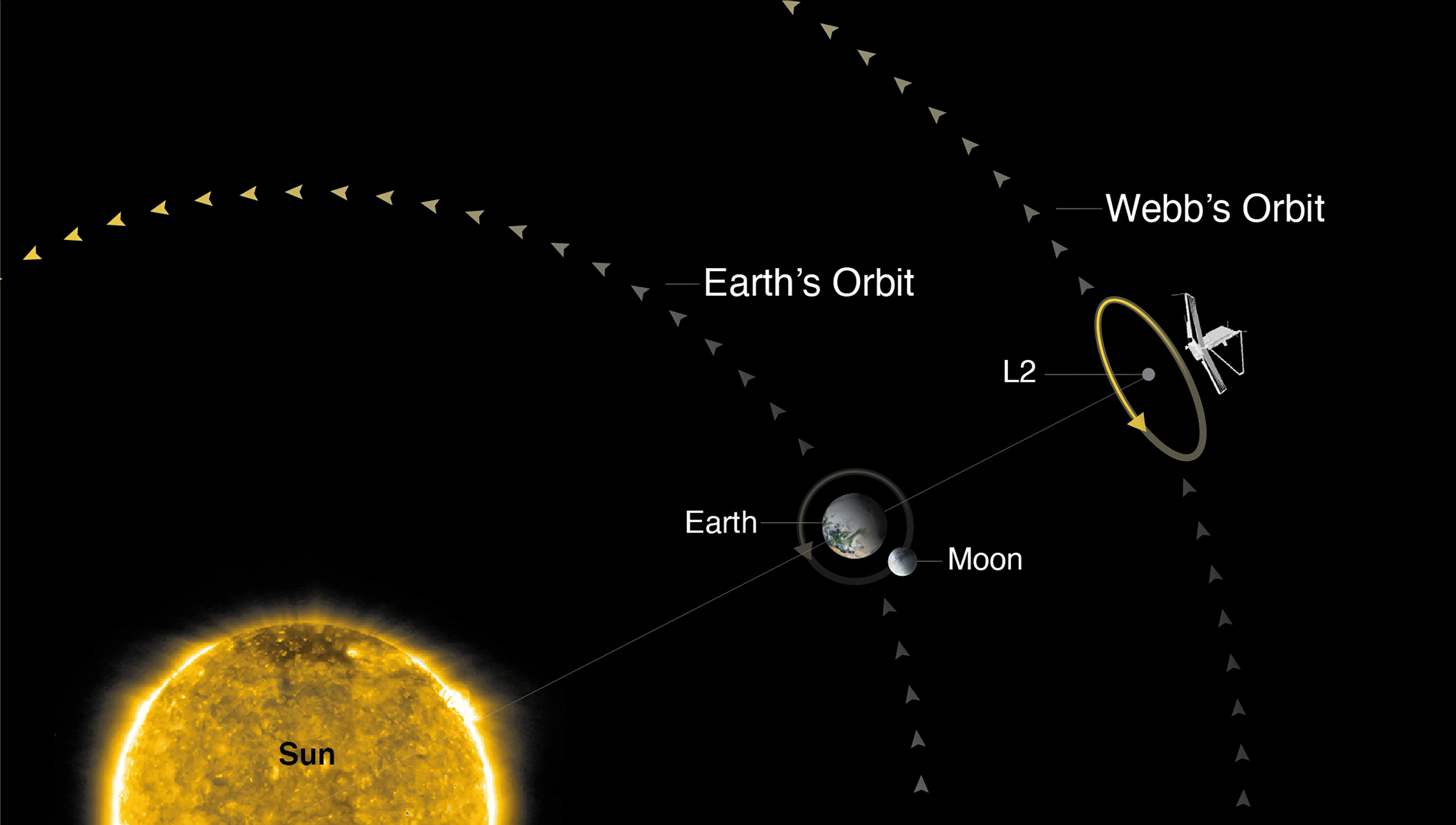

Webb’s Orbit

Webb’s distant orbit performs two functions. It places the telescope in a frigid environment, and makes it possible to position the telescope so it always has the Sun, Earth, and Moon on the same side, behind its sunshield. Webb was directed via an Ariane 5 launch vehicle toward the Second Sun-Earth Lagrange Point (L2), 1.5 million kilometers (940,000 miles) away from Earth. L2 is one of five points in the solar system where gravitational forces allow an object to remain in a fixed position relative to Earth, and will keep Webb accessible for operations and communications.

As Earth orbits the Sun, its gravity will drag Webb along with it, keeping it in this optimal location. It will take a full month for Webb to reach its new home beyond the Moon.

Open Design

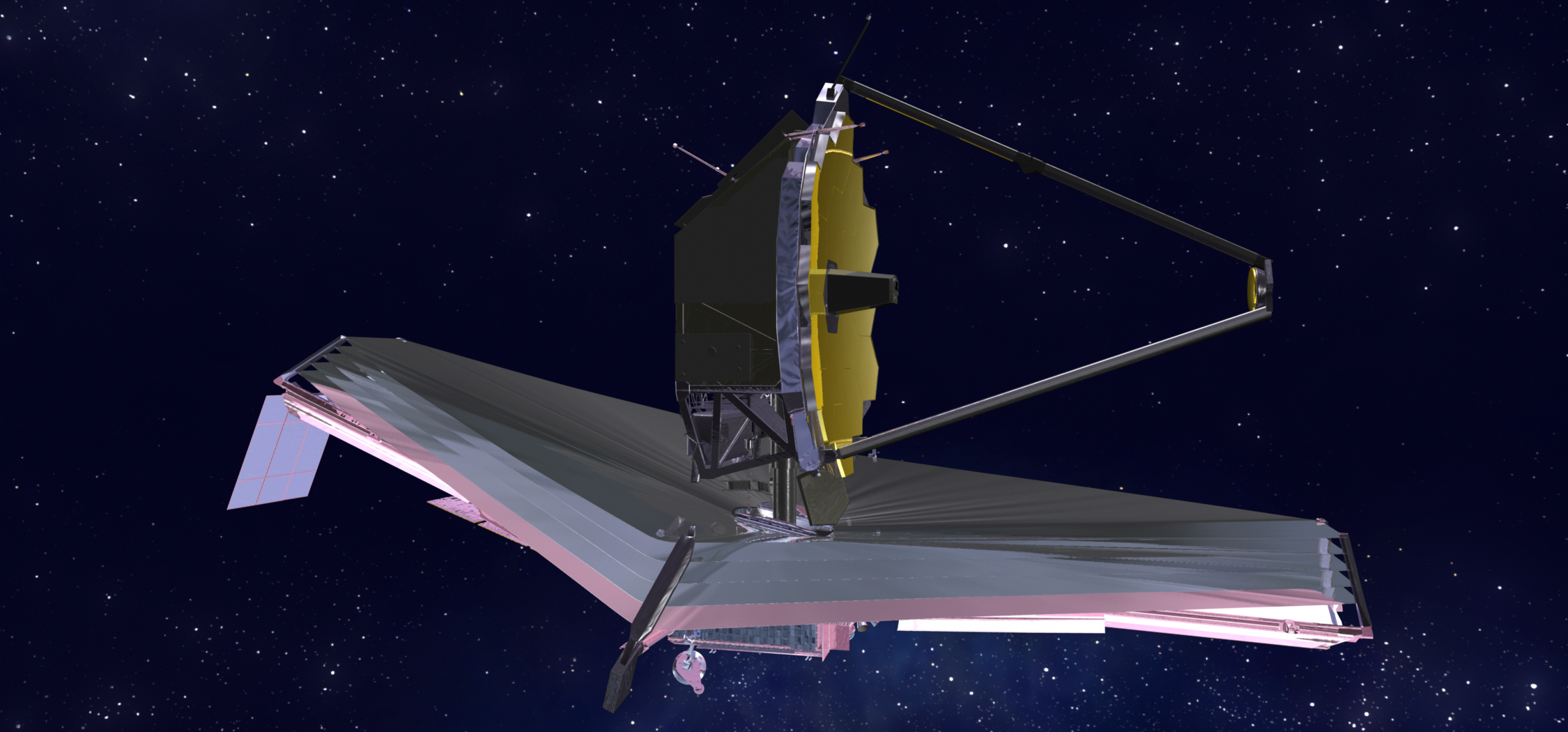

The need to keep Webb cold affects its design dramatically. For instance, the telescope’s odd appearance is the result of it not being enclosed in a tube. Telescopes are usually enclosed in a tube or a dome to block out nearby, unwanted light and radiation. Webb needs to be open to space to keep itself cool enough for its infrared detectors to work properly.

A tube would both radiate infrared and trap too much heat inside the telescope, while the open design allows the heat to pour harmlessly off into space. So rather than use a tube, Webb stops unwanted visible and infrared light with its giant sunshield and baffles, which are small, dark barriers that block light at strategically placed points.

The open design is the only way to cool Webb to the right temperatures and while maintaining its large size. If the Webb telescope relied mainly on coolant like other infrared telescopes, it would need many tons of coolant and its life would be significantly shorter, since once the coolant ran out the telescope would be unusable.

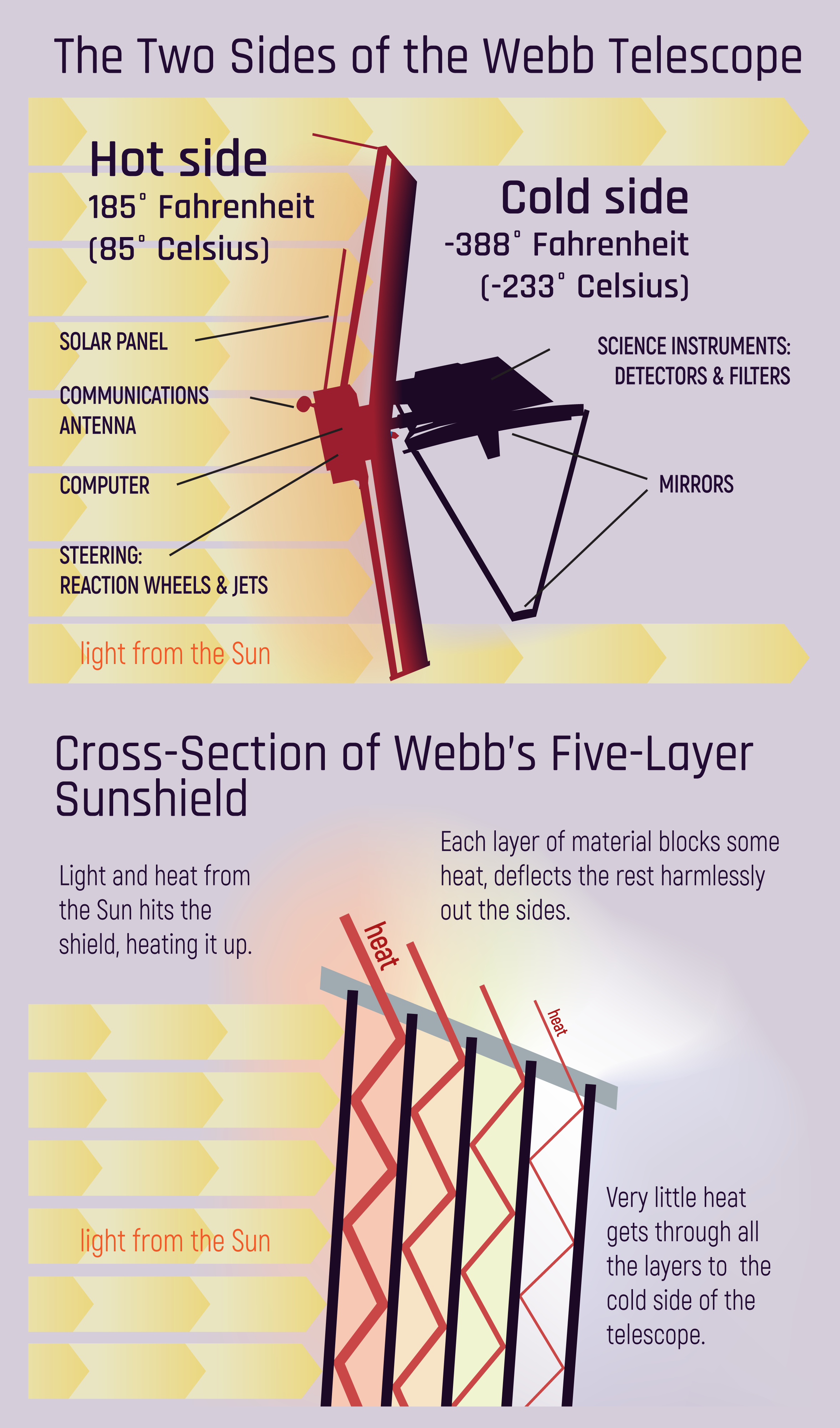

Hot and Cold Sides

PLACEHOLDER IMAGE FOR:

Two Sides of the Webb Telescope

IMAGE LOCATION:

https://webbtelescope.org/contents/media/images/4202-Image

Webb has two sections—a hot side and a cold side, divided by its sunshield. On the hot side of the sunshield, the region exposed to sunlight, parts of Webb will reach temperatures near boiling, as high as 358 kelvins (85 degrees Celsius or 185 degrees Fahrenheit). This is where Webb’s ambient-temperature equipment, like its solar panel, antennae, computer, gyroscopes, and navigational jets are kept. The warm side of the telescope is, overall, where the electronics and navigation system resides.

On the cold side, Webb will be about 40 kelvins (-233 degrees Celsius or -388 degrees Fahrenheit). In contrast, the coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth, at the Russian Vostok station in Antarctica, was -89 degrees Celsius (-129 degrees Fahrenheit)—far too toasty for Webb. The cold side of the sunshield is where the science happens. It contains the parts ofWebb most sensitive to infrared radiation: its microshutter array, mirror and mirror actuators, filter wheels, and, of course, the infrared detectors.

The infrared detectors in most of Webb’s instruments need temperatures of about 40 kelvins to operate correctly. The detectors themselves give off heat when they are in use, so operators will have to read the detectors continuously rather than periodically to continuously keep them at a stable temperature.

Even more dramatic cooling goes on around the camera and spectrograph in the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). MIRI sees farther into the infrared than the other instruments, which means it has to be kept spectacularly cold. Webb boasts a two-stage cryocooler that works like the world’s most effective refrigerator, pumping a warmth-absorbing gas through the instrument. The first stage brings MIRI’s temperature down to 18 kelvins, and the second stage brings the MIRI detectors to 7 kelvins—that’s just 7 degrees above absolute zero, the theoretical temperature at which all motion freezes, even the movement of atoms.