Contents

- What Were the First Stars Like?

- Short answer: We don’t really know.

- What were the first stars made of?

- Short answer: Hydrogen and helium (and tiny amounts of lithium). That’s it.

- How massive were the first stars?

- Short answer: Probably really big, but maybe not.

- How hot and bright were the first stars?

- Short answer: Probably a lot hotter and brighter than the Sun.

- What happened to the first stars?

- Short answer: They burned out, exploded, or collapsed.

- Will we ever be able to see the first stars directly?

- Short answer: Maybe, if we are very lucky.

What Were the First Stars Like?

Short answer: We don’t really know.

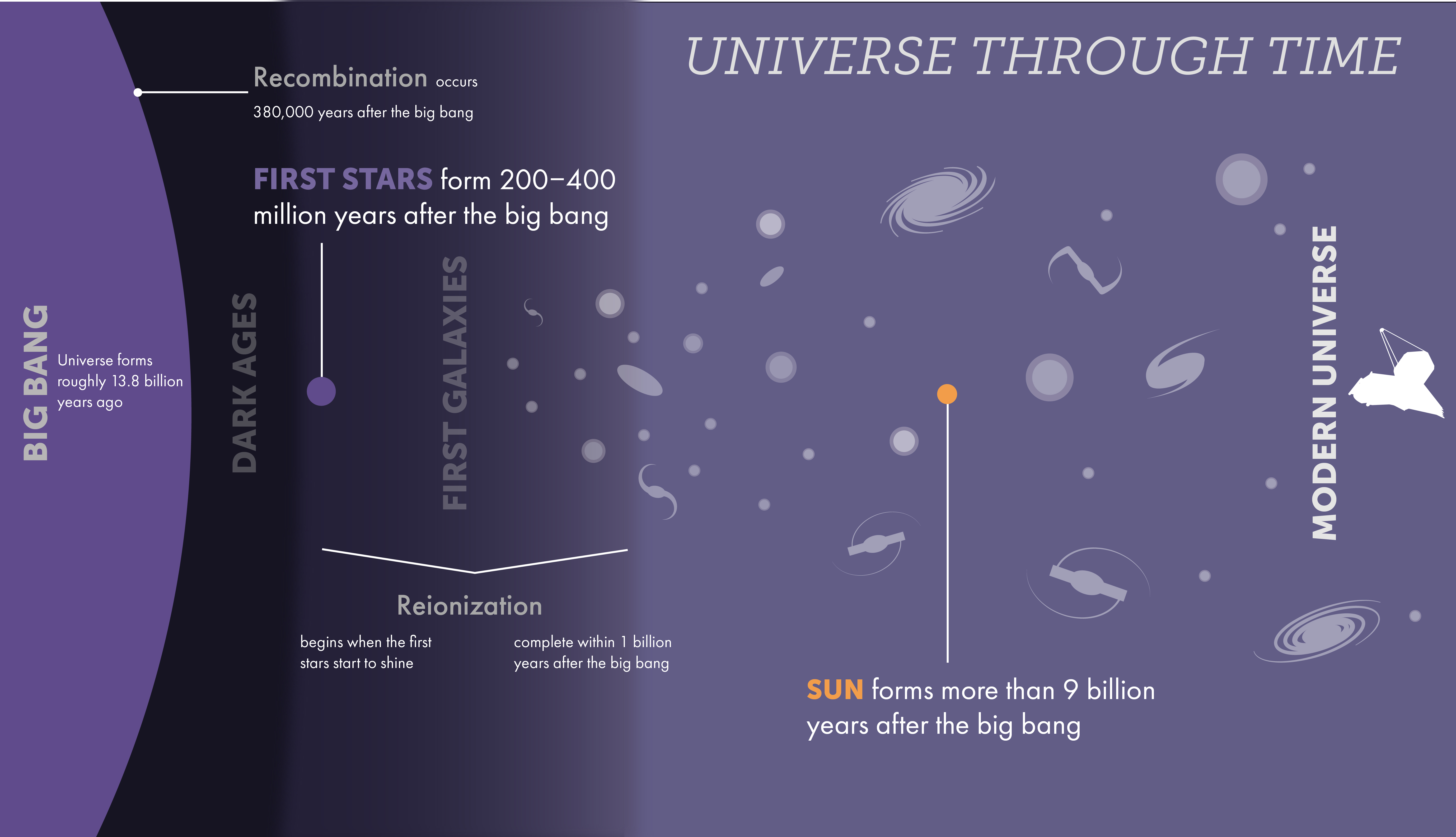

Four hundred thousand years after the big bang, the universe was a cold, dark fog of hydrogen and helium atoms. Less than 400 million years later, it had begun to shine with the light of infant galaxies. Sometime in between, the first stars must have formed.

What were these stars made of? How big and bright were they? How long did they live, and what happened to them when they died? Do any still exist?

The fact is, no one really knows exactly what the first stars were like. Not even the most powerful telescopes operating today—space telescopes like Hubble, Spitzer, and Chandra, and ground-based telescopes like Keck and ALMA—have been able to detect them. But we do have some ideas.

What were the first stars made of?

Short answer: Hydrogen and helium (and tiny amounts of lithium). That’s it.

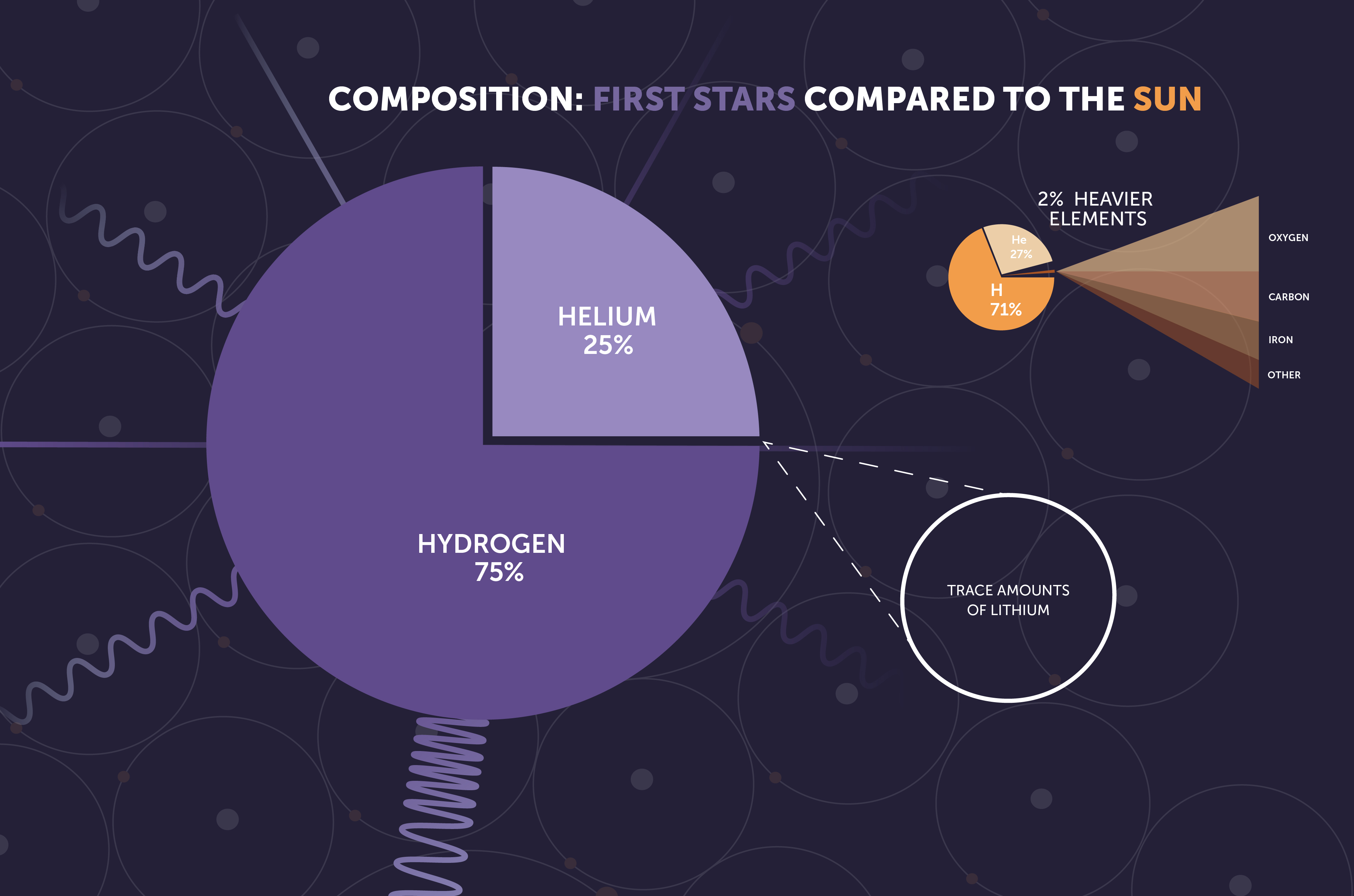

Astronomers know that the first stars, officially known as Population III stars, must have been made almost solely of hydrogen and helium—the elements that formed as a direct result of the big bang. They would have contained none of the heavier elements like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and iron that are found in stars shining today. In other words, Population III stars were metal-free. (Astronomers refer to any element heavier than helium as a metal.)

This might seem like a bold statement given that we have not actually observed any metal-free stars. But as with all scientific claims, it is based on evidence and reasoning: We know from observations, experiments, and calculations that only hydrogen and helium (and minute amounts of lithium) were formed directly after the big bang. The only way that heavier elements like carbon, oxygen, and iron can form is by fusion of lighter elements in the cores of stars. So until the first stars began to form them, none of these elements existed in the universe. The first stars must have been metal-free.

How massive were the first stars?

Short answer: Probably really big, but maybe not.

Although astronomers are quite certain what the first stars were made of, they are less sure how massive they were.

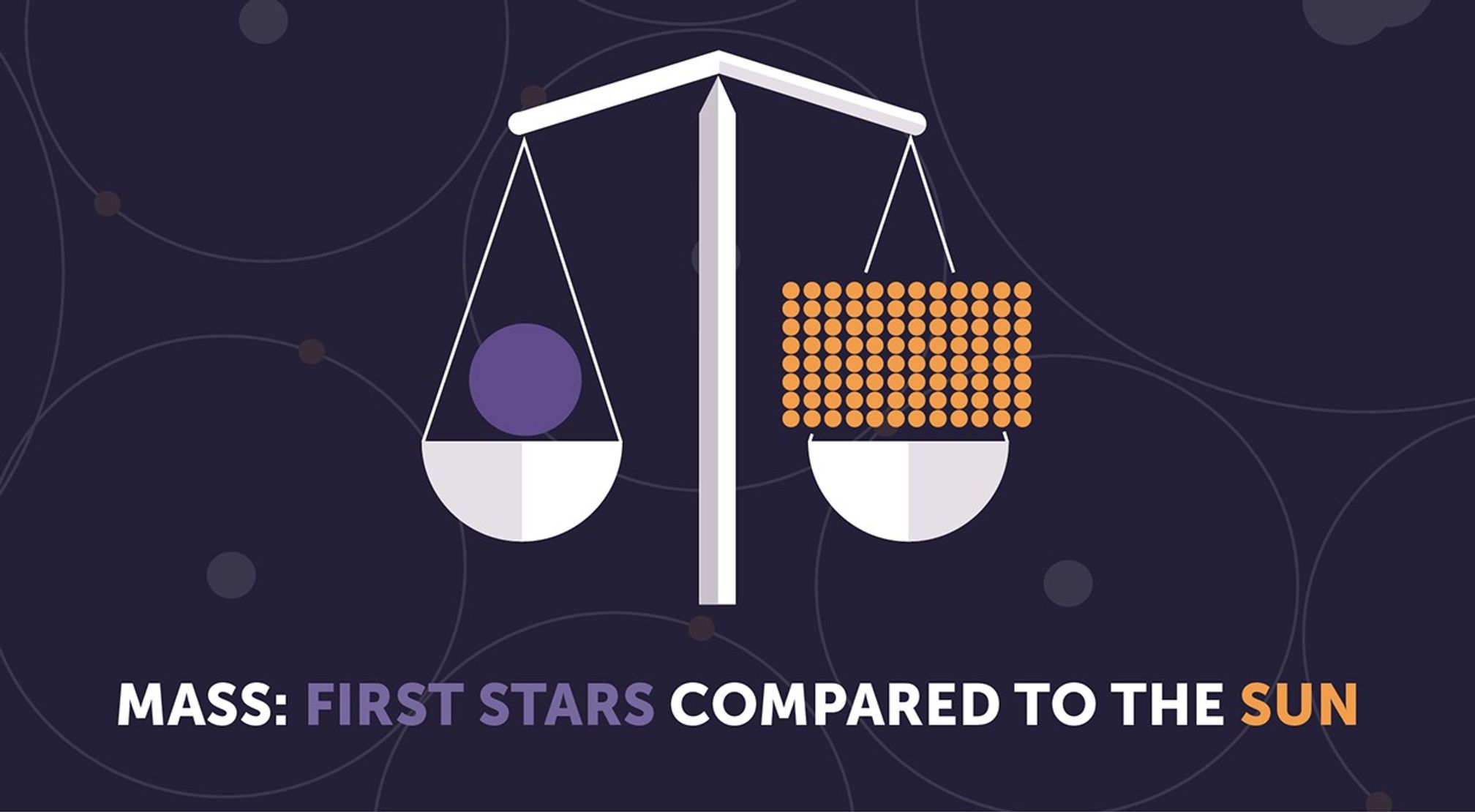

Strangely, one constraint on the mass of metal-free stars comes from what we don’t see: Because we haven’t observed any metal-free stars, we are fairly certain that there could not have been many small ones. Small stars like the Sun last for billions of years. If small Population III stars were common, we should have detected some by now.

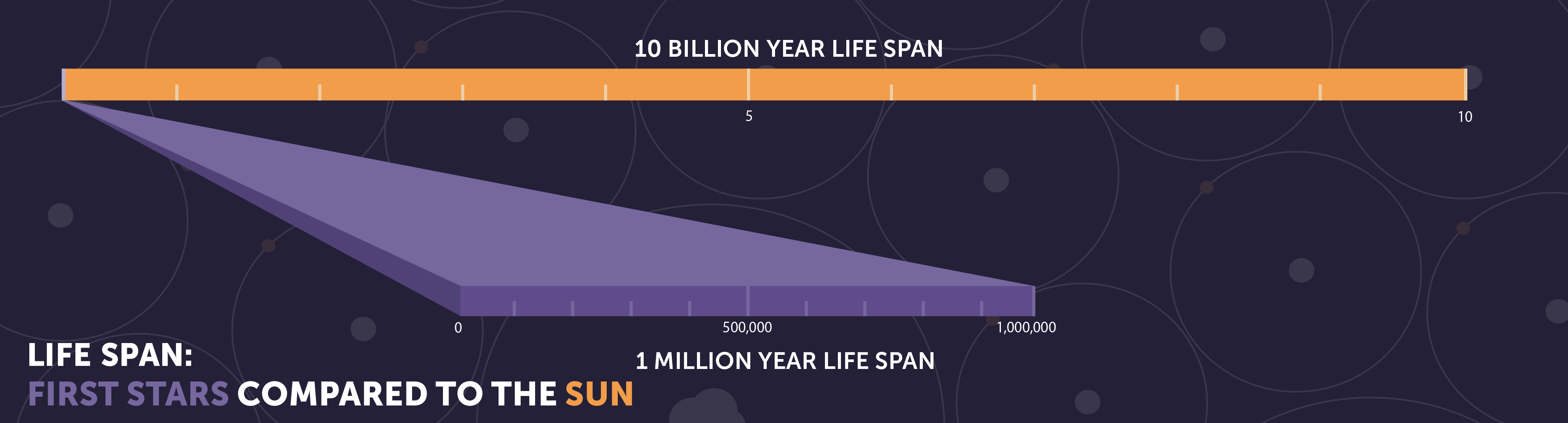

Extremely large stars, on the other hand, burn their fuel very quickly. A star 60 times the mass of the Sun lasts less than one million years. If all of the first generation of stars were extremely massive, none would still exist, and it would make sense that we have not seen any.

Additional evidence for the size of the first stars comes from computer models that simulate how large clouds of hydrogen, helium, and dark matter could cool and collapse to form stars in the early universe. These simulations also suggest that it takes a lot more matter to form a metal-free star than one with even a small proportion of metals. Combined with the fact that we have not seen any metal-free stars, this leads many astronomers to think that the first stars were probably very massive, perhaps ranging between about 10 and 300 times the mass of the Sun.

How hot and bright were the first stars?

Short answer: Probably a lot hotter and brighter than the Sun.

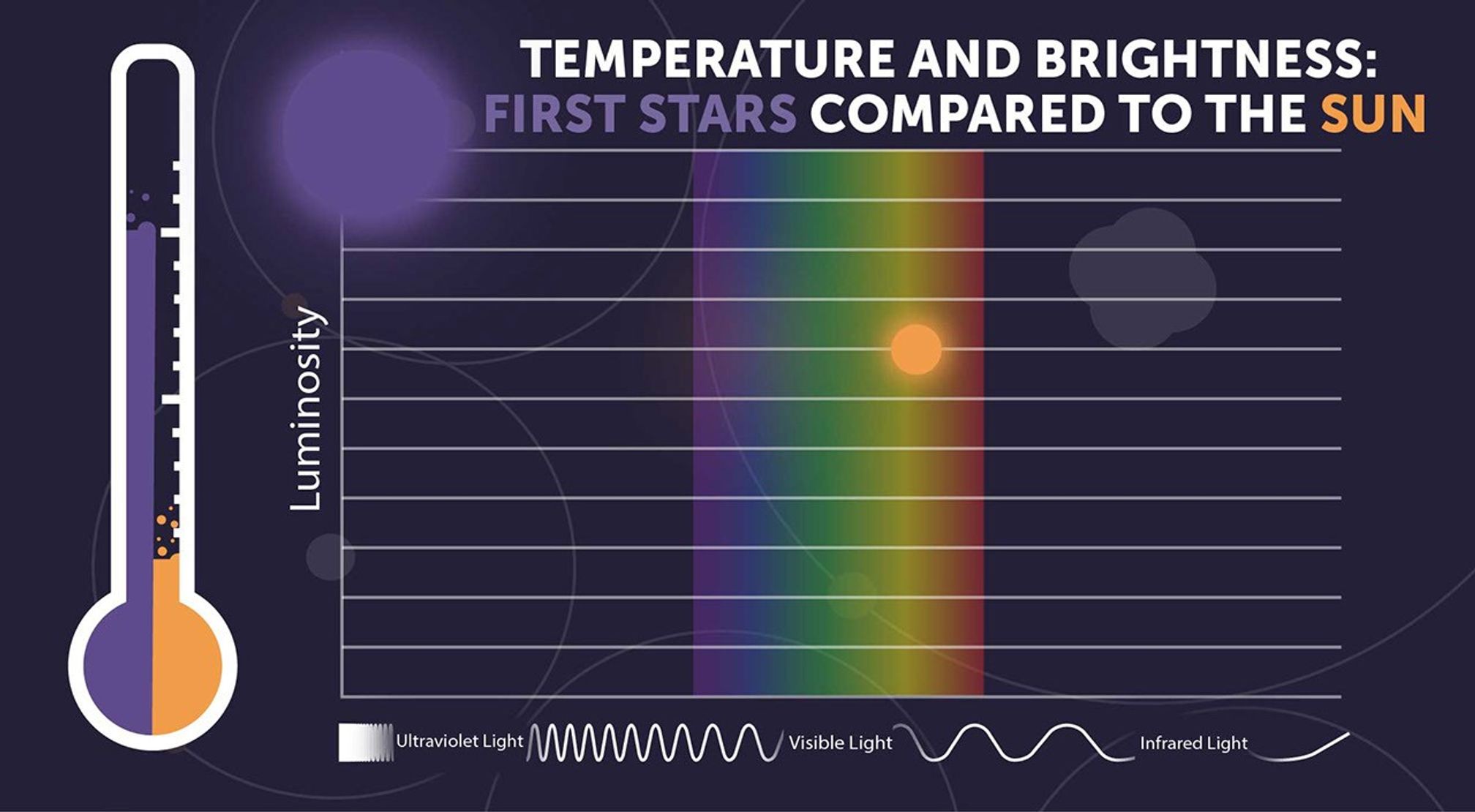

The temperature and brightness of a star is directly related to its mass: The more massive the star is, the hotter and brighter it is. If the first stars were very massive, they also must have been extremely hot and bright. A star 100 times the mass of the Sun, for example, would have a surface temperature around 100,000 kelvins and would shine with the energy of 1 millions Suns.

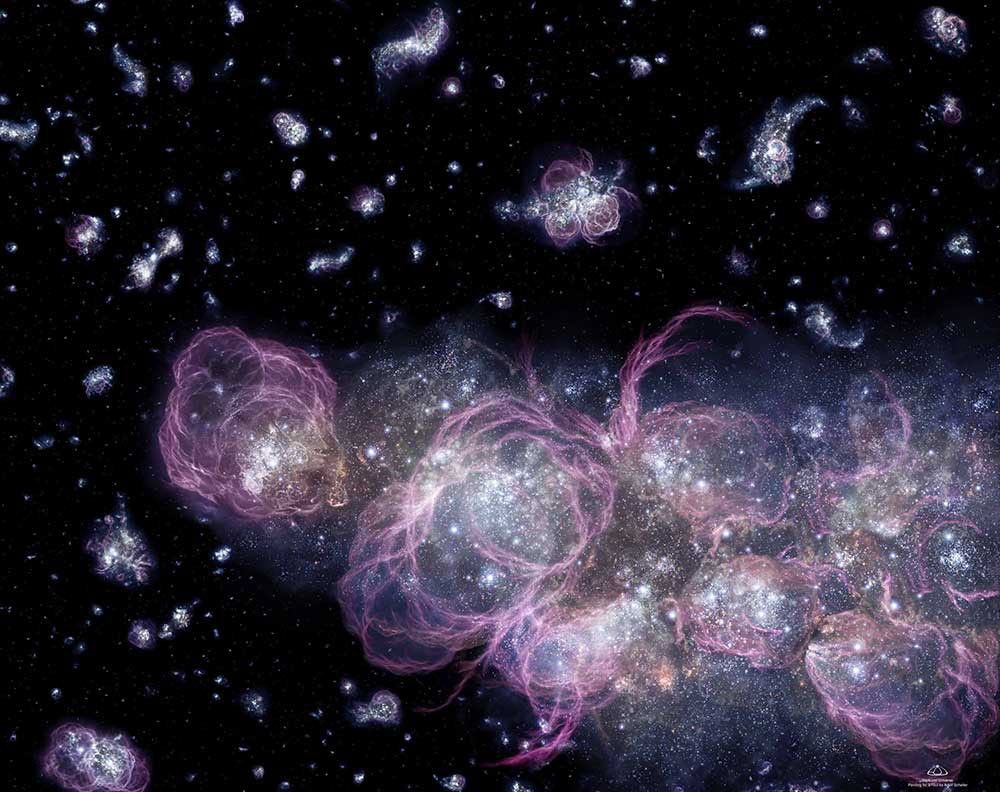

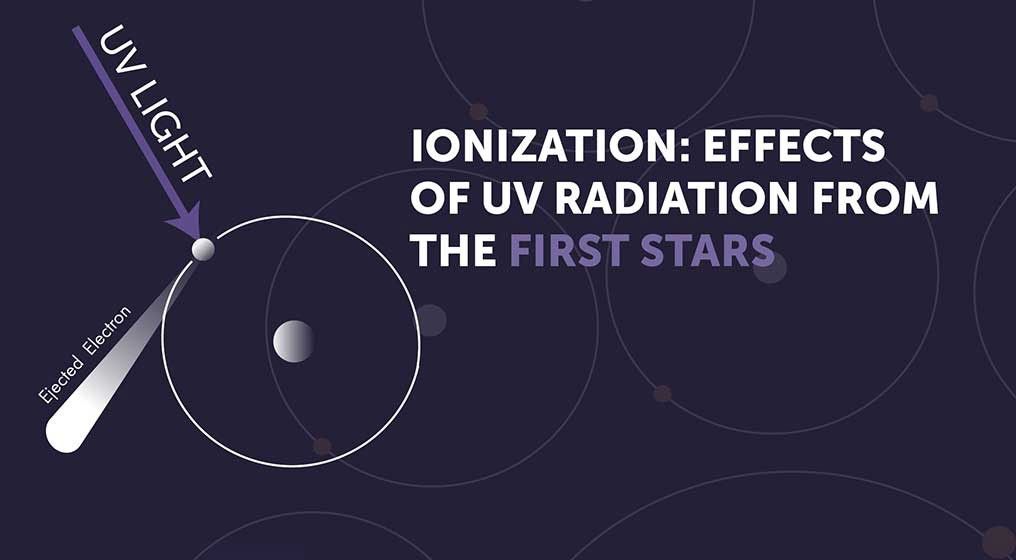

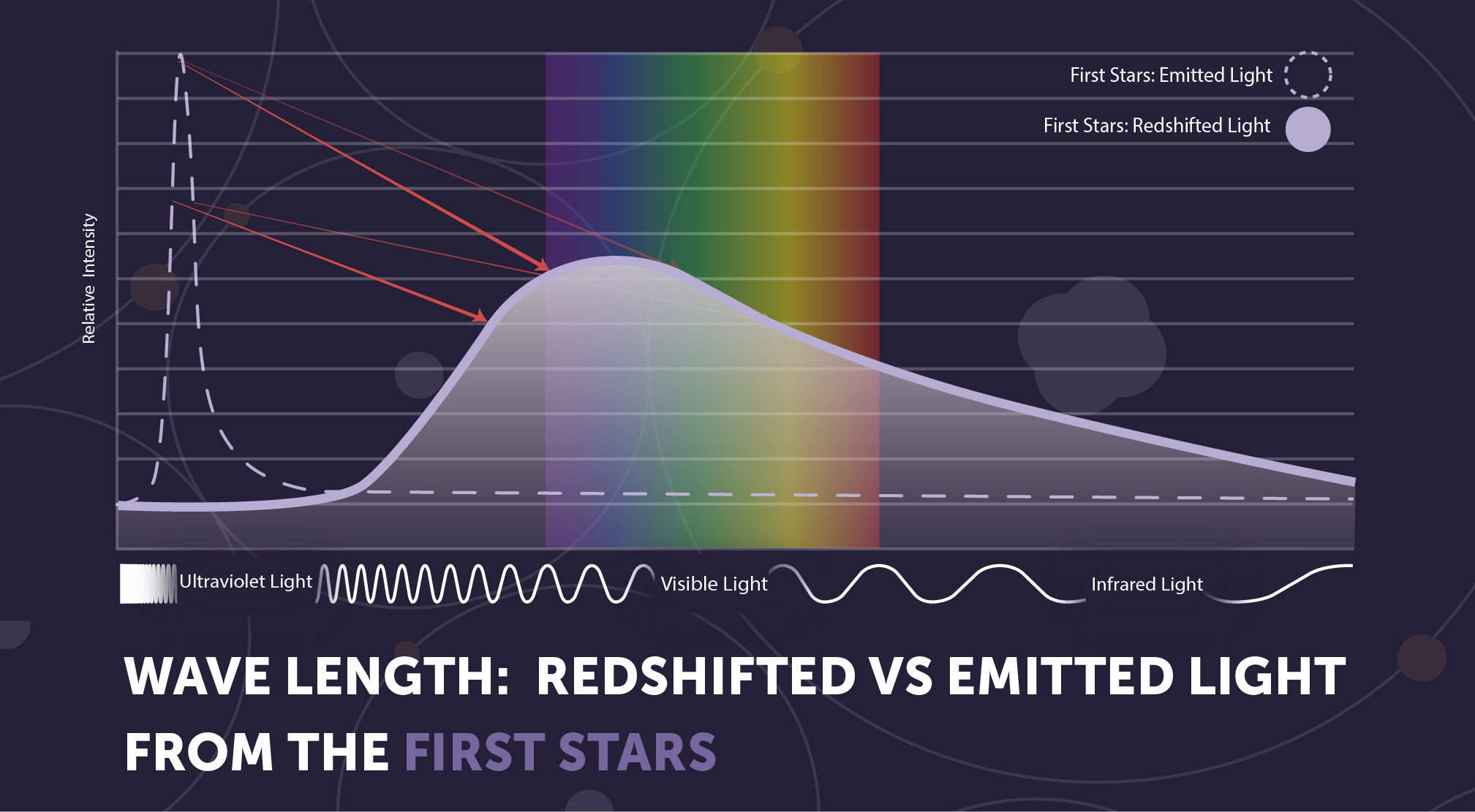

If the first stars were this hot, they must have been giving off enormous amounts of high-energy radiation. While the Sun emits most of its energy in the optical part of the electromagnetic spectrum—the visible light that we are all familiar with—almost all of the light emitted by a star with a temperature of 100,000 kelvins would be in the form of ultraviolet light, which is invisible to human eyes. Astronomers think that it was the ultraviolet radiation emitted by the first stars that began to ionize the universe, lifting the fog of opaque neutral hydrogen that filled the universe during the so-called Dark Ages.

What happened to the first stars?

Short answer: They burned out, exploded, or collapsed.

Based on what we know about physics, we know that if any of the earliest stars were smaller than 0.9 times the mass of the Sun, they should still be shining today. But if they were very massive, they would have had extremely short lifetimes, burning up their fuel quickly and dying within a few million years of forming. What exactly happened to them would depend on their mass.

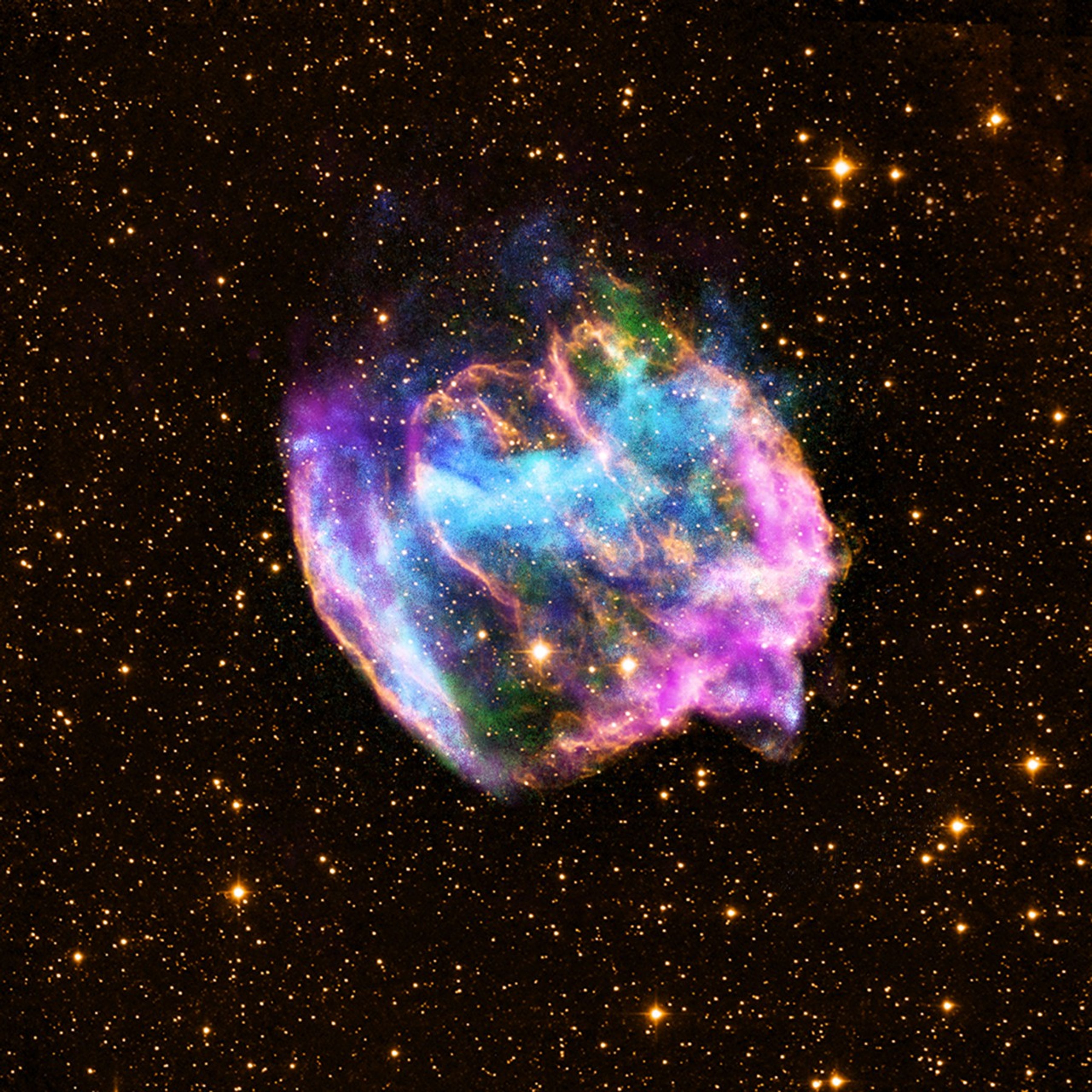

Computer models show that stars greater than 10 and less than about 140 times the mass of the Sun would have ended in supernova explosions, the metals that formed in their cores blown out and dispersed into the surrounding universe. The remains of these stars would have collapsed to form neutron stars or black holes.

Larger metal-free stars, up to about 300 solar masses, might have exploded in a strange type of supernova. These explosion would have blasted every bit of the star out in all directions, leaving nothing behind—no neutron star or black hole. The only signs of these stars would be found in the chemical composition of later stars that formed from their exploded remains.

Even larger metal-free stars would have collapsed directly to form black holes, taking everything with them without even exploding first. While these stars would not have contributed matter to form new stars, they may have influenced galaxies in other ways. It may be that these black holes were the seeds of supermassive black holes found at the centers of galaxies today.

Will we ever be able to see the first stars directly?

Short answer: Maybe, if we are very lucky.

So far, the only real evidence we have for the first stars is in the tracks they’ve left behind: the metals they formed that we see in later generations of stars; the effects of their ionizing radiation on the primordial gas in the universe; and perhaps their remnant black holes. If the first stars were massive and short-lived, any that existed nearby are long gone.

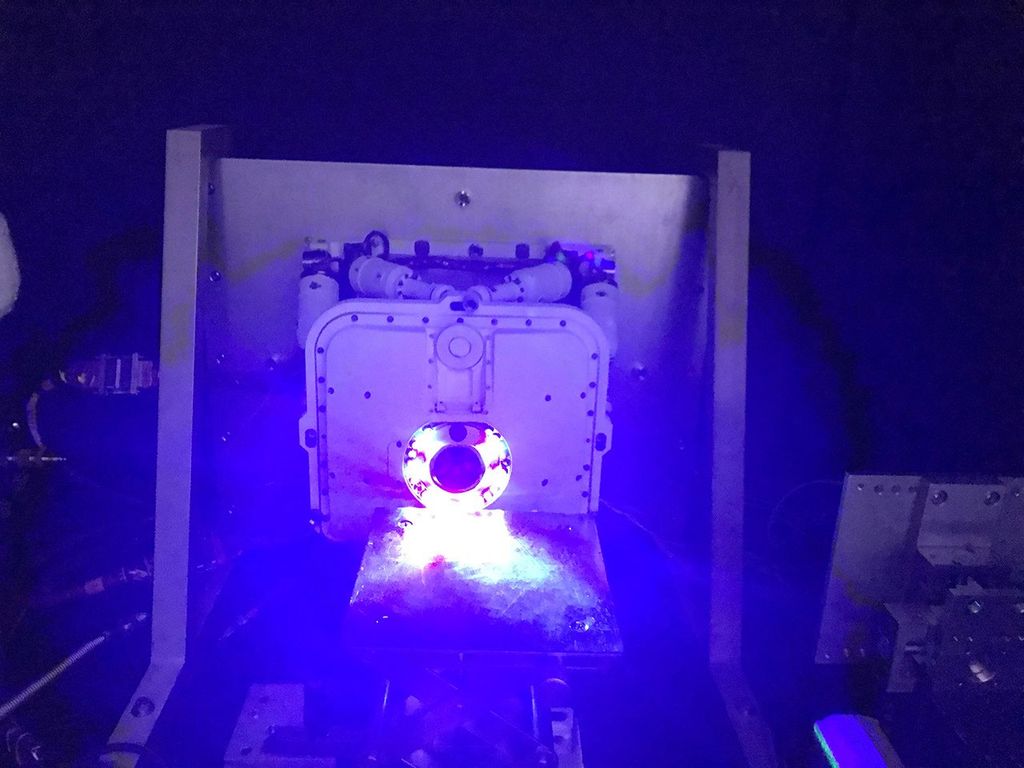

Even if they no longer exist, it is theoretically still possible to see them. Telescopes like Hubble allow us to see billions of light-years away and thus billions of years back in time. The James Webb Space Telescope gives us the advantage of being able to detect even dimmer infrared light. Although most of the light given off the first massive stars was in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum when it was emitted, the universe has expanded so much since then that much of it is now in the visible and infrared. (Hubble also covers this portion of the spectrum, but Webb’s mirror is much larger, allowing it to detect much lower levels of light.)

But as powerful as Webb is, it will still be difficult to see individual stars that far back in time. Although these stars were extremely bright, they are so far away that very little of their light actually reaches us.

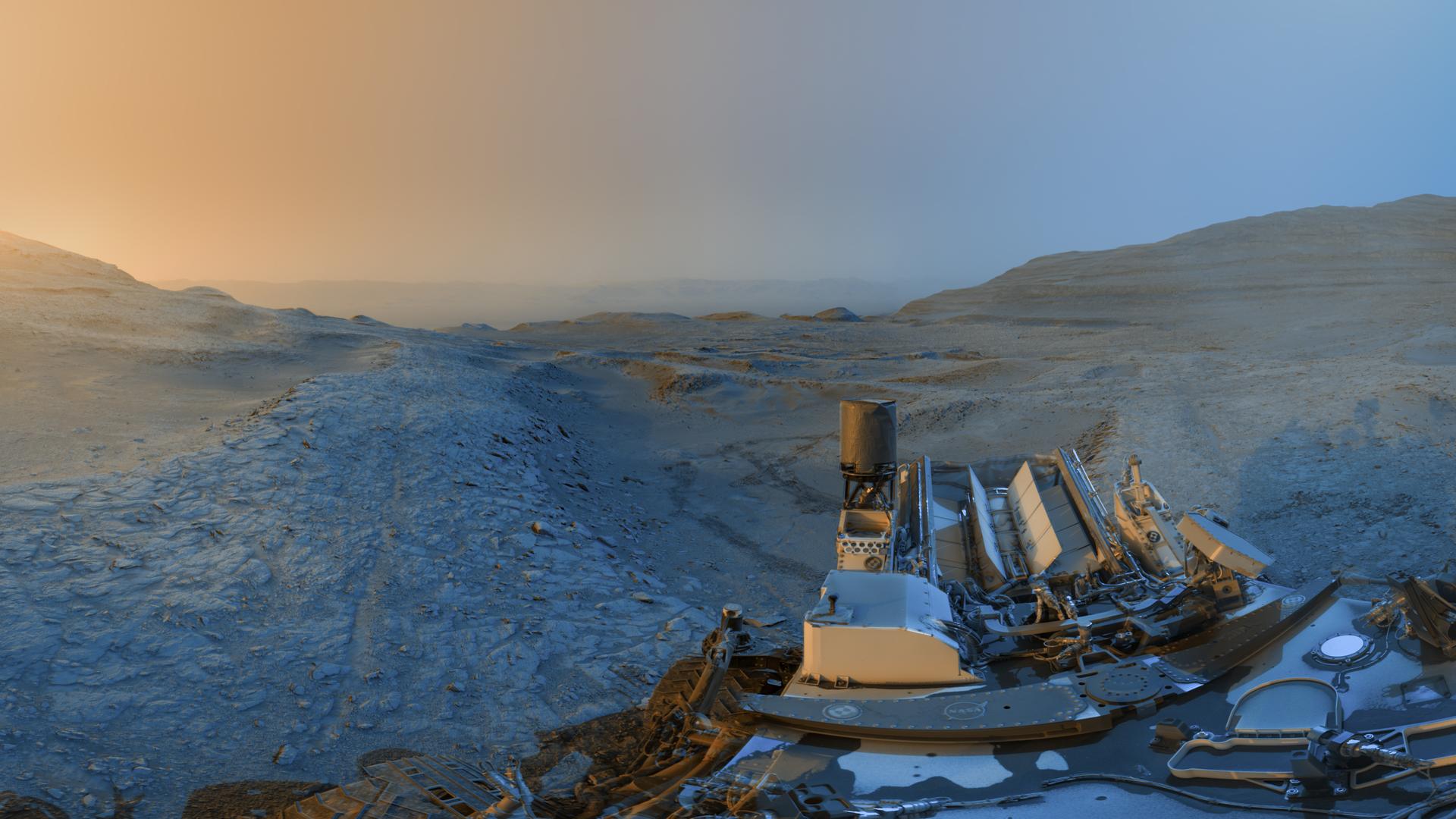

We will almost certainly be able to see ancient galaxies that contain first-generation stars, and will be able to make some inferences about individual stars from the light coming from the galaxy as a whole. But galaxies contain hundreds of thousands to millions of stars, each at a different point in its life cycle. Even if some of the stars are metal-free, new stars will have begun forming from the metallic stardust scattered through the galaxy.

Making things even more difficult, the fog of neutral hydrogen gas that filled the universe when the very first stars were forming would have absorbed their ultraviolet light. Until the ultraviolet radiation ionized enough atoms to allow light to pass through, our view of the first stars would be blocked.

Even so, we might get lucky. We may be able to see individual stars with the help of a strong gravitational lens: a cluster of galaxies that forms a natural magnifying glass in just the right place in the sky. Maybe we will catch the bright explosion of a Population III star at the very end of its life. Maybe some of the first stars were very small and are still shining, visible in nearby galaxies—perhaps even in our own Milky Way.