Engineering Challenge

The James Webb Space Telescope's primary science comes from infrared light, which is essentially heat energy. To detect the extremely faint heat signals of astronomical objects that are incredibly far away, the telescope itself has to be very cold and stable. This means we not only have to protect Webb from external sources of light and heat (like the sun and the earth), but we also have to make all the telescope elements themselves very cold so they don't emit their own heat energy that could swamp the sensitive instruments. The temperature also must be kept constant so that materials aren't shrinking and expanding, which would throw off the precise alignment of the optics.

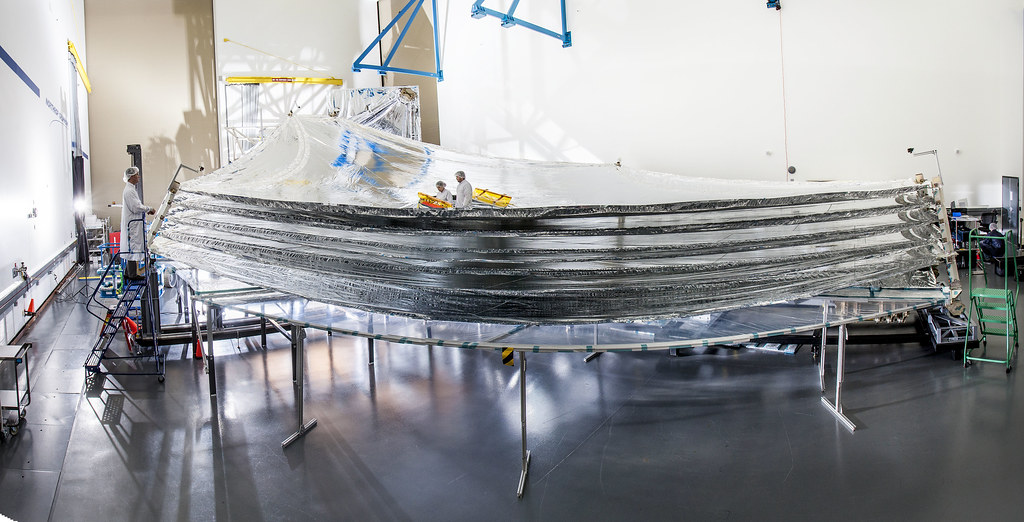

Five Layer Sunshield

To accomplish all of this, Webb deployed a tennis-court sized Sunshield made of five thin layers of Kapton E with aluminum and doped-silicon coatings to reflect the sun's heat back into space. The Kapton is a commercially available polyimide film from Dupont, while the coatings were applied to a specialized Webb specification.

Material Make-Up

Each layer is coated with aluminum, and the sun-facing side of the two hottest layers (designated Layer 1 and Layer 2) also have a "doped-silicon" (or treated silicon) coating to reflect the sun's heat back into space. The sunshield is a critical part of the Webb telescope because the infrared cameras and instruments aboard must be kept very cold and out of the sun's heat and light to function properly.

Kapton is a polyimide film that was developed by DuPont in the late 1960s. It has high heat-resistance and remains stable across a wide range of temperatures from minus 269 to plus 400 Celsius (minus 452 to plus 752 degrees Fahrenheit). It does not melt or burn at the highest of these temperatures. On Earth, Kapton polyimide film can be used in a variety of electrical and electronic insulation applications.

The sunshield layers are also coated with aluminum and doped-silicon for their optical properties and longevity in the space environment. Doping is a process where a small amount of another material is mixed in during the Silicon coating process so that the coating is electrically conductive. The coating needs to be electrically conductive so that the Membranes are electrically grounded to the rest of JWST and do not build up a static electric charge across their surface. Silicon has a high emissivity, which means it emits the most heat and light and acts to block the sun's heat from reaching the infrared instruments that are located underneath it. The highly-reflective aluminum surfaces also bounce the remaining energy out of the gaps at the sunshield layer's edges. (Fun fact: the pink hue of the lower side of the sunshield is actually due to the coating.)

The size, position, spacing and shape of the Sunshield layers are also very important - more information on these aspects can be found on our sunshield page.