Webb Project History

Even before the Hubble Space Telescope’s launch in 1990, astronomers began posing the question: What is the next step after Hubble?

In September 1989, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and NASA co-hosted the Next Generation Space Telescope Workshop at STScI, bringing together more than 130 astronomers and engineers. The group proposed that NASA investigate the feasibility of a 10-meter, passively cooled, near-infrared telescope in a high-Earth orbit or a 16-meter telescope based on the Moon to study galaxies at high redshift.

In 1996, an 18-member committee led by astronomer Alan Dressler formally recommended that NASA develop a space telescope that would view the heavens in infrared light—the wavelength band that enables astronomers to see through dust and gas clouds and extends humanity’s vision farther out into space and back in time. It would have a mirror with a diameter of more than four meters, and operate in an orbit well beyond Earth’s moon.

Three teams made up of scientists and engineers from the private and public sectors met to determine whether NASA could realize the committee’s vision. All three came to the conclusion that the proposed telescope would work. NASA agreed in 1997 to fund additional studies to refine the technical and financial requirements for building the telescope. By 2002, the agency had selected the teams to build the instruments and the group of astronomers who would provide construction guidance. Also in 2002, the telescope was formally named the James Webb Space Telescope, after the NASA administrator who led the development of the Apollo program.

From Vision to Reality

Engineers and astronomers innovated new ways to meet the Webb telescope’s scientific demands, as well as a mission at an unserviceable distance from Earth. Unlike Hubble, astronauts will not be able to repair and upgrade the telescope.

Construction on Webb began in 2004. In 2005, the European Space Agency’s Centre Spatial Guyanais (CSG) spaceport in French Guiana was chosen as the launch site, and an Ariane 5 rocket as the launch vehicle. By 2011, all 18 mirror segments were finished and proven through testing to meet required specifications.

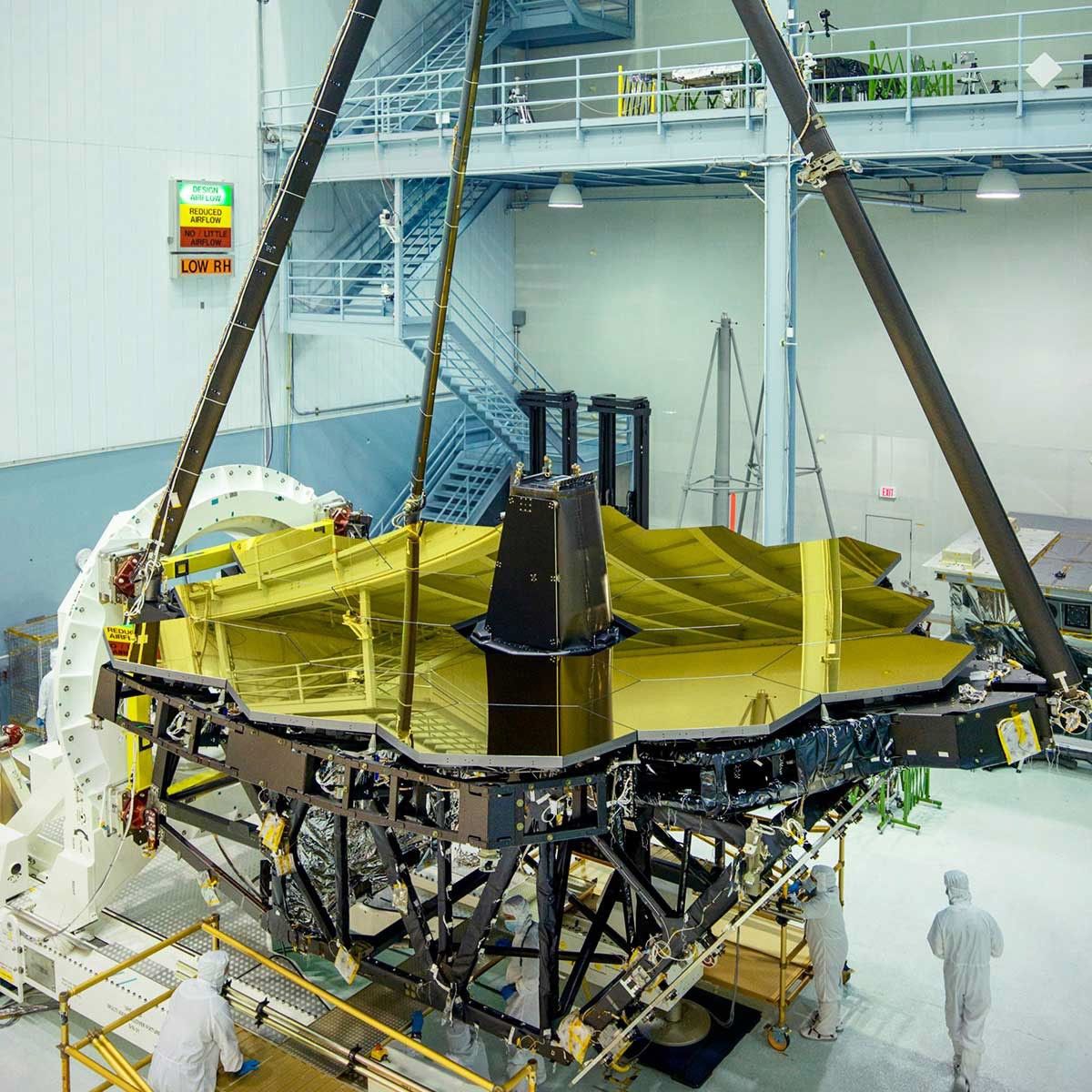

Between 2012 and 2013, Webb’s individual pieces, constructed in a variety of locations, began to arrive at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. In 2013, construction of the sunshield layers began. From 2013 to 2016, Webb’s science instruments were subjected to numerous tests of extreme temperature and vibration. From late 2015 to early 2016, all 18 of Webb’s individual mirrors were installed on the telescope’s backplane structure to assemble the 6.6 meter (21.7 feet) mirror.

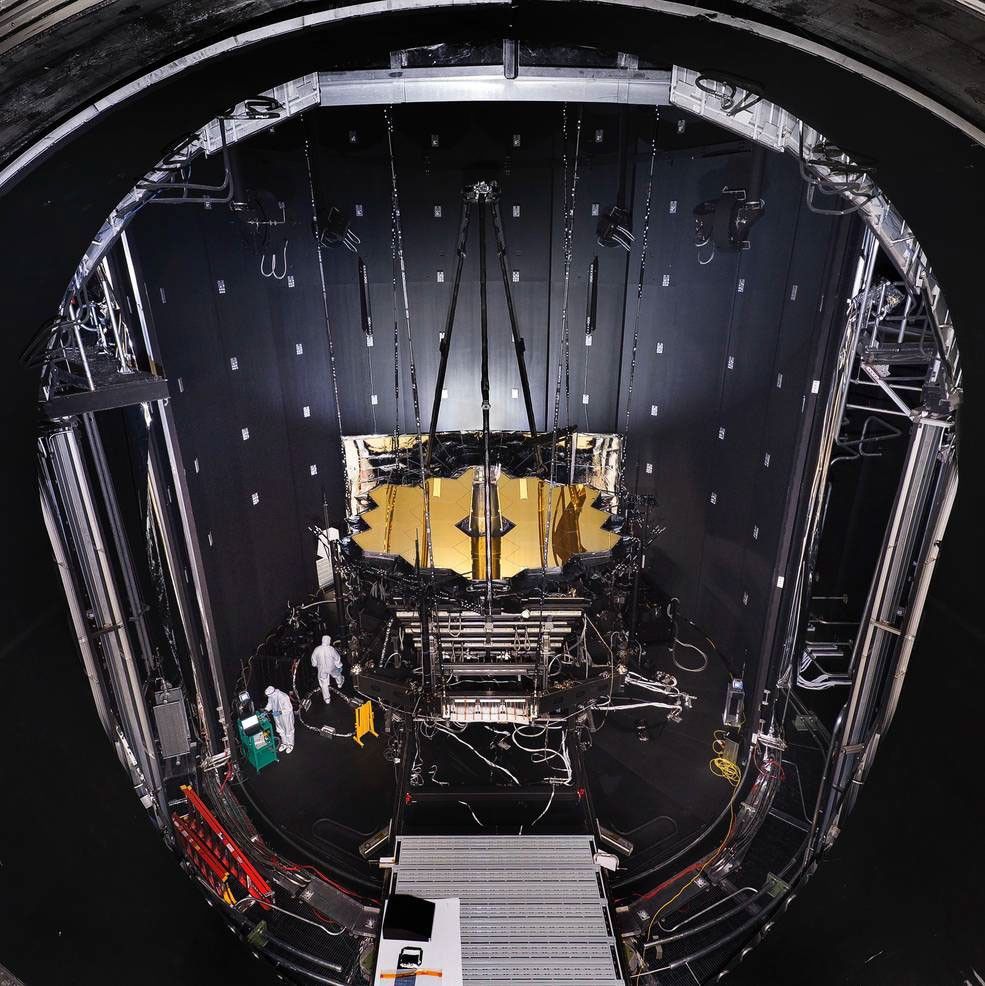

In 2017, the mirrors and science instruments were connected and tested, then shipped to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Additional environmental tests of the coupled telescope and instrument assembly occurred in a giant thermal vacuum chamber at Johnson in 2017, withstanding Hurricane Harvey in late August without a delay in schedule. Final assembly and testing takes place in 2018 and 2019 to ensure that Webb will perform its complex deployment unfolding and scientific mission perfectly once in space, since it will be farther away than humans have ever travelled and will not be able to be serviced. At 7:20 a.m. EST (1220 GMT) on December 25, 2021, Webb launched from CSG.

Webb Project Timeline

1989

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and NASA co-host the Next Generation Space Telescope Workshop at STScI. The focus was the science and technical capabilities of an observatory that would follow the Hubble Space Telescope after it was decommissioned, which was estimated at that time to be 2005.

1995—1996

An STScI committee recommends a significantly larger telescope capable of observing infrared light.

NASA selects Goddard Space Flight Center and STScI to study the feasibility of the Next Generation Space Telescope. Three independent government and aerospace teams determine that such an observatory is feasible.

1997

NASA selects teams from the Goddard Space Flight Center, TRW, and Ball Aerospace to fine-tune the telescope’s technical and financial requirements.

1999

Lockheed Martin, Ball Aerospace, and TRW (also partnering with Kodak and ATK) conduct Phase A mission studies, including preliminary analysis of the design and cost.

2002

Based on two Phase A studies, NASA selects the design of TRW/Ball Aerospace to continue in Phase B detailed design studies, which examine the performance and cost of the chosen design.

The telescope is renamed from the Next Generation Space Telescope to the James Webb Space Telescope.

In Phase B, TRW and Ball are awarded the observatory contract, but changes follow immediately. Northrop Grumman acquires TRW, and works with Ball to develop the observatory during Phases B, C, and D.

NASA selects the flight science working group and the team responsible for developing the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam).

2004

Construction begins on certain telescope parts that require extensive, long-term work—in particular, Webb’s science instruments and the 18 segments of the primary mirror.

2005

NASA approves the use of the European Space Agency’s Ariane 5 rocket to launch Webb into space.

2006

The science instrument teams for the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) pass critical design reviews and initiate construction of the flight instruments. All Webb’s essential technologies are tested successfully under flight conditions.

2007—2008

NASA has the Webb mission reviewed by internal and external groups. The internal preliminary design review and external non-advocate review conclude that the plans and designs have reached the maturity needed for NASA to commit to phases C and D, which entail detailed design, procurement, testing, and assembly of the telescope and observatory components. Construction begins in earnest.

2009

The Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM) structure, built to house Webb'’s four science instruments, arrives at Goddard Space Flight Center for testing.

2010

Webb passes its mission critical design review, which signifies that the integrated observatory will meet all science and engineering requirements for its mission.

2011

Webb’s mirrors are completed. They are beryllium coated in a thin layer of gold, and have passed cryogenic testing, which exposed them to the frigid temperatures they will be subjected to in space.

2012

Goddard Space Flight Center receives two of Webb’s four science instruments, the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) and the Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS), as well as Webb’s Fine Guidance Sensor, from the European and Canadian space agencies. Webb’s secondary mirror and the first three primary mirror segments also arrive at Goddard Space Flight Center from Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp.

Northrop Grumman and partner ATK finish constructing the center section of Webb’s backplane structure, designed to hold the telescope’s primary mirror segments.

2013

The two side “wings” of Webb’s backplane structure are completed by Northrop Grumman and ATK. Webb’s two final science instruments, the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), as well as the remaining primary mirror segments, are delivered to Goddard Space Flight Center.

2014

Manufacturing of the spacecraft parts (such as fuel tanks, gyroscopes, and solar panels) begins.

Cryogenic testing of the Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM), including all four instruments begins, to demonstrate the performance of the instruments as well as the electronics used to communicate with the instruments.

2015—2016

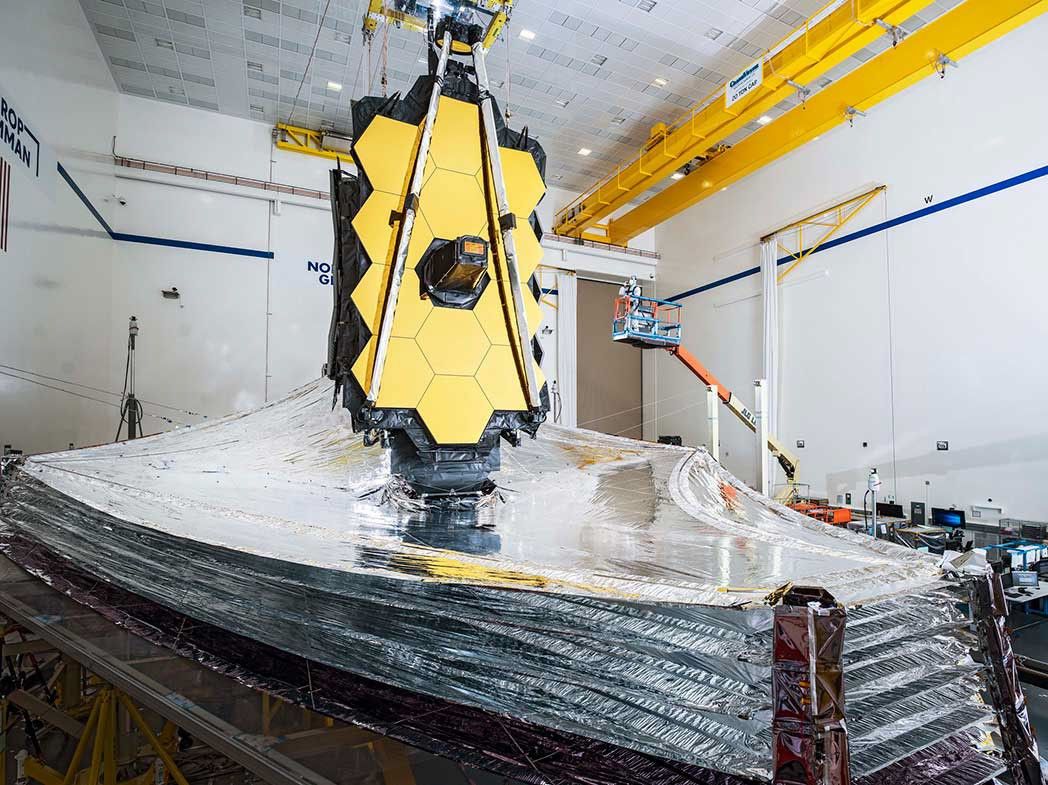

Cryogenic testing of the Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM) is completed. The 18 primary mirror segments are mounted into the backplane, along with the secondary mirror and support struts. The primary and secondary mirrors are integrated with the aft mirrors and the ISIM to create the unit known as the Optical Telescope Element.

2017

The Optical Telescope Element successfully undergoes cryogenic testing in a giant thermal vacuum chamber called Chamber A at Johnson Space Center.

2018

Following successful completion of its final thermal vacuum test, the Optical Telescope Element is delivered to Northrop Grumman in Redondo Beach, California, bringing all of Webb’s flight components under one roof.

The first successful communications tests are run from the Mission Operations Center at STScI to the telescope’s spacecraft on the ground in California.

2019

For the first time, Webb’s spacecraft element—the sunshield and bus—successfully passes acoustic, vibration, and thermal vacuum tests which simulate the rigors of the launch environment as well as the extreme vacuum of space.

Engineers successfully connect the two halves of the Webb telescope—the Optical Telescope Element and the spacecraft—at Northrop Grumman.

2020

Webb is fully folded for the first time and completes final environmental testing to prove it can withstand the shaking and jostling of the launch environment.

Webb’s sunshield is also deployed for the final time on Earth.

2021

Webb is folded and stowed for launch for the final time. STScI announces the selection of Cycle 1 General Observation programs, rounding out the science Webb will conduct during its first year in space.

Webb is shipped to the Guiana Space Centre (Le Centre Spatial Guyanais, CSG) in Kourou, French Guiana, for launch.

December 25, 2021: NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope Launches

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope launched at 7:20 a.m. EST on an Ariane 5 rocket from Europe's Spaceport in French Guiana, South America. Ground teams began receiving telemetry data from Webb about five minutes after launch. The Arianespace Ariane 5 rocket performed as expected, separating from the observatory 27 minutes into the flight. The observatory was released at an altitude of approximately 75 miles (120 kilometers).

Approximately 30 minutes after launch, the Webb Telescope’s unique solar array unfolded, and mission managers confirmed that the array was providing power to the observatory. Within the telescope, there are four state-of-the-art instruments with highly sensitive infrared detectors that will study infrared light from celestial objects at unprecedented resolutions. Webb will deliver its first images at the end of a six-month commissioning period.

The James Webb Space Telescope, built in collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency, will seek the light from the first galaxies in the early universe, study how galaxies and stars change over cosmic time, observe planets orbiting other stars, called exoplanets, and even study our own solar system. Read the release.

2022

July 12, 2022: Webb’s First Images Display the Universe in a New Light

On the evening of July 11, 2022, President Joe Biden unveiled the first full-color image from the James Webb Space Telescope. The near-infrared-light view of galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 is the deepest and sharpest image taken of the distant universe to date. The following morning, full-color images and spectroscopic data for an additional four targets were released, each revealing cosmic features that had never been captured in such detail.

Webb’s first observations demonstrated the telescope’s ability to finely detail the universe through cosmic history. These five images showed the wide array of capabilities of all Webb’s state-of-the-art cameras and spectrographs.

The release of Webb’s first images and spectra kicked off Webb’s science operations, with astronomers around the world beginning to study many different objects, from nearby planets to distant galaxies in the early universe.

Webb's First Images

Mission scientists and engineers demonstrate Webb’s unprecedented capabilities with the telescope’s first collection of data and full-color images, previewing the future of infrared astronomy.

Explore about Webb's First Images