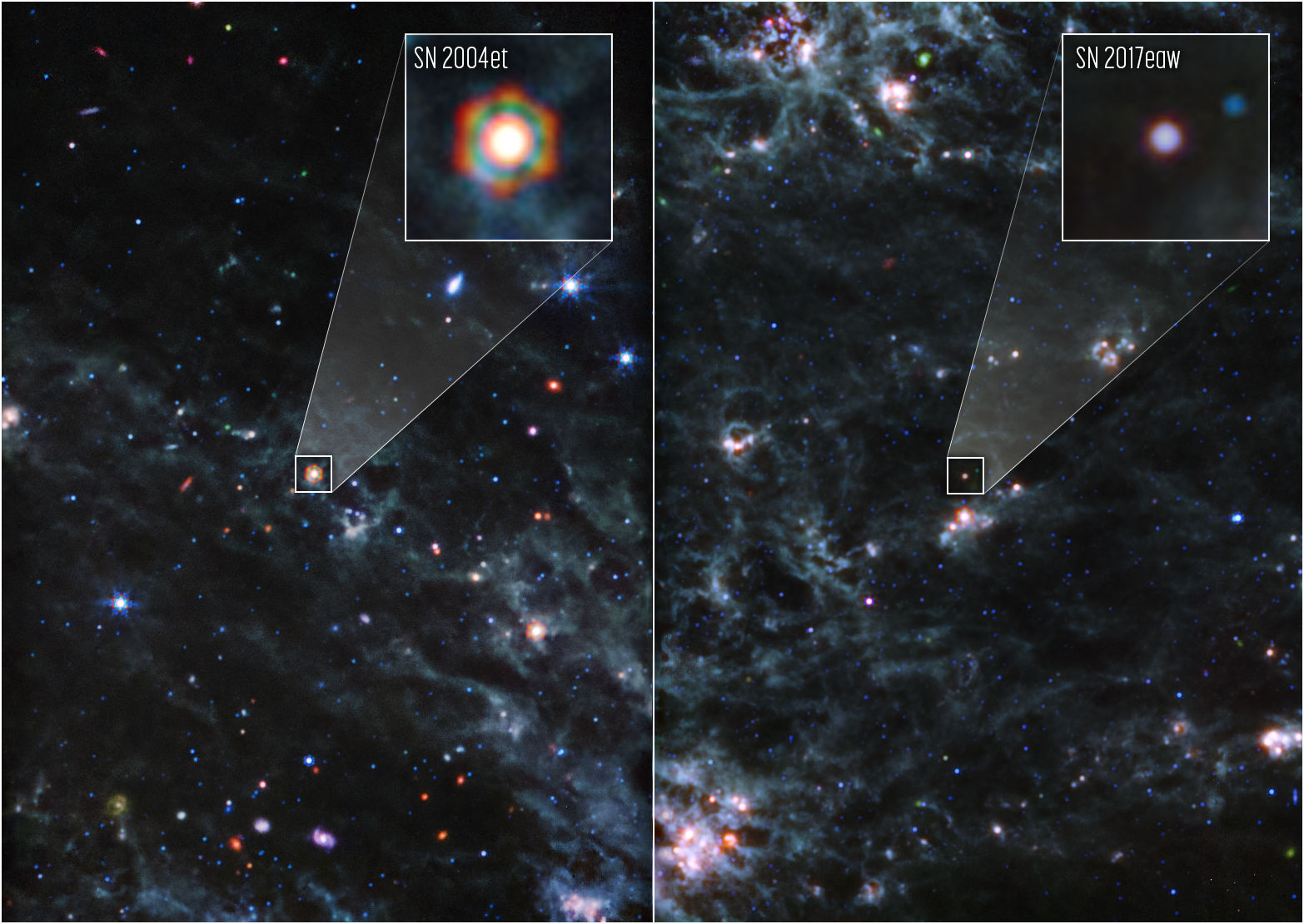

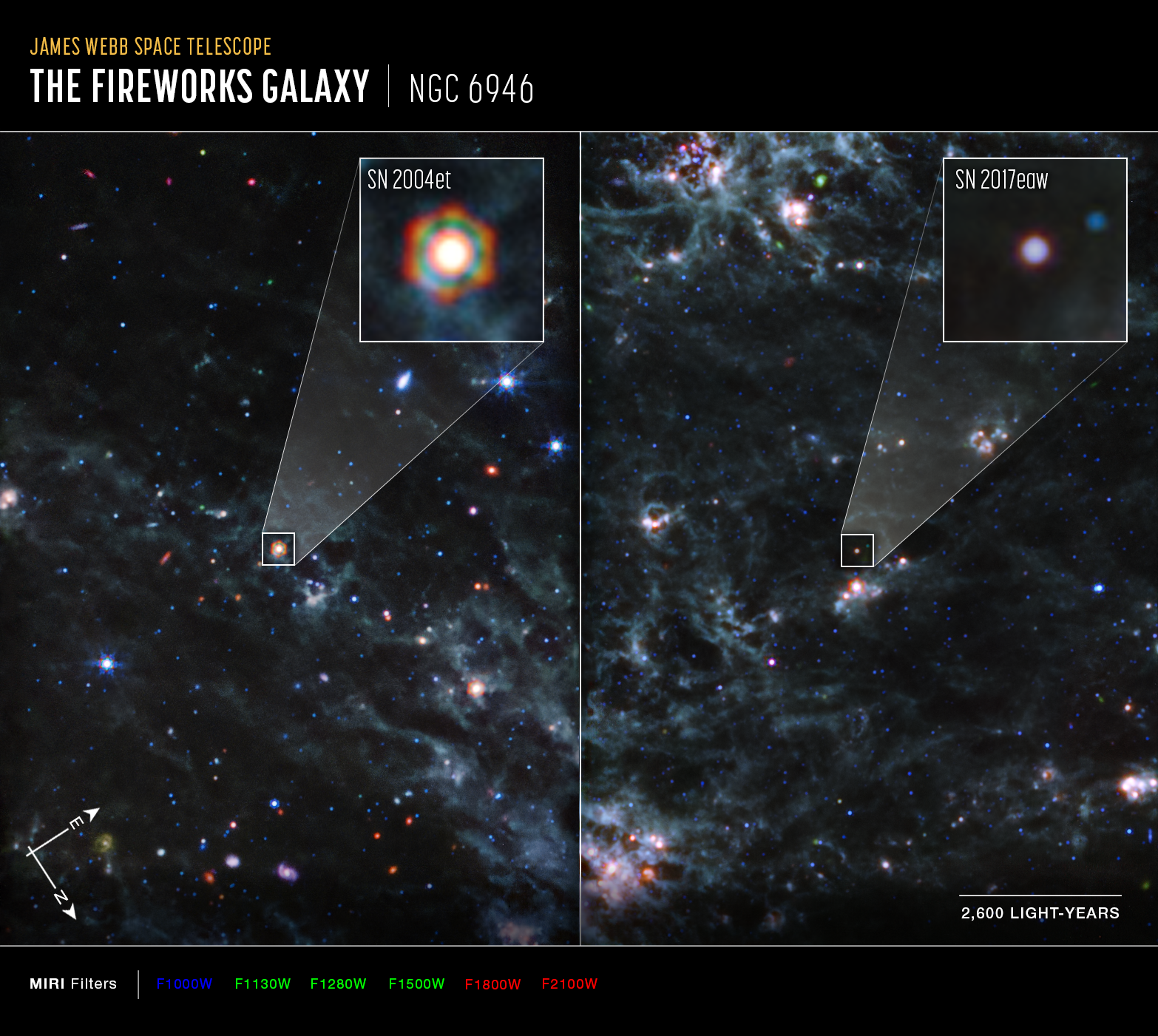

Researchers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have made major strides in confirming the source of dust in early galaxies. Observations of two Type II supernovae, Supernova 2004et (SN 2004et) and Supernova 2017eaw (SN 2017eaw), have revealed large amounts of dust within the ejecta of each of these objects. The mass found by researchers supports the theory that supernovae played a key role in supplying dust to the early universe.

Dust is a building block for many things in our universe – planets in particular. As dust from dying stars spreads through space, it carries essential elements to help give birth to the next generation of stars and their planets. Where that dust comes from has puzzled astronomers for decades. One significant source of cosmic dust could be supernovae – after the dying star explodes, its leftover gas expands and cools to create dust.

“Direct evidence of this phenomenon has been slim up to this point, with our capabilities only allowing us to study the dust population in one relatively nearby supernova to date – Supernova 1987A, 170,000 light-years away from Earth,” said lead author Melissa Shahbandeh of Johns Hopkins University and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. “When the gas cools enough to form dust, that dust is only detectable at mid-infrared wavelengths provided you have enough sensitivity.”

For supernovae more distant than SN 1987A like SN 2004et and SN 2017eaw, both in NGC 6946 about 22 million light-years away, that combination of wavelength coverage and exquisite sensitivity can only be obtained with Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument).

The Webb observations are the first breakthrough in the study of dust production from supernovae since the detection of newly formed dust in SN 1987A with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope nearly a decade ago.

Another particularly intriguing result of their study isn’t just the detection of dust, but the amount of dust detected at this early stage in the supernova’s life. In SN 2004et, the researchers found more than 5,000 Earth masses of dust.

“When you look at the calculation of how much dust we’re seeing in SN 2004et especially, it rivals the measurements in SN 1987A, and it’s only a fraction of the age,” added program lead Ori Fox of the Space Telescope Science Institute. “It’s the highest dust mass detected in supernovae since SN 1987A.”

Observations have shown astronomers that young, distant galaxies are full of dust, but these galaxies are not old enough for intermediate mass stars, like the Sun, to have supplied the dust as they age. More massive, short-lived stars could have died soon enough and in large enough numbers to create that much dust.

While astronomers have confirmed that supernovae produce dust, the question has lingered about how much of that dust can survive the internal shocks reverberating in the aftermath of the explosion. Seeing this amount of dust at this stage in the lifetimes of SN 2004et and SN 2017eaw suggests that dust can survive the shockwave – evidence that supernovae really are important dust factories after all.

Researchers also note that the current estimations of the mass may be the tip of the iceberg. While Webb has allowed researchers to measure dust cooler than ever before, there may be undetected, colder dust radiating even farther into the electromagnetic spectrum that remains obscured by the outermost layers of dust.

The researchers emphasized that the new findings are also just a hint at newfound research capabilities into supernovae and their dust production using Webb, and what that can tell us about the stars from which they came.

“There’s a growing excitement to understand what this dust also implies about the core of the star that exploded,” Fox said. “After looking at these particular findings, I think our fellow researchers are going to be thinking of innovative ways to work with these dusty supernovae in the future.”

SN 2004et and SN2017eaw are the first of five targets included in this program. The observations were completed as part of Webb General Observer program 2666. The paper was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on July 5.

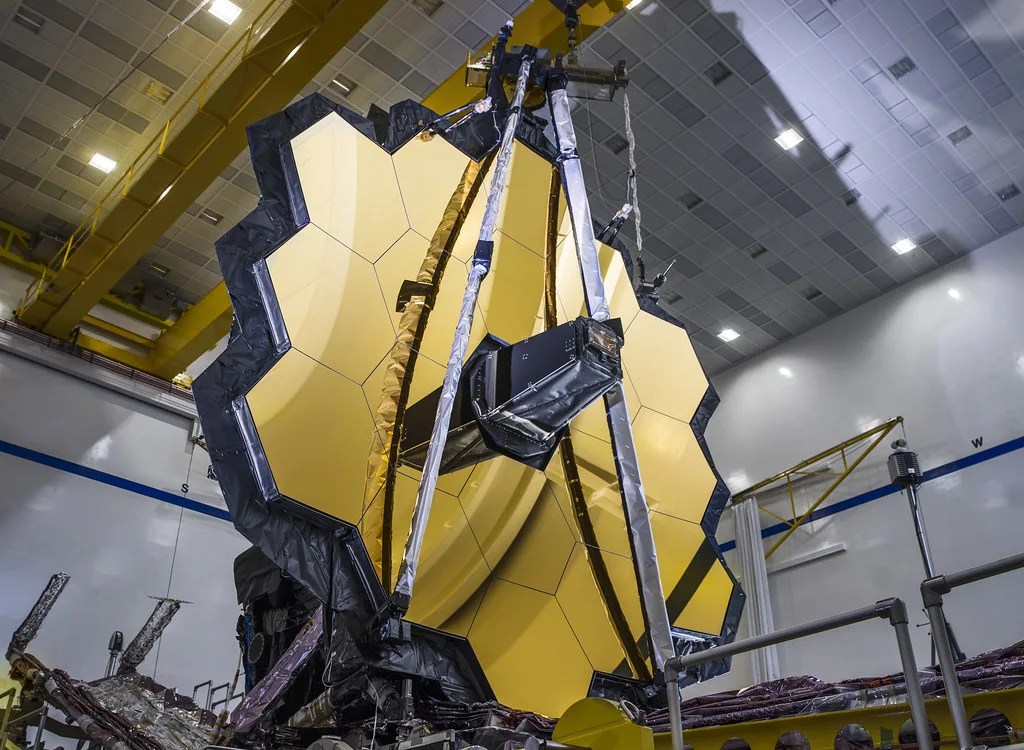

The James Webb Space Telescope is the world’s premier space science observatory. Webb will solve mysteries in our solar system, look beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probe the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency), and CSA (Canadian Space Agency).