The Sun’s Smallest Companions

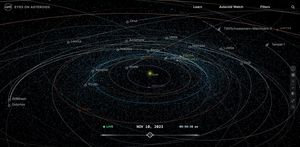

There's a lot orbiting the Sun. Aside from the eight planets, there are billions of smaller objects, too. One type is the asteroids, hunks of rock left over from the formation of the solar system. They mostly orbit in two belts: one between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, and one out beyond Neptune. Comets are icy bodies which swing through the solar system on long, highly elliptical orbits. Most of them orbit far beyond Pluto, in the Oort Cloud.

When comets swing in close to the Sun, it heats up their outer shell. When the solar wind pushes against the ionized gases this releases, it causes them to trail away from the Sun in a long, straight, and thin ion or plasma tail. Meanwhile, the comet's dust tail is made up of loose, gritty material released by the melting of its surface layers. This forms a hazy, smoke-like dust tail that trails after the comet along the path of its orbit.

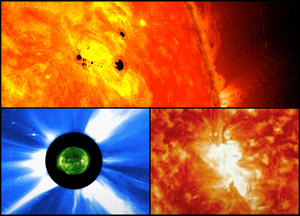

These tails are one of the most dynamic images that we associate with comets, as they can bloom up to many times larger than the size of planets as observed from Earth. When the comet departs the inner solar system, the tail fades as the comet freezes up again. But aside from being amazing to view, comet tails are also an important part of the way we study the Sun, including its magnetic field and the effects of the solar wind.

Messengers from Afar

Most comets, including the famous Halley’s Comet, come from within our solar system. That is to say that they were born in the same protoplanetary disk that birthed the Sun and the other bodies around it. We know this mostly by studying their orbits, since the paths they carve through space could only occur if they began on a closed orbit around the Sun.

But these visitors can come from farther away, too. Much farther. On October 19, 2017, the University of Hawaii’s Pan-STARRS1 telescope, which is funded by NASA’s Near-Earth Object Observations (NEOO) Program, tracked a possible asteroid in Earth’s neighborhood. Continued observations showed that it was travelling at over 196,000 miles per hour (87.3 kilometers per second) and was accelerating into the inner solar system. That’s comet behavior.

Initially dubbed 1I/2017 U1, the object was given the name ‘Oumuamua by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). This means “a messenger arriving from afar and arriving first” in Hawaiian, and recognizes that it is the first interstellar object known to have visited our solar system. It went beyond Saturn’s orbit in early 2019 and is now heading back into deep space.

The New Kid on the Block

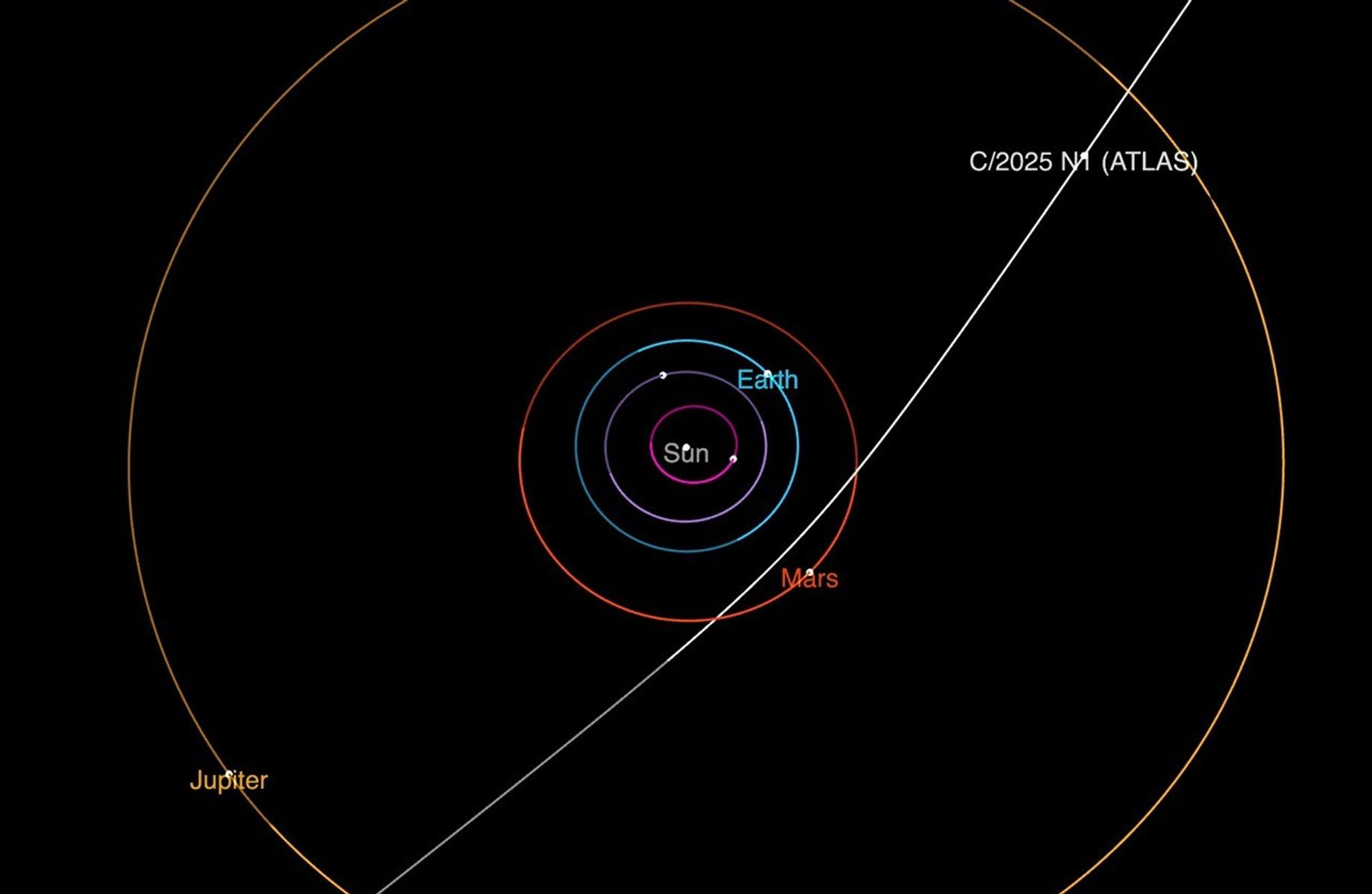

‘Oumuamua was first, but not last. Scientists now estimate that about one such object flies through our solar system every year – and now we know how to look for them. On July 1, 2025, the NASA-funded ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System) survey telescope in Rio Hurtado, Chile, reported a new interstellar visitor. It was given the name 3I/ATLAS.

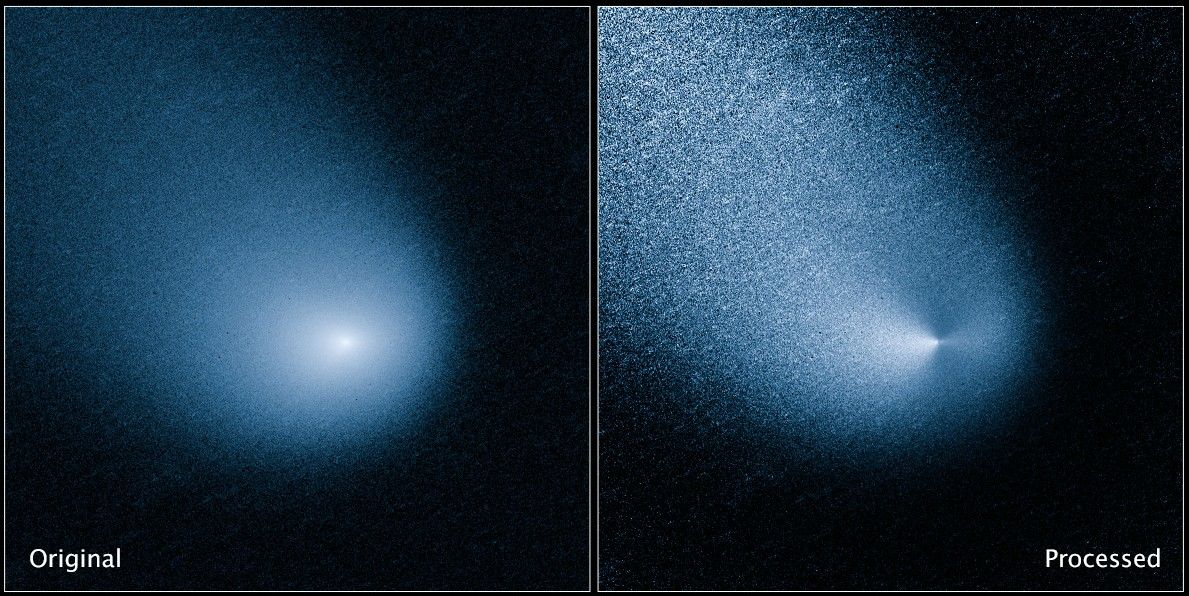

3I/ATLAS has been extensively observed since then. The Hubble Space Telescope observed it on July 21, 2025, when it was about 277 million miles (446 million kilometers) away from Earth. These observations revealed a teardrop-shaped tail flying off of the nucleus, which scientists estimate to be anywhere up to 3.5 miles (5.6 kilometers) in diameter. Other observations have come in from assets as diverse as the James Webb Space Telescope, the Perseverance rover on Mars, and ESA/NASA’s Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO).

How Heliophysics Can Help

The Sun is so bright that its light would burn out many of the telescopes which would otherwise observe 3I/ATLAS as it approaches perihelion, or closest approach to the Sun. But NASA’s heliophysics mission fleet is designed to observe the Sun closely, meaning that these spacecraft can keep an eye on 3I/ATLAS as it nears the Sun. This will allow scientists to gather vital data about how comets interact with the Sun, the solar wind, and more, as well as how interstellar objects like 3I/ATLAS differ from objects native to our own solar system.

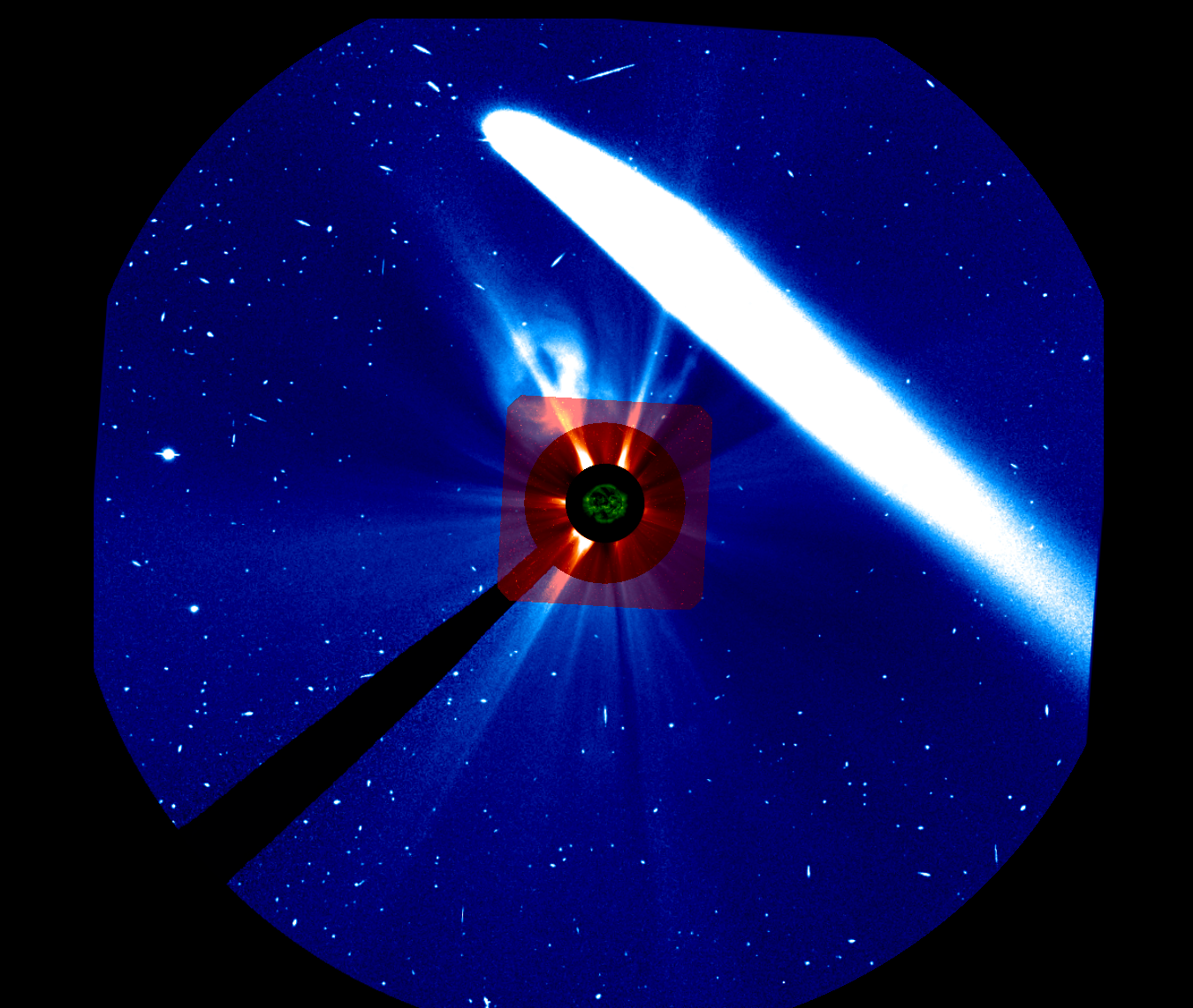

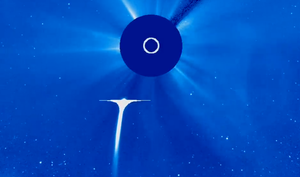

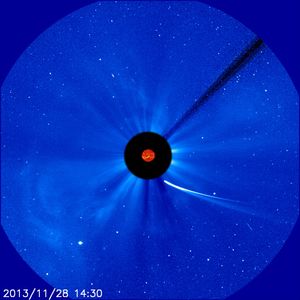

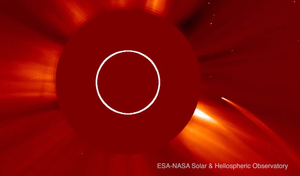

One instrument observing 3I/ATLAS is SOHO’s Large Angle and Spectrometric Coronagraph (LASCO). A coronagraph is a telescope which blocks light from the solar disk in order to see the Sun’s faint atmosphere, or corona. LASCO has three coronagraphs that image the corona from 1.1 to 32 solar radii (one solar radius is about 420,000 miles, or 700,000 kilometers).

LASCO was able to see 3I/ATLAS when it made its closest approach to the Sun on October 30, 2025. At this closest approach, the object was about 1.36 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, or about 126 millions miles (203 million kilometers). It won’t make its closest approach to Earth until sometime around December 19, when it will be about 1.8 AU from our planet. From there, it will proceed back out of the solar system on a long, dark journey through interstellar space.

What We Can Learn Together

While 3I/ATLAS makes its close approach to the Sun, LASCO and other such instruments will help gather as much data as possible. After the images they return are processed, this data should help scientists to better understand where this strange visitor comes from and what it is made of. Using data gathered on objects like 3I/ATLAS, scientists can work backwards to make more educated inferences about the origins of planetary systems, including our own.

Heliophysics can also use data from comets to make discoveries about how the Sun and other stars interact with objects in their orbit. For example, scientists used observations of the tails of comets to help prove the existence of the solar wind. Studying comets has also shown how the Sun’s roughly 11-year sunspot cycle contributes to different levels of radiation output.

Sample return missions are another opportunity for scientists to learn about how the Sun affects the rest of the solar system. In 2006, the Stardust mission returned samples of Comet Wild 2, and in 2023, OSIRIS-Rex brought back samples from asteroid Bennu. Studies of these samples have offered clues about how the early components of present day planetary bodies were affected by solar radiation, how the solar wind has changed over time, and more.

These cooperative interactions go far beyond 3I/ATLAS. Learning about the Sun helps us to better understand other stars, just as our observations of other stars helps us to better understand our Sun. By focusing on areas where disciplines like heliophysics, planetary science, and astrophysics intersect and overlap, we gain even more insight on our place in the universe.