From the first detection of active volcanoes outside Earth to the first up-close images of Neptune, the 40-year Odyssey of NASA's Voyager mission is full of unforgettable memories. Voyager 1, the farthest human-made object, launched on Sept. 5, 1977, and Voyager 2, the second farthest, launched on Aug. 20, 1977. In honor of their 40th launch anniversaries, we asked scientists and engineers who have worked with the spacecraft, as well as enthusiasts inspired by the mission, to share their most meaningful Voyager moments.

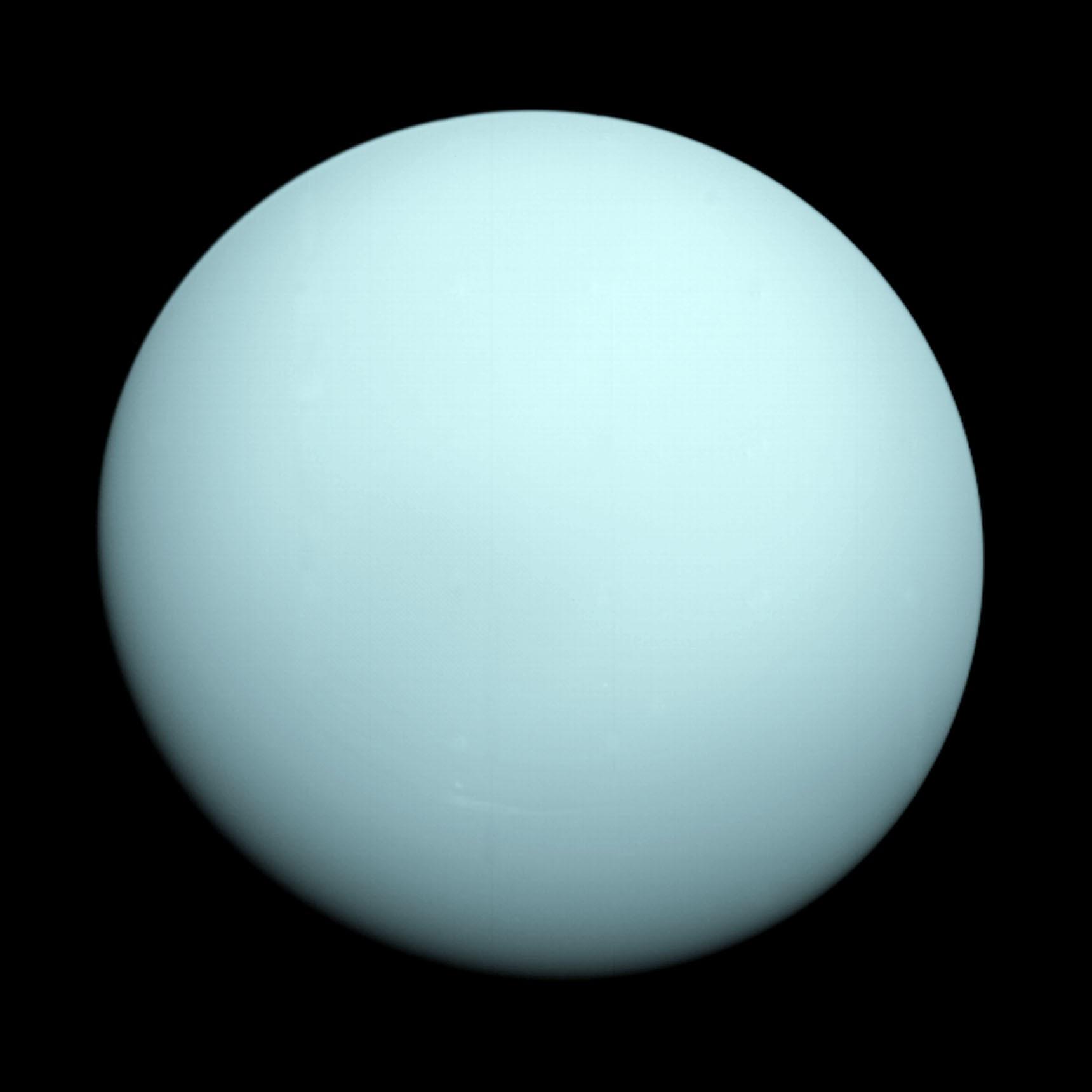

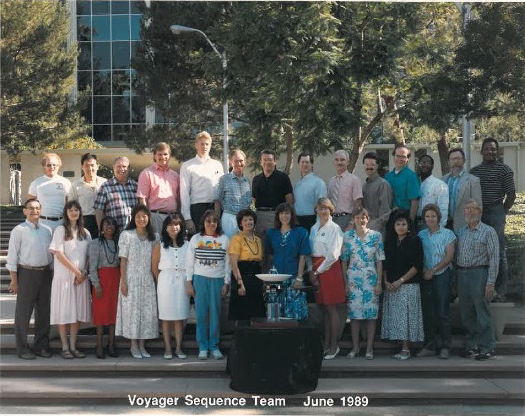

Some Voyager team members began their careers in the early days of the mission. Designing science sequences for the 1986 Uranus encounter was a first job after college for Suzanne Dodd, now the Voyager project manager: "We were making history," she said.

Jamie Rankin, who started working with Voyager Project Scientist Ed Stone just days after Voyager 1 entered interstellar space in 2012: "Every day as a graduate student here is like living in a legacy of discovery," she wrote.

We were making it happen. We were making history.

Suzanne "Suzy" Dodd

Voyager Project Manager

What is your most meaningful Voyager moment and why?

-

"I loved adventure stories as a child, turned to science fiction as a young adult, studied math and physics at Georgia Tech, often gazed at the night sky and dreamed of one day exploring the planets. After learning the tricks of the trade at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, I was thrilled in late 1974 to receive a call from Bud Schurmeier, project manager of the Mariner Jupiter/Saturn 1977 mission (or simply MJS77), which was later named Voyager. He offered me the job of “mission analysis and engineering manager.” I would be working with the great team of dedicated people Bud had assembled."

-

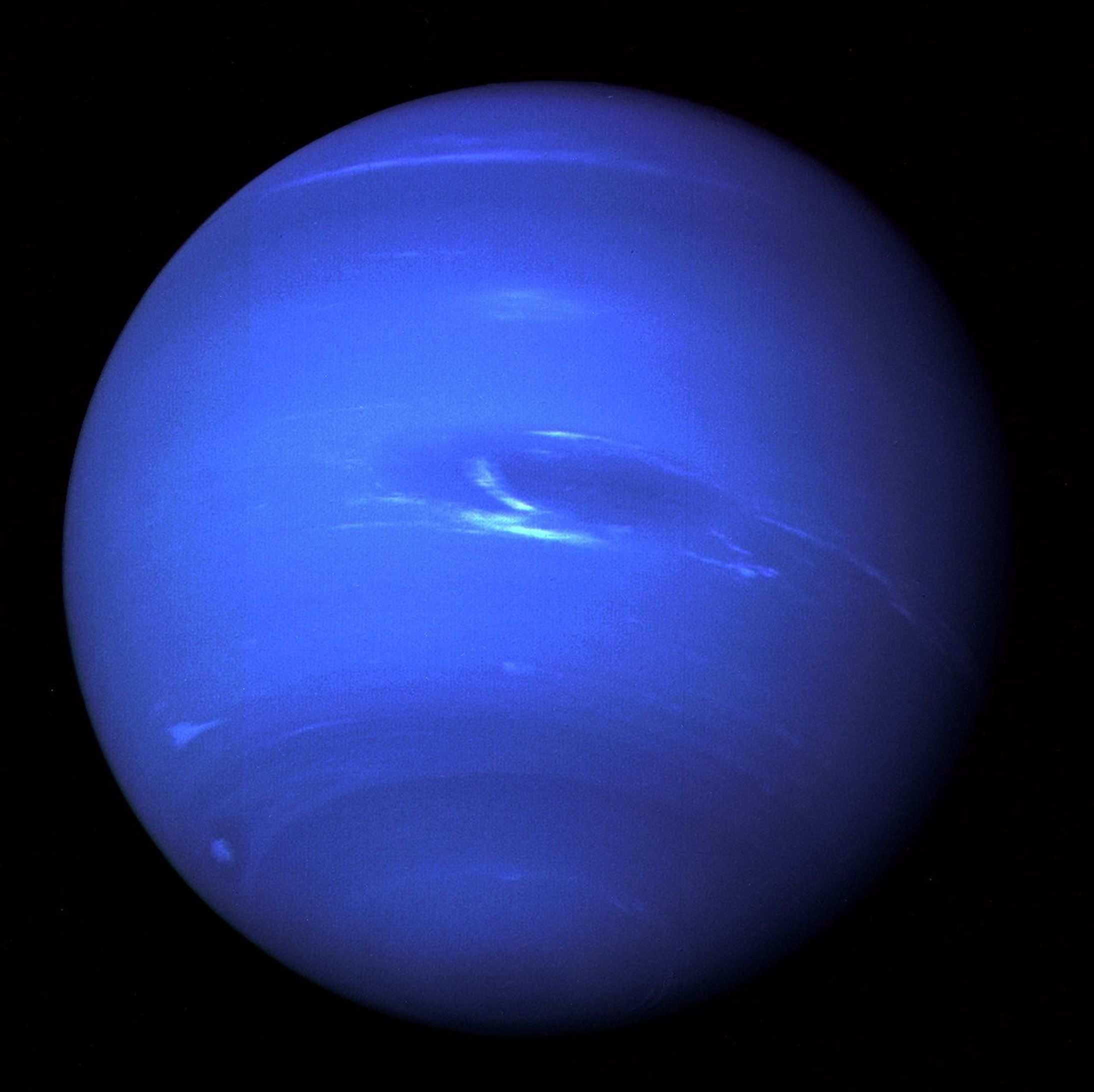

"I was 9 in 1989 when my parents let me stay up to watch the PBS coverage of Voyager 2's flyby of Neptune. I remember my parents debating whether I would even be interested. I think I really wanted to see it because I'd heard about it. I was interested in space, and I wanted to be an astronaut, but only in a vague way."

-

"For me, the highlights of Voyager were clearly the planetary encounters. All six of them were wonderful experiences where every day we saw and learned new things. We had a lifetime of discovery packed into each one."

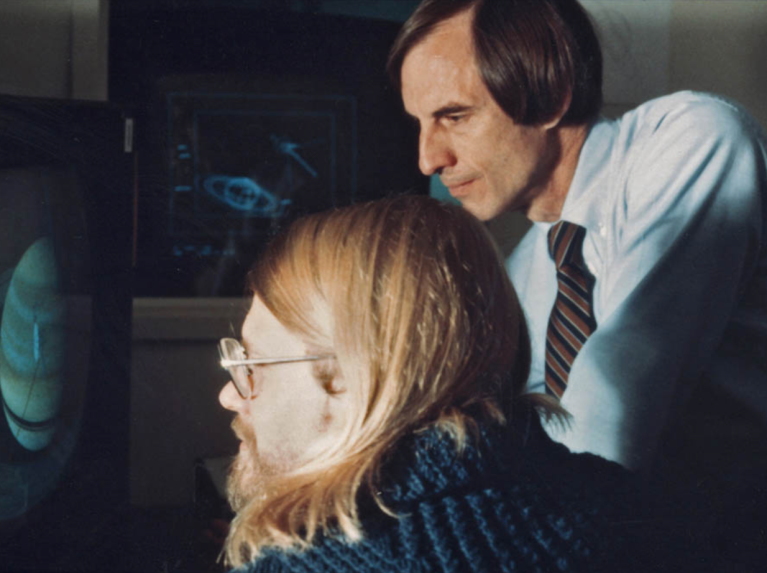

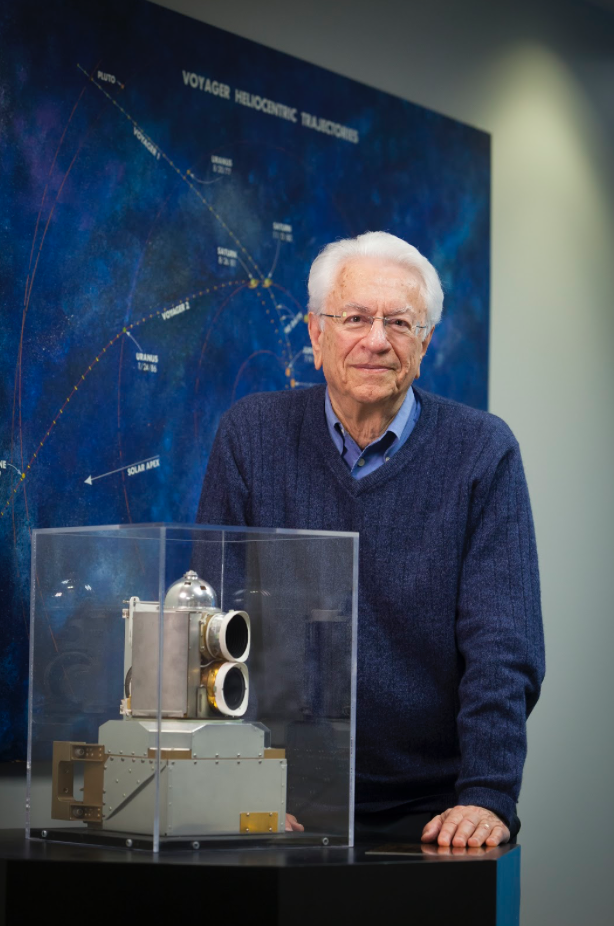

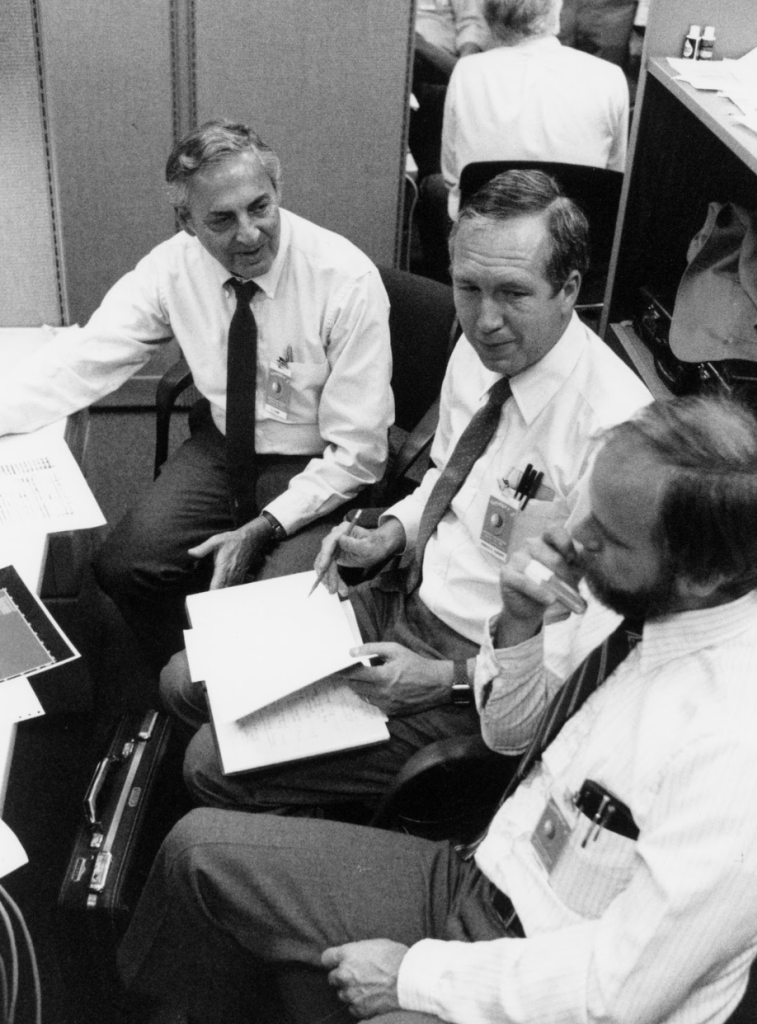

Ed Stone, Voyager Project Scientist

Ed Stone, Voyager Project Scientist

"My involvement with the Voyager mission started in 2001, when I started using and adapting a major computational code developed by the University of Michigan to study the outer layer of the heliosphere, where this bubble of plasma that the Sun blows around itself touches interstellar space."

"I arrived in Pasadena, California, to begin graduate school at Caltech on Friday, August 31, 2012 -- just six days after Voyager 1’s own interstellar arrival. My new advisor, Ed Stone, invited me to attend the Voyager Science Steering Group meeting which started the following Monday."

"I think back to the days we launched Voyager 40 years ago, and it seemed like one more shot into the unknown -- albeit rather ambitious. We just wanted to get to Jupiter and Saturn in the next four years and explore the “uncharted territory.”

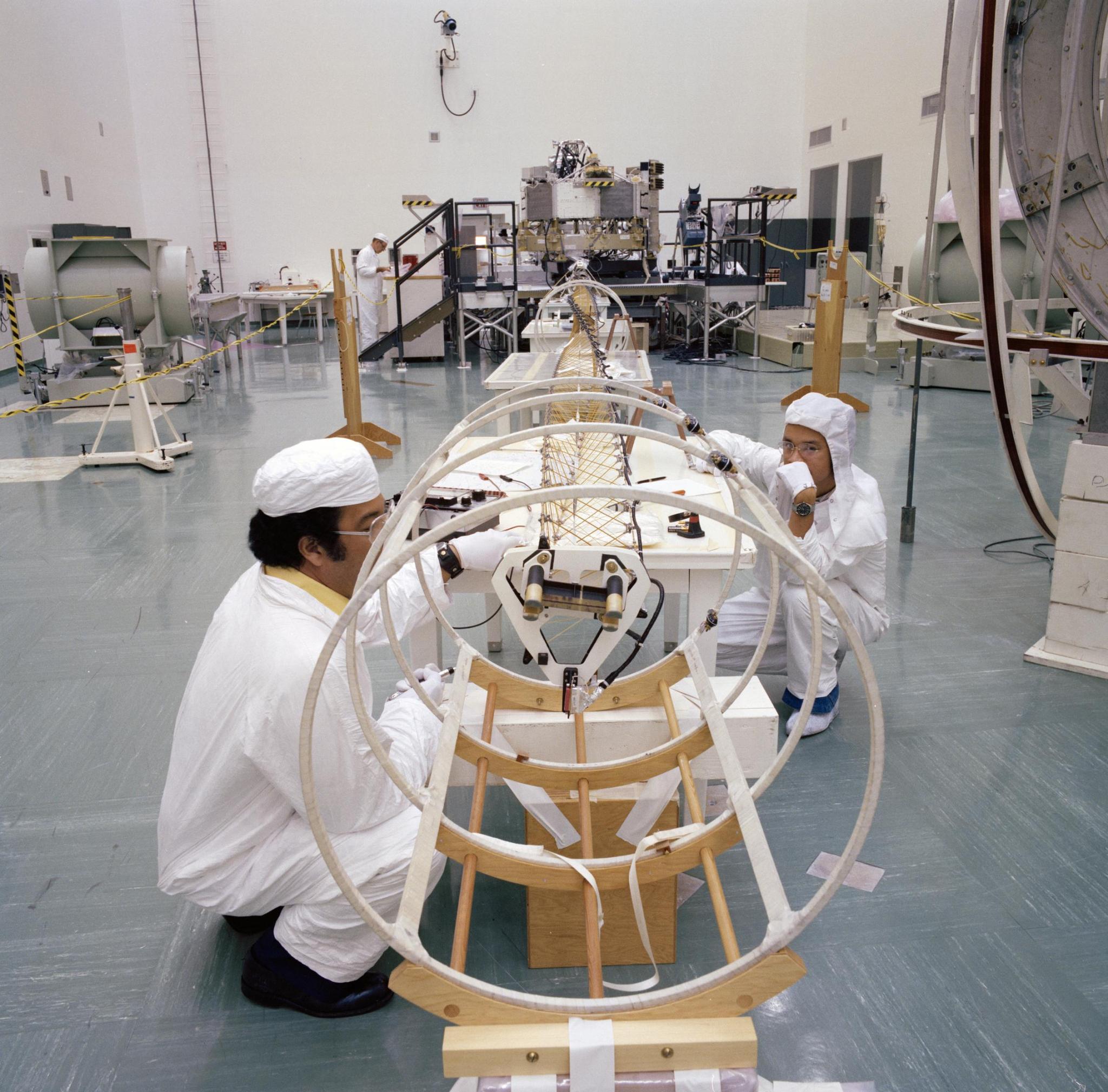

"In late 1972, I was hired into NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to develop the Voyager power subsystem design. My background included engineering on the Phoenix missile and F-15 radar transmitter at Hughes Aircraft. The opportunity to work at a world-class laboratory like JPL was the pinnacle of my career aspirations."

"The five days of January 24 to 28, 1986 -- starting when Voyager 2 flew by Uranus (“the planet that got knocked on its side”) and ending with the painful tragedy of the Challenger accident -- are forever etched in my memory of unforgettable life experiences."

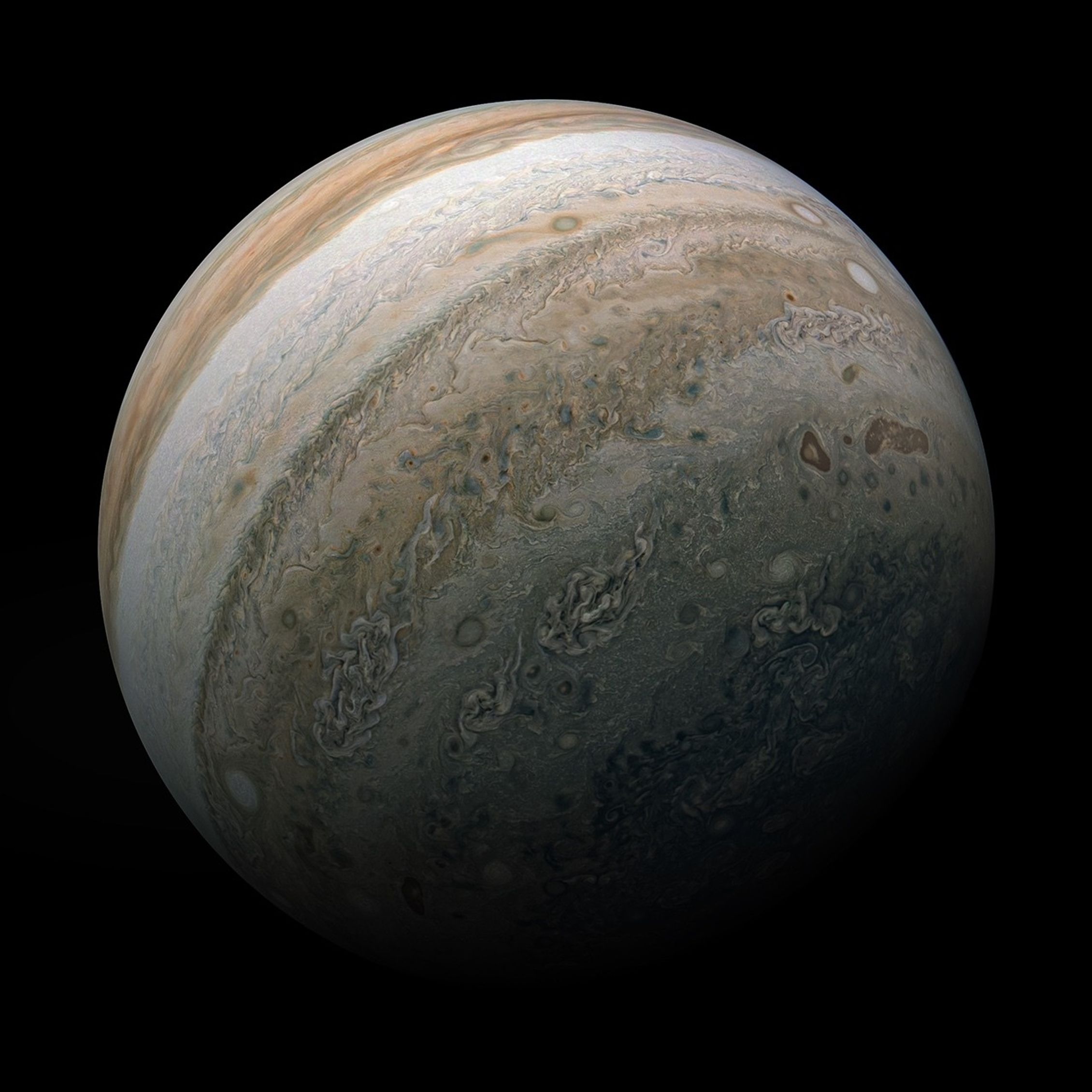

"In 1610, when Galileo (Galilei) was the first person in the world to look through a telescope at an astronomical object, he looked at Jupiter, and he saw four moons going around it. The historical importance of that event is it convinced him that Copernicus was right -- the Sun was the center of the solar system, and the planets were revolving around it."

It wasn't just that it was a technically great mission. The people who I worked with, the generosity and kindness with which they treated me, has stayed with me always.

Steve Squyres

Role on Voyager: Graduate Student

"Voyager was one of the most wonderful, formative, unforgettable experiences of my entire career. I was very, very fortunate that in graduate school I worked with several members of Voyager imaging team."

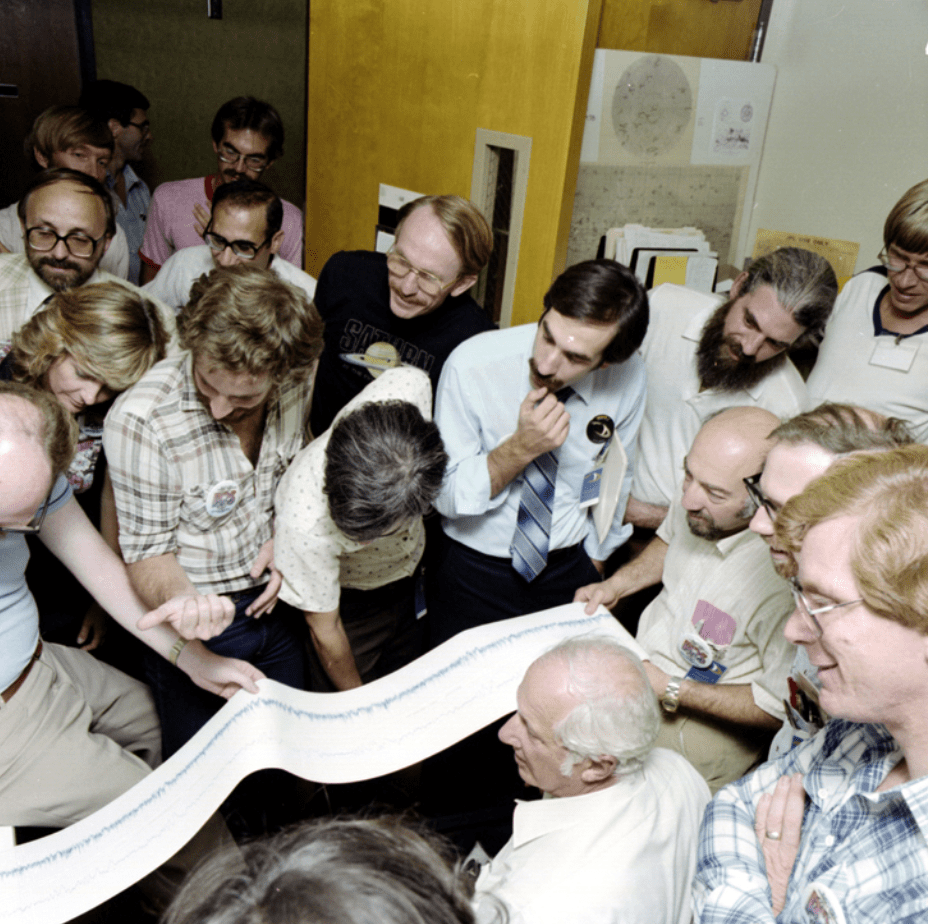

"There was great excitement in the office as the scientists started arriving in the weeks leading up to the flyby. I got to meet Carl Sagan and had him autograph my copy of Cosmos."

"I started working for the Voyager Imaging Team in 1977, shortly before launch, and continued on through the Neptune encounter. There were so many memorable moments, but one of my favorites occurred in the spring of 1990..."

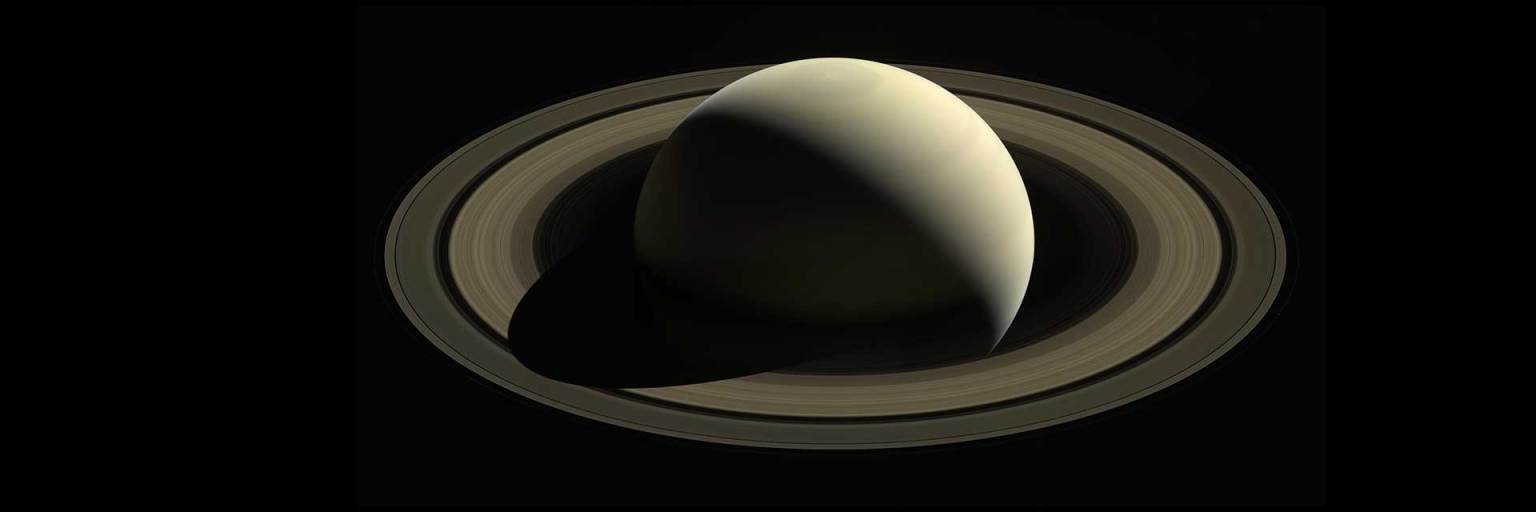

"A single paper plot over a quarter of a mile long showed the attenuation of the starlight by the ring material, at a resolution of greater than 20 meters, for the entire 70 million-meter length of the cut through the rings’ radius. What a spectacular event that unfolded after so much hard work by so many people!"

-

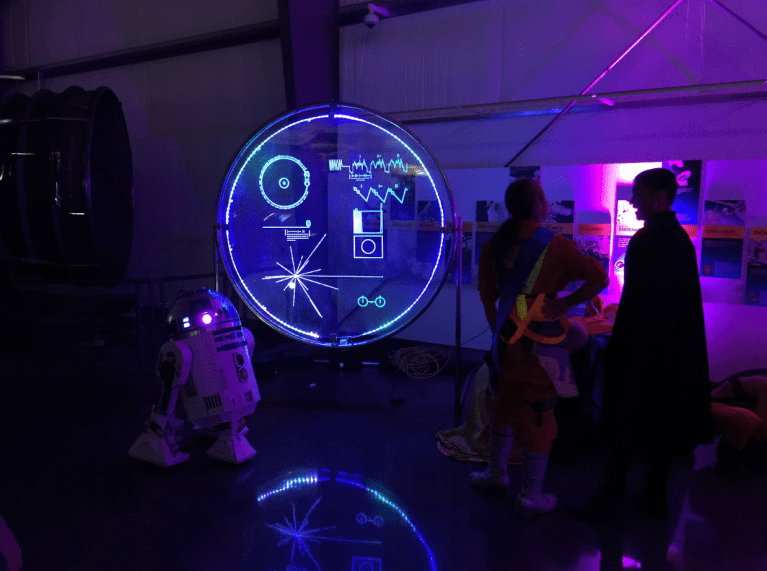

"One of my favorite stories in science history is Voyager’s observation of tidally driven volcanic activity at Jupiter’s tiny moon Io, first theorized just prior to the mission’s arrival at Jupiter. As I grew up I knew I wanted to contribute to answering big questions, including, "Are we alone in the universe?" The Voyager Golden Record, which carries a capsule of sounds and images from Earth in the chance that some day an alien civilization might recover the spacecraft, came to symbolize for me humanity's commitment to pursuing the answers to such questions and the hope that our better nature will see us through to the future."

"Working on a mission like Voyager, with the opportunity to explore the planets, was something I dreamed about since first looking at Jupiter and Saturn in third grade with my tiny telescope. I wondered what these worlds looked like up close and Voyager gave me a chance to find out."

"One of my more memorable moments, after watching Voyager 1 launch from the Cape in September of 1977, was focused on whether Neptune had a magnetosphere... Part of the challenge was that certain conclusions could only be drawn from actually 'being there,' and in mid-August 1989, Voyager was bearing down on its rendezvous with Neptune."

"Back in 1989, I was hired by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to work on the General Science Data Team for the Voyager project’s Neptune flyby. Incredible! My first job at JPL was on what could reasonably be argued as the best mission ever flown by JPL at the peak of its experience and capabilities."

"When I was graduating from college in Texas with a computer science degree, I was all set to go to work for IBM in San Jose (IBM back then for many of us was like Google now); I had never heard of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory or Voyager. However, fate brought me to JPL and to the Voyager project."

"I have had the unspeakably good fortune to have worked on Voyager throughout my entire career and to continue to do so. As a graduate student, I worked on the Plasma Wave Science (PWS) instruments prior to launch. (I placed a 'Uranus or Bust' sticker on the Voyager 2 PWS shipping container – how little I knew about how far it would go!)."

"Finally, for me, a cosmic-ray physicist, one of the highlights by far has been the crossing of the heliopause, the boundary of the Sun’s magnetic bubble, into interstellar space by Voyager 1. The Voyagers will orbit the center of the galaxy forever. It is humbling to think that I’ve been a part of such a fantastic mission."

My daily interactions across the JPL engineering matrix on Voyager-specific issues and problems provided me with a host of friendships and a knowledge base on implementation of a long-lived spacecraft. Who could have predicted that this hardware would still be functional some 40 years after launch?

Robert Detwiler

Power System Cognizant Engineer