Nancy Grace Roman

Astronomer

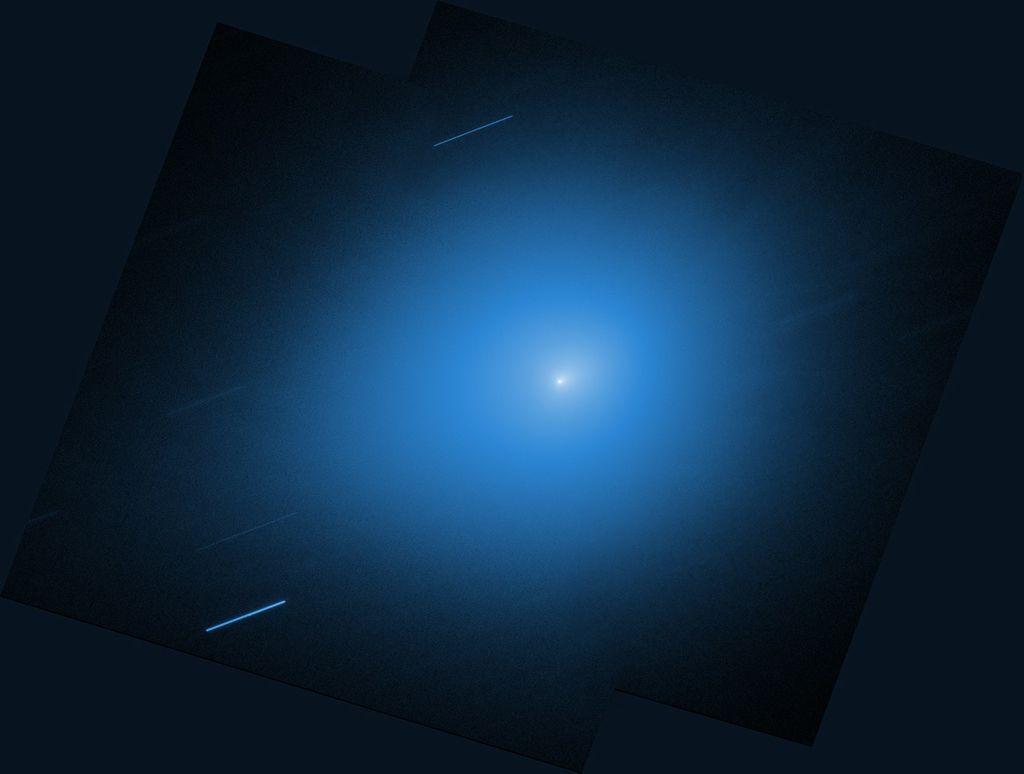

After three decades in orbit and thousands of discoveries, it is hard to believe that the Hubble Space Telescope was ever a contentious idea. However, in the mid-20th century, a budget-starved NASA and a post-World War II government were hesitant to follow the ambitious ideal of a giant new telescope. One woman, nicknamed the “Mother of Hubble,” pushed the first major space-based telescope from hopeful speculation to pioneering reality.

Breaking Barriers

As a woman in science, Nancy Grace Roman was met with skepticism or rejection at nearly every turn. “I was told from the beginning that women could not be scientists,” she often recounted. Her high school counselor scoffed at her desire to take algebra over Latin and a college professor gave her the highest praise she had yet received: that she “might” make it as a woman in physics. Despite opposition, Roman remained steadfast in her desire to pursue astronomy, going on to become NASA’s first female executive.

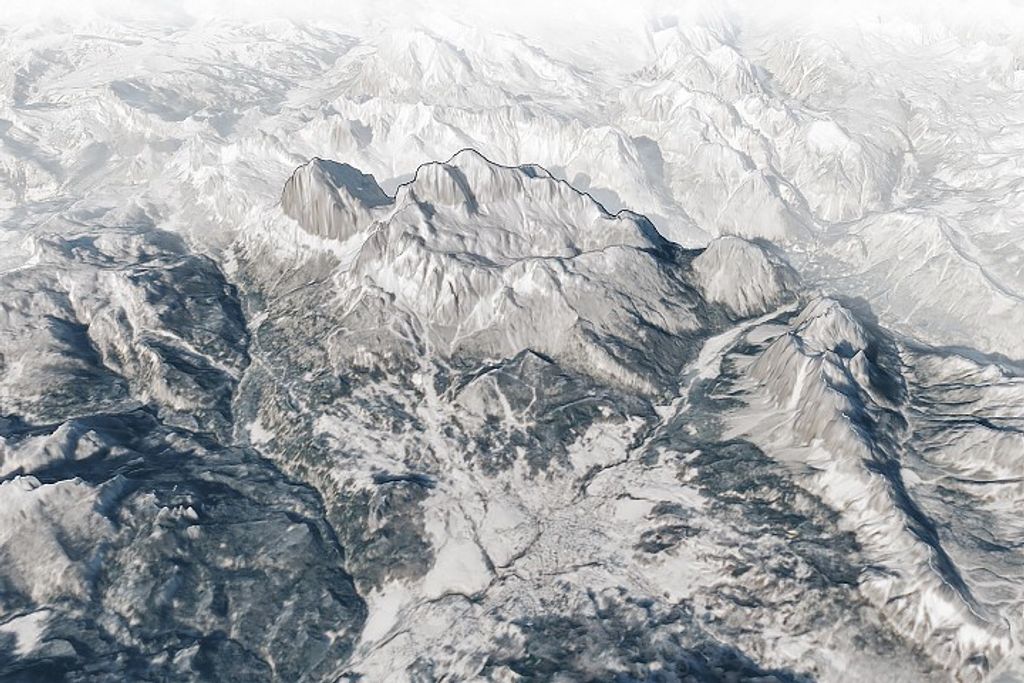

Roman was born on May 16th, 1925 to Irwin Roman, a geophysicist, and Georgia Smith Roman, a music teacher. She spent her childhood moving around the country for her father’s work, living in cities from Nashville to Reno to Baltimore. Her mother took her on nature walks to see birds and trees, but the constellations were what enraptured her most. By 6th grade, Roman had organized her friends into an astronomy club, and by 7th grade she knew that she wanted to devote her life to studying the cosmos.

Roman received her bachelor’s in astronomy from Swarthmore College in 1946 and her doctorate in astronomy from the University of Chicago in 1949. While she loved teaching at the university and researching stars at the university-operated Yerkes Observatory, she noted that there were no women at her institution with tenure in astronomy, despite their many years of experience. In fact, at that time, there was only one tenured female astronomer in the country. Believing that her career aspirations would be stifled in academia, Roman left to take a position in radio astronomy at the Naval Research Laboratory.

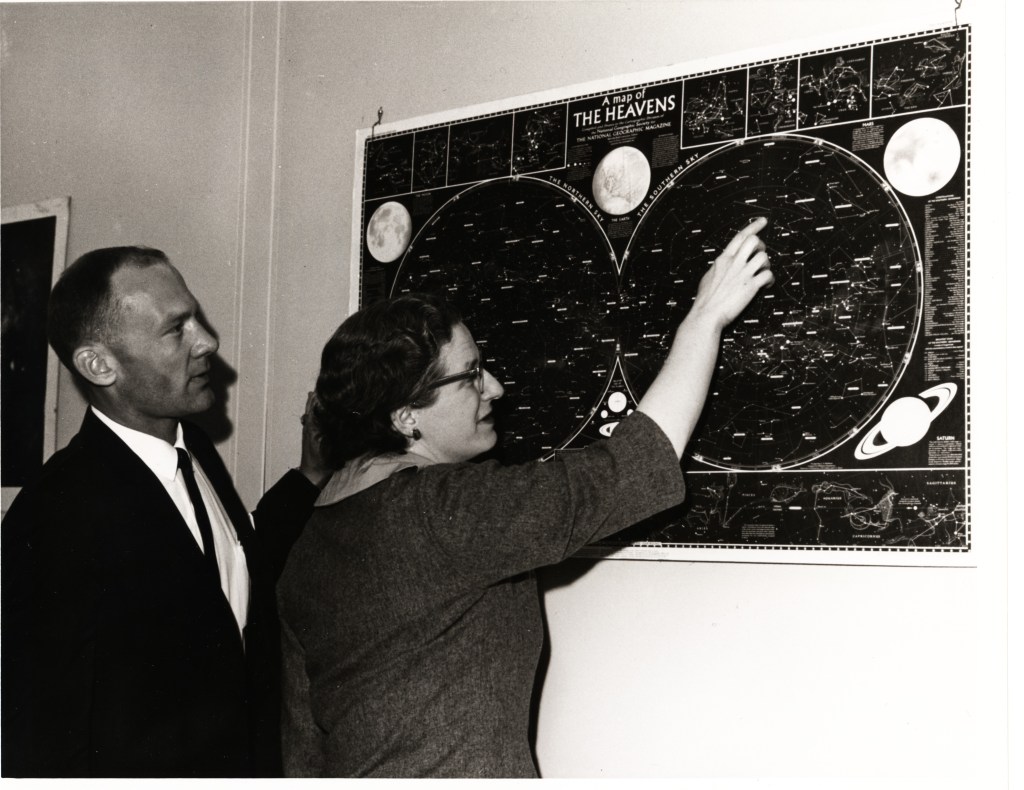

In 1959, an employee at the fledgling NASA asked Roman if she knew someone who might be interested in creating a space-based astronomy program. She volunteered herself and NASA hired her only six months after the agency’s formation. Despite her years of experience and international reputation as a scientist, her previous work had been so underpaid that it was not recognized as employment and she was hired as a new PhD graduate. By 1960, Roman was serving as NASA’s Chief of Astronomy and Relativity, but could still not get past the secretaries without stopping to explain her credentials. Looking back on her career in science, Roman joked, “If I hadn’t been stubborn, I would’ve been talked out of it years earlier.”

Championing Hubble

Roman’s duties at NASA involved securing and administering grant funding for different missions. She liked interacting with scientists in the international community and felt that she could make a big impact by determining which projects moved forward. As Roman listened to the scientists’ goals and aspirations, one thing became clear: there was an intense desire for a space-based telescope.

Over the next two decades, Roman devoted herself to the cause of securing congressional approval and funding for what would become the Hubble Space Telescope. Roman led science and planning committees, brought together scientists and engineers, briefed executive branch officials, and lobbied NASA officials to approve a project as financially and scientifically ambitious as the Large Space Telescope, as it was then called. When talking to Congress, she often quipped that “for the price of one night at the movies each year, each American would receive 15 years of exciting discoveries.” She was almost right – each American has now received over 30 years of discoveries!

From the location where it would be built to the size of its instruments, Roman was involved in every crucial decision about the telescope. Equipped with a strong scientific background and knowledge of the government’s innerworkings, she acted as the link between astronomers and Congress. A born leader, she was known for her unwavering commitment to the mission, regardless of who or what stood in her way. At NASA, Roman felt, people didn’t look at her gender, but at the value of her work.

Nearly 20 years after she started at NASA, Congress approved the mission. One of Roman’s most significant accomplishments to the mission was getting image sensors called charge-coupled devices (CCDs) installed instead of the previous standard sensor. While they seemed to be a risk at the time, CCDs would go on to become the new gold standard for astronomical imaging. Roman also met continuously with scientists to define the scientific objectives for the telescope and how the mission could be designed to meet them, creating a set of minimum specifications for the telescope that she used as a bottom line when speaking to Congress. Roman’s dedication to the Hubble project led her colleague and future Hubble Chief Scientist Ed Weiler to nickname her the “Mother of Hubble.”

Creating a Legacy

Roman retired from NASA in 1979 to care for her mother, but stayed closely involved as a consultant for astronomical catalogs. She returned to work in 1981 in the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Astronomical Data Center, becoming its director in 1995 before retiring again in 1997. She went on to teach science to junior high students at a school in Washington, D.C. and record audio textbooks for the visually impaired.

Throughout her last decades, Roman kept up to date with Hubble’s progress. In 1994, when NASA announced to the public that they were finding solutions for the faulty primary mirror, Roman was in the audience, knitting (as Ed Weiler remarked, “knitting in the back of the room was her trademark”). NASA often invited her back as a speaker, and in 2017 she achieved pop culture fame with her inclusion in the Women of NASA LEGO set. Roman received numerous awards in her lifetime, including the Federal Women’s Award from President John F. Kennedy, the Women in Aerospace Lifetime Achievement Award, and the NASA Exceptional Scientific Achievement Award. Despite her achievements, she would say of Hubble that “I think it would have existed sooner or later without me,” before cheekily adding that “I think the timing was better when I got into it.”

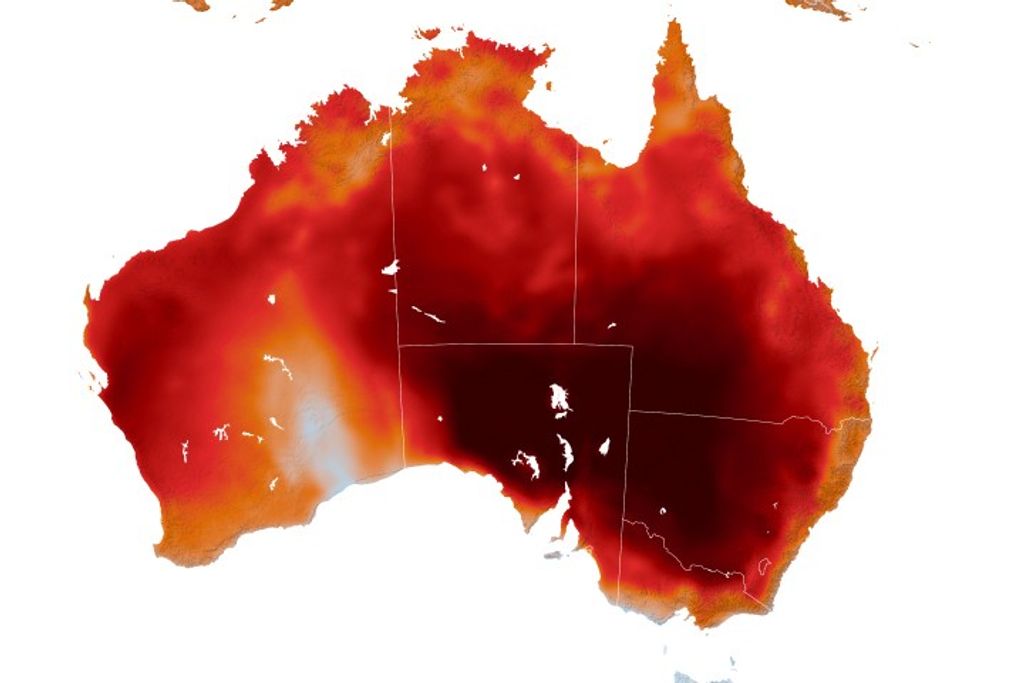

Nancy Grace Roman passed away on December 25th in Germantown, Maryland at the age of 93. In May of 2020 – 15 months after her passing – NASA announced that their next flagship mission would be named in her honor. The Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope is designed to explore questions regarding dark energy, exoplanets, and infrared astrophysics.

Near the end of Roman’s life, she continued to express her desire for gender equality in the sciences, with hopes of seeing more women in senior positions and with higher salaries. When asked how she feels about her accomplishments, she replied: “Hubble has brought astronomy into everyday life in a much more general way than it was before. The fact that it exists is something I’m proud of.”