Astronomers have caught a peek at a rare moment in the final stages of a star's life: a ballooning shroud of gas cast off by a dying star flicking on its stellar light bulb. NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has captured the unveiling of the Stingray nebula (Hen-1357), the youngest known planetary nebula. Twenty years ago, the nebulous gas entombing the dying star wasn't hot enough to glow.

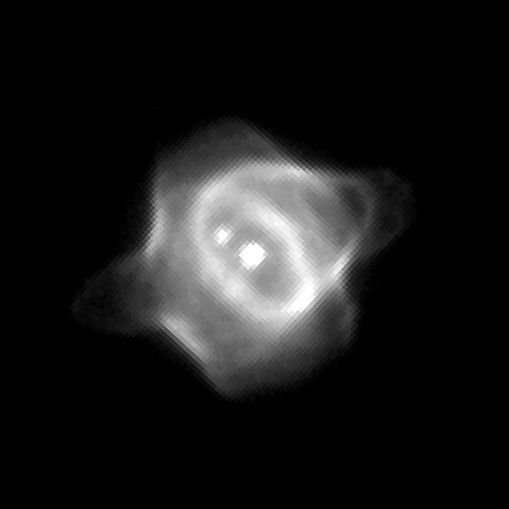

The Stingray nebula (Hen-1357) is so named because its shape resembles a stingray fish. Images of a planetary nebula in its formative years can yield new insights into the last gasps of ordinary stars like our sun.

A planetary nebula forms after an aging, low-mass star swells to become a "red giant" and blows off some of its outer layers of material. As the nebula expands away from the star, the star's remaining core gets hotter and heats the gas until it glows. A fast wind - material propelled outward from the hot central star - compresses the gas and pushes the gas bubble outward.

The central star in the Stingray nebula has heated up quite fast. "Such a fast evolution of the object actually came as a surprise," says Kailash Sahu of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md. "The current theoretical models do not predict such fast evolution for low-mass stars like that of the Stingray nebula."

Adds Matt Bobrowsky of Orbital Sciences Corp. in Greenbelt, Md.: "The Stingray nebula is, in human terms, just an infant because only within the past 20 years did its central star rapidly heat up enough to make the nebula start to glow. It is extraordinary to catch a star in this exceedingly brief phase of its evolution. While stars typically last for billions of years, the transition to a visible planetary nebula takes only about 100 years - the blink of an eye compared to a star's lifetime. It is therefore not surprising that no younger planetary nebula has ever been identified."

The nebula is one-tenth the size of most planetary nebulae and is 18,000 light-years away in the direction of the southern constellation Ara (the Altar). Because of its small size, no details of the Stingray nebula were visible before Hubble observations were carried out.

The creation of twin bubbles of gas, which shape so many planetary nebulae, has always been a mystery to astronomers. The jets of gas revealed in the Hubble images are of great interest to astronomers because many types of astronomical objects - from young stars to active galaxies - produce similar, opposing flows of gas. Many theories have been proposed to explain these jets, but the details of their formation are not yet fully understood. The Hubble images actually reveal how the jets in the Stingray are produced.

"Both theory and observations have indicated that a ring or disk of matter plays a role in forming the opposing outflows," Bobrowsky says. "But these images are significant in showing that, at least in some cases, the situation is somewhat more complex."

The images that Bobrowsky and collaborators acquired show a ring of gas surrounding the central star, with bubbles of gas above and below the ring. The wind emanating from the central star has created enough pressure to blow open holes in the ends of the bubbles, allowing gas to escape. The bubbles act like nozzles that direct the escaping gas into two opposing streams. The images also show bright gas that is heated by a "shock" caused when the central star's wind hits the walls of the bubbles.

A further discovery is a second star within the nebula, indicating that the Stingray's central star is part of a binary star system. This second star is important because astronomers have theorized that a companion might be necessary for the formation of the ring, bubbles, and columns of gas.

There is also evidence that some of the gas in the nebula may be distorted due to the gravity from the companion star - another phenomenon never before seen in a planetary nebula. This appears in the images as a spur of gas forming a bridge to the companion star.

Bobrowsky first observed the Stingray nebula with the Hubble telescope in 1993. Those images were the first to show the structure of the nebula. The new observations were taken in 1997 by Bobrowsky and his collaborators: Sahu of the Space Telescope Science Institute, M. Parthasarathy of the Indian Institute of Astrophysics in Bangalore, India, and Pedro Garcia-Lario of the ISO Science Operations Center in Madrid, Spain. The results are described in the April 2 issue of the journal Nature.