One of the world's largest astronomy archives, containing a treasure trove of information about myriad stars, planets, and galaxies, has been named in honor of the United States Senator from Maryland Barbara Mikulski.

Called MAST, for the Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes, the huge database contains astronomical observations from 16 NASA space astronomy missions, including the Hubble Space Telescope.

"In celebration of Sen. Mikulski's career-long achievements, and particularly this year, becoming the longest-serving woman in U.S. Congressional history, we sought NASA's permission to establish the Senator's permanent legacy to science by naming the optical and ultraviolet data archive housed here at the Institute in her honor," said Matt Mountain, director of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Md.

STScI is the science operations center for Hubble and its upcoming successor, the James Webb Space Telescope.

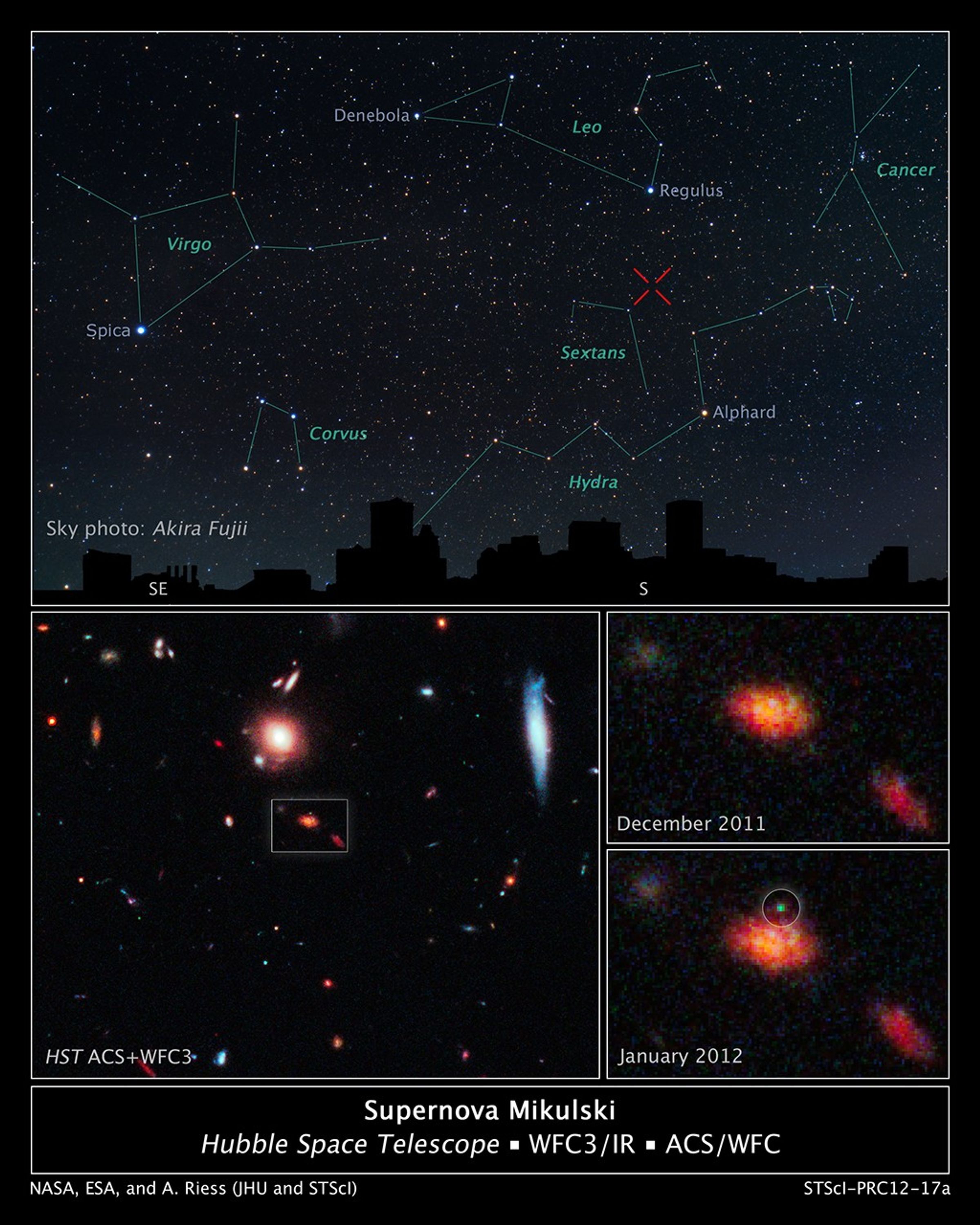

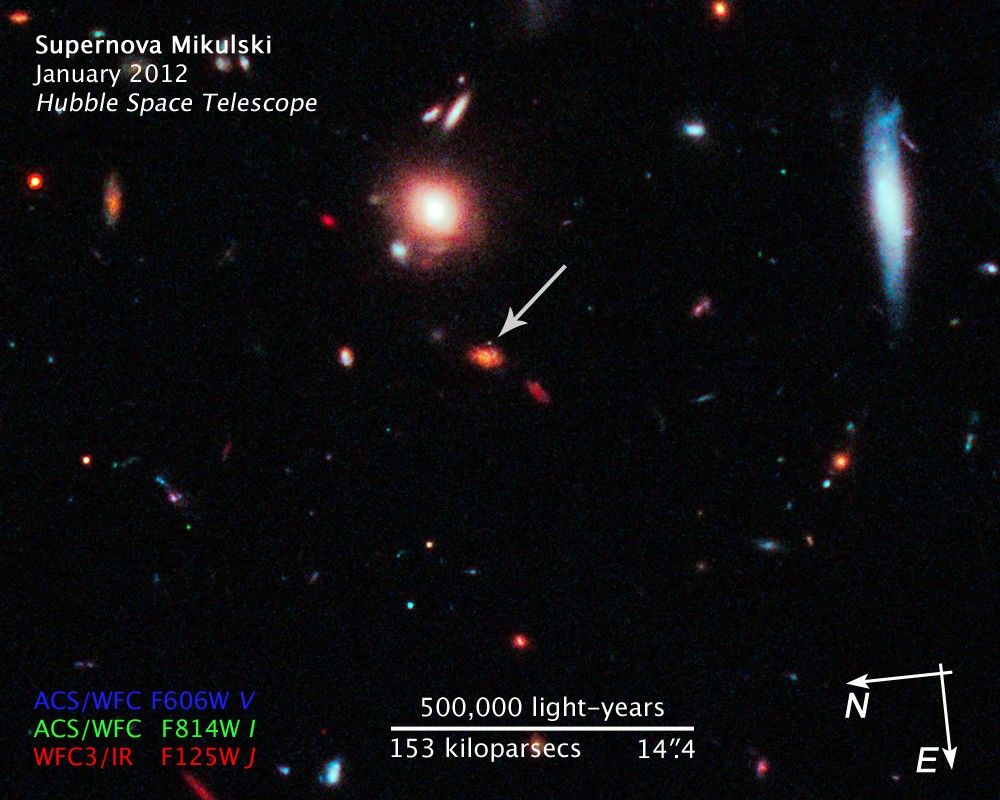

In addition, an exploding star that the Hubble Space Telescope spotted on Jan. 25, 2012, has been named Supernova Mikulski by Nobel Laureate Adam Riess and the supernova search team with which he is currently working. The supernova, which lies 7.4 billion light-years away, is the titanic detonation of a star more than eight times as massive as our Sun.

"I'm humbled and honored to be recognized by our nation's top scientists and innovators as a fighter for science and research," Sen. Mikulski said. "I believe in American exceptionalism; not just because we say we are, but because of our investment in innovation. Through innovation, America has led the way in scientific breakthroughs and discoveries, which inspire future scientists, inventors, and entrepreneurs. I am proud to be the namesake of the archive at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is the enduring legacy of Hubble, and will allow us to peer even further into the origins of the universe after the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope."

MAST is NASA's repository for all of its optical and ultraviolet-light observations, some of which date to the early 1970s. The archive contains information from the golden age of astronomy, spanning the past three decades. An armada of space telescopes has surveyed the universe across a broad spectrum of energies. Data from such groundbreaking missions as the planet-hunting Kepler Observatory and the Galaxy Evolution Explorer are part of the MAST archive.

MAST presently contains approximately 200 terabytes of data, which is nearly the size of the content in the U.S. Library of Congress.

The observational data in MAST are used and reused many times by astronomers. New data are constantly flowing into the archive, but even more data is flowing out. Today, more than half of the published scientific papers containing Hubble data uses archival observations. This number has increased steadily over the past five years.

Now that Hubble has amassed nearly 22 years of data, astronomers are searching the archive to help them address new research areas that were never envisioned by the original observers. MAST archival data have been used to help discover extrasolar planets and distant supernovae.

"As one of the most widely used astronomical resources in the world, significantly more data is extracted from MAST by researchers than the volume of newly ingested data," said Mountain. "What's more, amateur astronomers and educators are becoming more heavily involved in astronomical research than ever because of the 'democratization' of space via a huge publicly accessible astronomical database like MAST. The consequences are that we are on the cusp of a knowledge explosion in astronomy where discoveries are expanding at an unprecedented rate."

Due to its distance, Supernova Mikulski was too faint to have been monitored by ground-based telescopes and required Hubble's unique resolution and sensitivity. Supernovae are natural "time capsules," providing astronomers with a record of past conditions in the universe. Hubble has now undertaken a three-year project to observe the most distant of these stellar explosions. Supernovae are important to understanding the origin of mysterious dark energy, which now dominates the universe, and this work was last year recognized by the award of the Nobel Prize in Physics to two supernova search teams, led by Saul Perlmutter, Brian Schmidt, and Adam Riess.

"We are in a remarkable period for modern astrophysics research," remarked Dr. William Smith, president of AURA, "and it is fitting that Senator Mikulski's persistent championship on behalf of science be permanently recognized by today's events."

The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Md., is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., (AURA) in Washington, D.C. STScI conducts science operations for the Hubble Space Telescope and is the science and mission operations center for the James Webb Space Telescope.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: THE BARBARA A MIKULSKI ARCHIVE FOR SPACE TELESCOPES

Three planets orbiting a nearby, young, massive star were hidden even from the prying eyes of the Hubble Space Telescope when observations were made in 1998.

More than 10 years later, astronomers from two different teams sifting through Hubble's rich data archive found the observations and used a new technique to unearth the three planets orbiting the star, named HR 8799. The Hubble snapshots helped the astronomers confirm the existence of the planets, which initially had been uncloaked by ground-based telescopes.

The research underscores the importance of a bountiful archive. Hubble's vast collection of more than 20 years of observations resides in the Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST), at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Md. The archive also holds data from 15 other NASA telescopes, including current missions such as the Kepler Observatory, a space-based observatory hunting for planets around other stars. In addition, information collected from testing the James Webb Space Telescope, an infrared telescope scheduled to launch later this decade, is housed in the archive. Data from retired missions such as the International Ultraviolet Explorer, an ultraviolet-light satellite that ended its 18-year run in 1996, reside in MAST, too.

The archive is NASA's repository for all of its optical and ultraviolet-light observations, some of which date to the early 1970s. The archive contains about 200 terabytes of data, which is nearly equal to the entire content in the U.S. Library of Congress.

One statistic that proves the archive's popularity and influence is the number of science papers published in the past couple of years that includes MAST data. About 70 science papers in 2010 cited observations taken by the long-retired International Ultraviolet Explorer. And more than half of the nearly 800 published papers in 2011 containing Hubble data used archival observations, a number that has increased steadily almost every year since 2003.

One reason for the surge in the use of Hubble archival data, explains Rick White, MAST's chief archive scientist, is the telescope's longevity. Hubble has amassed almost 22 years of data, and astronomers are finding new uses for the data to explore scientific projects that were not even imagined when the observations were originally carried out.

"Archival science, especially for Hubble data, does not just involve astronomers coming in and cleaning up little dusty corners on the image and doing little bits of science that the astronomer who originally made the image didn't think to do," White explained. "People are doing new science, and it's just as important and just as high-impact as the original work. If you look at all the science that gets generated at the Space Telescope Science Institute, the majority of it is from the archive. And that's only going to increase over the years. It's very clear that by the time the Hubble mission is over, the archive will continue to live on. In fact, the archive is a really cost-efficient way to increase the science."

Started in 1990 as a database for Hubble observations, MAST's main goal is to preserve and protect the information in its vast library and make it easily accessible to users.

MAST staff has constantly been retooling the archive website by adding new technology upgrades so that users, mostly astronomers, can browse and retrieve data more easily. After adding a new operating system in June 2011, the average retrieval time for data decreased from nearly an hour to less than 5 minutes.

Originally, the archive was too large to store on magnetic disks, so the data resided on "jukeboxes," units similar to CD players. Advances in computing technology made it possible to store the entire archive on disks for instant access. Copies of the data are also written to removable optical disks that are stored in an off-site location, in case of catastrophic data loss.

"One of our focuses is developing tools to make it easier for people to browse the data," White said. "Astronomers can't use the archive interfaces to do their science analysis. But they can do a lot of analysis by just previewing the data and looking at it closely to see whether it's going to be suitable for their science."

For Hubble data, the institute has developed the Hubble Legacy Archive (HLA), a separate website linked from the MAST archive that offers enhanced Hubble products and advanced browsing capabilities, such as an interactive display.

Astronomers can enter a list of objects they're interested in and immediately will see small preview images showing the positions of those objects contained in Hubble images, if they were observed by the telescope. They then can display an image in their browser and zoom in and out of the picture. They also can change the contrast level and see the full Hubble field.

"By offering these features, astronomers can analyze an image to see if it fits their research," White explained. "Our goal is to allow people to do as much as possible to determine if the image suits their needs before they get the data, rather than deciding after they download a 500-megabyte image that it's not what they want."

Ironically, because of the HLA's interactive features, astronomers are not downloading data from that archive as often as expected. "They only get the data they absolutely need," said Karen Levay, chief of the Archive Sciences Branch. "Originally, they had to download all the data to look at it. Or, if an astronomer is looking at a really big image and is only interested in a small section, he can just download that section instead of the whole thing. People can be much more efficient about how they select their data."

Now, the archive team is working to add some of the HLA's popular interactive features to the MAST website. That work also will include a new portal integrating data from all of the MAST missions, making them more uniform so that it's easier for users to search for them.

Another new feature the MAST team is working on is tagging press releases and images with their exact positions in the sky and linking them to the original data in the archive. Data in the archive also will offer a link to the press releases and images.

"A link from the press release to the data in the archive gives the public, who are likely to start with press-release-type material, a way to actually get an entry into the archive," White said. "The trick is figuring out how to give the public the right hook to the archive and how to make it understandable and easy to use. So, we're developing some tutorials to help the public navigate MAST."

Today's MAST archive is vastly different from the early days.

"When the Hubble archive was founded in 1990, there was no World Wide Web," White explained. "You think about the things that have changed. If you look at the cost of disk storage, it's dropped a factor of 10,000 since Hubble was launched. Right now, you can buy a terabyte disk for about $80. And in 1990, a terabyte disk, which is not enough to hold a year's worth of Hubble data, would have cost 10,000 times as much, or about $800,000. The technology of the archive has changed tremendously over the life of Hubble."

In the early 1990s, astronomers looking for archival data were mailed a print of the image and a tape of the data. Usually, it would take a week or two to receive the data.

"Things are so easy now," White said. "Astronomers click on a link to request data, and the data gets downloaded to your computer."

Astronomers are reaping the benefits of the MAST team's dedication to constantly improving the archive. Institute astronomer Remi Soummer led one of the teams that used Hubble archival data to confirm the existence of planets around the nearby star HR 8799. His team studied images from Hubble's Near Infrared Camera and Multi-object Spectrometer to confirm two of the planets.

The added time span from the Hubble archival data helped enormously. "This research was not possible without archival data," Soummer said. "The idea was to look at the decade-old images of the HR 8799 system, and measure the motion of these planets. This would not be possible without waiting another 10 years. So, basically, we got 10 years of science immediately by going back in time with the archive."

Now, Soummer is sifting through the Hubble archive in search of more hidden planets circling about 500 stars.