Science

Hubble's Nebulae

These ethereal veils of gas and dust tell the story of star birth and death.

Overview

The space between stars is dotted with twisting towers studded with stars, unblinking eyes, ethereal ribbons, and floating bubbles. These fantastical shapes, some of the universe’s most visually stunning constructions, are nebulae, clouds of gas and dust that can be the birthplace of stars, the scene of their demise – and sometimes both.

Nebulae are made up of gas – primarily hydrogen and helium – and fine cosmic dust. These clouds are part of the interstellar medium of extremely low-density gas and dust that exists between stars in the void of space, material so dispersed through the vastness of the cosmos that it can have a density as low as 0.1 atoms per cubic centimeter. In contrast, a cubic centimeter of the air we breathe on Earth would contain about 10 million trillion molecules.

Nebulae happen in places where the interstellar medium has become dense enough to form clouds. That could be because gravity has pulled the gas and dust together, or because stars have died and spewed their contents into the cosmos. Several types of nebulae exist, and each individual nebula is a unique showcase of the phenomena and processes happening within. They often live side by side, with smaller nebulae populating larger clouds of gas and dust to form giant complexes of star birth and death.

Emission Nebulae

Emission nebulae are so named because they emit their own light. This type of nebula forms when the intense radiation of stars within or near the nebula energizes the gas. A star's ultraviolet radiation floods the gas with so much energy that it strips electrons from the nebula's hydrogen atoms, a process called ionization. As the energized electrons revert from their higher-energy state to a lower-energy state by recombining with atoms, they emit energy in the form of light, causing the nebula's gas to glow.

A famous example of an emission nebula is the Orion Nebula, a huge, star-forming nebula in the constellation Orion. The Orion Nebula is home to a star cluster defined by four massive stars known as the Trapezium. These stars are only a few hundred thousand years old, about 15-30 times the mass of our Sun, and so hot and bright that they're responsible for illuminating the entire Orion Nebula. But thousands of additional, mostly young stars are embedded in the nebula. The most massive are 50 to 100 times the mass of our Sun.

The radiation and solar winds of stars within emission nebulae carve and sculpt the nebula's gas, creating caverns and pillars but also creating pressures on the gas clouds that can give rise to more starbirth.

Reflection Nebulae

Reflection nebulae reflect the light from nearby stars. The stars that illuminate them aren’t powerful enough to ionize the nebula’s gas, as with emission nebulae, but their light scatters through the gas and dust causing it to glow – like a flashlight beam shining on mist in the dark.

Because of the way light scatters when it hits the fine dust of the interstellar medium, these reflection nebulae are often bluish in color.

A reflection nebula called NGC 1999 lies close to the famous Orion Nebula, about 1,500 light-years from Earth. The nebula is illuminated by a bright, recently formed star called V380 Orionis, and the gas and dust of the nebula is material left over from that star’s formation. A second well-known reflection nebula is illuminated by the Pleiades star cluster. Most nebulae around star clusters consist of material that the stars formed from. But the Pleiades shines on an independent cloud of gas and dust, drifting through the cluster at about 6.8 miles/second (11 km/s).

Planetary Nebulae

When astronomers looked at the sky through early telescopes, they found many indistinct, cloudy forms. They called such objects "nebulae," Latin for clouds. Some of the fuzzy objects resembled planets, and these earned the name "planetary nebulae."

Today these nebulae keep the name, but we know they have nothing to do with planets. Planetary nebulae form during the death of low-mass to medium-mass stars. When such stars die, they expel their outer layers into space. These expanding shells of gas form a huge variety of unique shapes – rings, hourglasses, rectangles, and more – that show the complexity of stellar death. Astronomers are still studying how these intricate shapes form at the end of a star's life.

As the star casts off its outer layers, it leaves behind its core, which becomes a white dwarf star. White dwarf stars are objects with the approximate mass of the Sun but the size of the Earth, making them one of the densest forms of matter in the universe after black holes and neutron stars. The white dwarf star's ultraviolet radiation ionizes the gas of the planetary nebula and causes it to glow, just as stars do in emission nebulae. Our Sun is expected to form a planetary nebula at the end of its life.

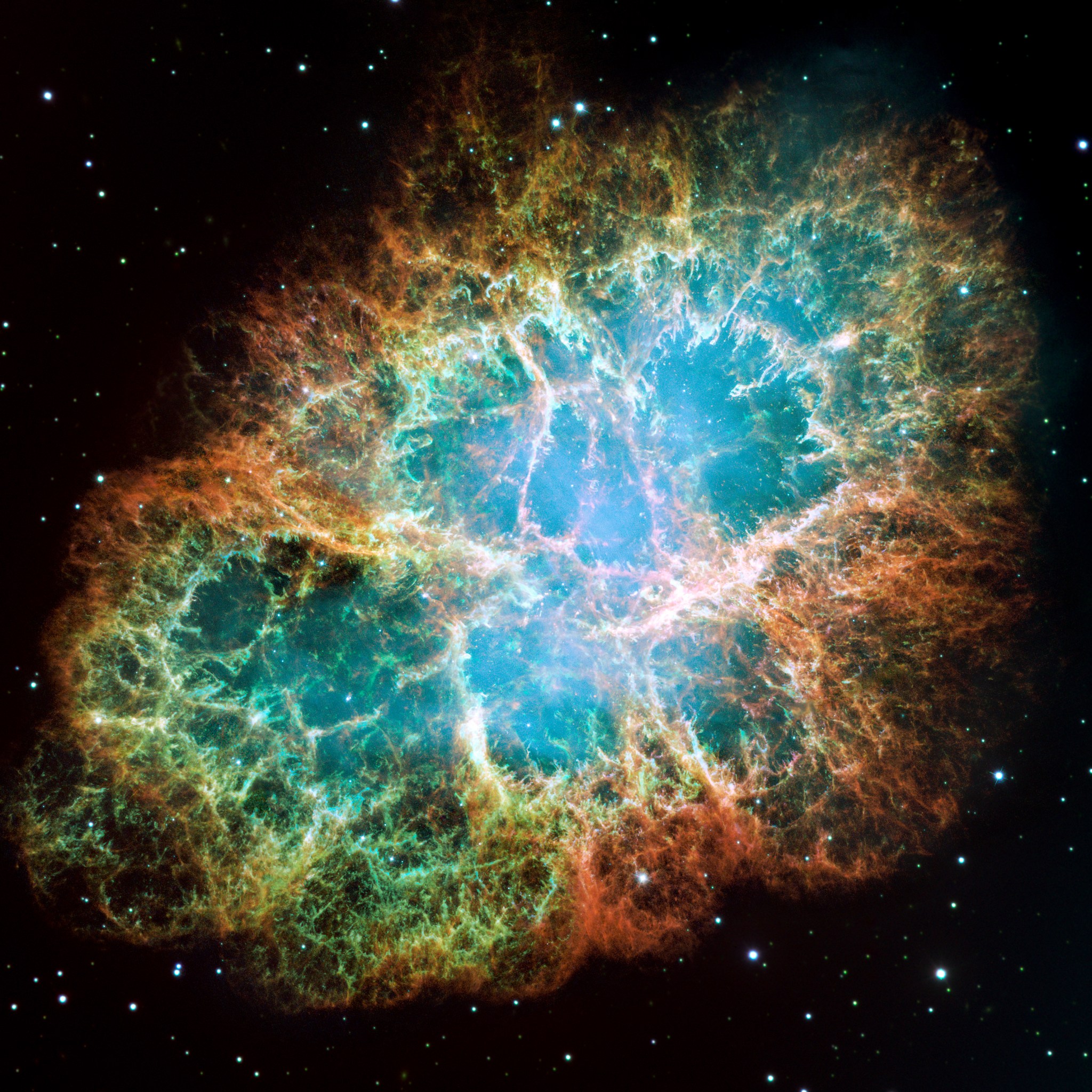

Supernova Remnants

Not all stars die gently, exhaling their outer layers into space. Some explode in a supernova, flinging their contents into space at anywhere from 9,000 to 25,000 miles (15,000 to 40,000 kilometers) per second.

When a star has a lot of mass – at least five times that of our Sun – or is part of a binary system in which a white dwarf star can gravitationally pull mass from a companion star, it can explode with the brightness of 10 billion Suns. Supernova remnants consist of material from the exploded star and any interstellar material it sweeps up in its path.

The new debris from the explosion and material ejected by the star earlier in its life collide, heating up in the shock until it glows with x-rays. Supernova remnants’ glow can also be powered by the stellar wind of a pulsar – a rapidly spinning neutron star created from the core of the exploded star. The pulsar emits electrons that interact with the magnetic field it produces, a process called synchrotron radiation, and emits X-rays, visible light and radio waves.

The Crab Nebula is an example of a supernova remnant. The explosion that created it in the year 1054 was so bright that for weeks it could be seen even in the daytime sky, and it was recorded by astronomers across the world. The material from the star is still rushing outward at around 3 million mph (4.8 million kph).

Absorption Nebulae

Absorption nebulae or dark nebulae are clouds of gas and dust that don’t emit or reflect light, but block light coming from behind them. These nebulae tend to contain large amounts of dust, which allows them to absorb visible light from stars or nebulae beyond them. Astronomer William Herschel, discussing these seemingly empty spots in the late 1700s, called them “a hole in the sky.”

Included among absorption nebulae are objects like Bok globules, small, cold clouds of gas and dense cosmic dust. Some Bok globules have been found to have warm cores, which would be caused by star formation inside, and further observation has indicated the presence of multiple stars of varying ages, suggesting a slow, ongoing star formation process.

Hubble's Nebulae Gallery

Explore More

Read about Hubble's latest discoveries.

In the vast tapestry of the universe, most galaxies shine brightly across cosmic time and space. Yet a rare class…

This stunning image from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope reveals a dramatic interplay of light and shadow in the Egg Nebula,…

This NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope image features an uncommon galaxy with a striking appearance. NGC 7722 is a lenticular galaxy located about…