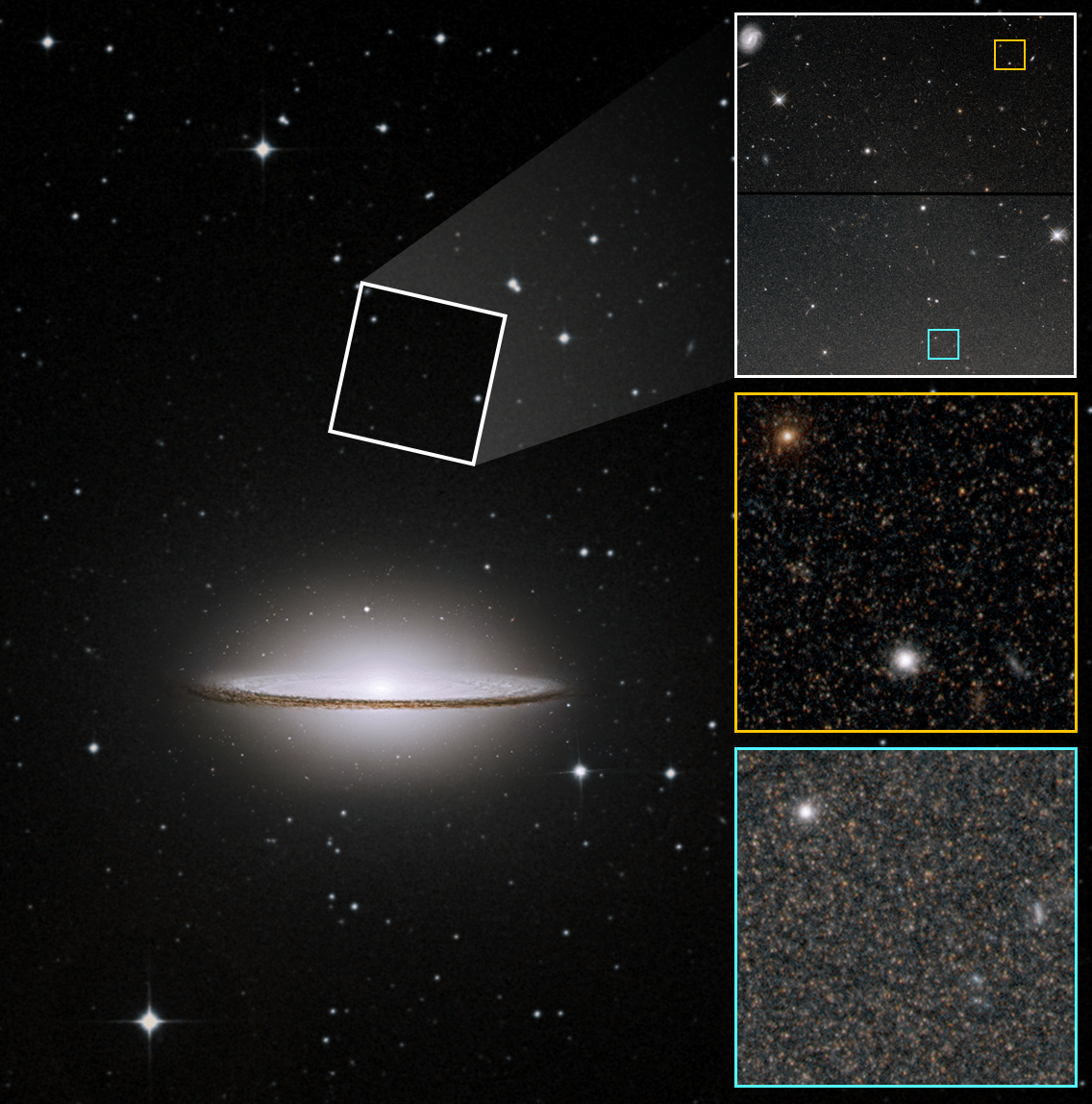

Surprising new data from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope suggests the smooth, settled "brim" of the Sombrero galaxy's disk may be concealing a turbulent past. Hubble's sharpness and sensitivity resolves tens of thousands of individual stars in the Sombrero's vast, extended halo, the region beyond a galaxy's central portion, typically made of older stars. These latest observations of the Sombrero are turning conventional theory on its head, showing only a tiny fraction of older, metal-poor stars in the halo, plus an unexpected abundance of metal-rich stars typically found only in a galaxy's disk, and the central bulge. Past major galaxy mergers are a possible explanation, though the stately Sombrero shows none of the messy evidence of a recent merger of massive galaxies.

"The Sombrero has always been a bit of a weird galaxy, which is what makes it so interesting," said Paul Goudfrooij of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), Baltimore, Maryland. "Hubble's metallicity measurements (i.e., the abundance of heavy elements in the stars) are another indication that the Sombrero has a lot to teach us about galaxy assembly and evolution."

"Hubble's observations of the Sombrero's halo are turning our generally accepted understanding of galaxy makeup and metallicity on its head," added co-investigator Roger Cohen of STScI.

Long a favorite of astronomers and amateur sky watchers alike for its bright beauty and curious structure, the Sombrero galaxy (M104) now has a new chapter in its strange story — an extended halo of metal-rich stars with barely a sign of the expected metal-poor stars that have been observed in the halos of other galaxies. Researchers, puzzling over the data from Hubble, turned to sophisticated computer models to suggest explanations for the perplexing inversion of conventional galactic theory. Those results suggest the equally surprising possibility of major mergers in the galaxy's past, though the Sombrero's majestic structure bears no evidence of recent disruption. The unusual findings and possible explanations are published in the Astrophysical Journal.

"The absence of metal-poor stars was a big surprise," said Goudfrooij, "and the abundance of metal-rich stars only added to the mystery."

In a galaxy's halo astronomers expect to find earlier generations of stars with less heavy elements, called metals, as compared to the crowded stellar cities in the main disk of a galaxy. Elements are created through the stellar "lifecycle" process, and the longer a galaxy has had stars going through this cycle, the more element-rich the gas and the higher-metallicity the stars that form from that gas. These younger, high-metallicity stars are typically found in the main disk of the galaxy where the stellar population is denser — or so goes the conventional wisdom.

Complicating the facts is the presence of many old, metal-poor globular clusters of stars. These older, metal-poor stars are expected to eventually move out of their clusters and become part of the general stellar halo, but that process seems to have been inefficient in the Sombrero galaxy. The team compared their results with recent computer simulations to see what could be the origin of such unexpected metallicity measurements in the galaxy's halo.

The results also defied expectations, indicating that the unperturbed Sombrero had undergone major accretion, or merger, events billions of years ago. Unlike our Milky Way galaxy, which is thought to have swallowed up many small satellite galaxies in so-called "minor" accretions over billions of years, a major accretion is the merger of two or more similarly massive galaxies that are rich in later-generation, higher-metallicity stars.

The satellite galaxies only contained low-metallicity stars that were largely hydrogen and helium from the big bang. Heavier elements had to be cooked up in stellar interiors through nucleosynthesis and incorporated into later-generation stars. This process was rather ineffective in dwarf galaxies such as those around our Milky Way, and more effective in larger, more evolved galaxies.

The results for the Sombrero are surprising because its smooth disk shows no signs of disruption. By comparison, numerous interacting galaxies, like the iconic Antennae galaxies, get their name from the distorted appearance of their spiral arms due to the tidal forces of their interaction. Mergers of similarly massive galaxies typically coalesce into large, smooth elliptical galaxies with extended halos — a process that takes billions of years. But the Sombrero has never quite fit the traditional definition of either a spiral or an elliptical galaxy. It is somewhere in between — a hybrid.

For this particular project, the team chose the Sombrero mainly for its unique morphology. They wanted to find out how such "hybrid" galaxies might have formed and assembled over time. Follow-up studies for halo metallicity distributions will be done with several galaxies at distances similar to that of the Sombrero.

The research team looks forward to future observatories continuing the investigation into the Sombrero's unexpected properties. The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), with a field of view 100 times that of Hubble, will be capable of capturing a continuous image of the galaxy's halo while picking up more stars in infrared light. The James Webb Space Telescope will also be valuable for its Hubble-like resolution and deeper infrared sensitivity.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA (European Space Agency). NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington, D.C.