Analyzing the images and colors of some of the most distant galaxies in the universe, as first observed nearly a year ago when NASA's Hubble Space Telescope made its deepest view of the universe (called the Hubble Deep Field), a team of astronomers is uncovering intriguing new evidence the big bang was followed by a stellar "baby boom."

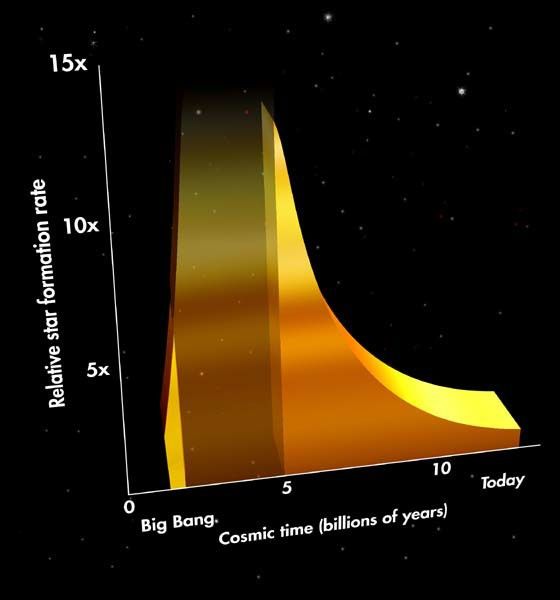

Hubble's unprecedented measurement of the rate of starbirth in remote galaxies, which existed when the universe was less than 10 percent its current age, supports the emerging view that the early universe had an active, dynamic youth where stars formed out of dust and gas at a ferocious rate.

The consequences are that most of the stars the universe will ever make have already been formed, and the universe now contains largely "mid-life" aging stars.

The Hubble results are helping to fill in the blanks in our understanding of the time between the early cooling of the universe to form matter (detected as the cosmic microwave background radiation) and the emergence of stars and galaxies.

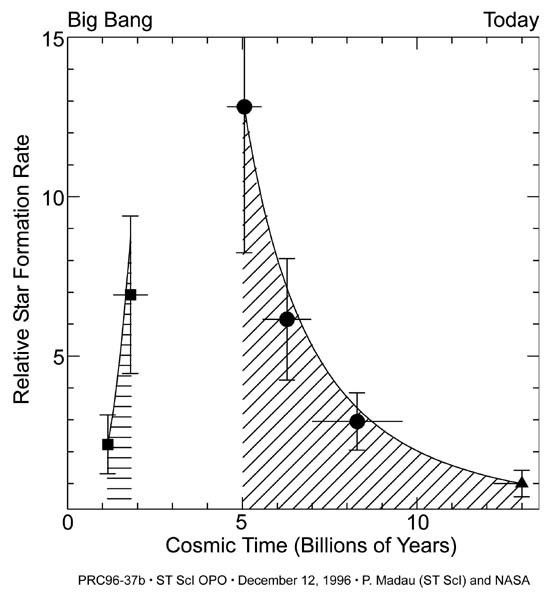

"The Hubble findings, together with ground-based data, offer a first glimpse back to the cosmic history of star formation and direct visual evidence that starbirth peaked about three billion years after the big bang," says Piero Madau of the Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Maryland. "This means that we are witnessing the birth of most of the stars which exist today." Our Sun is a "late boomer" because it was born about five billion years ago, toward the tail-end of the stellar population explosion.

The results, based on work by Madau, Henry Ferguson, Mark Dickinson, Andrew Fruchter (Space Telescope Science Institute), Mauro Giavalisco (Carnegie Observatories), and Charles Steidel (Palomar Observatory, California Institute of Technology), will appear in the December 15 issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The researchers first estimated approximate galaxy distances by comparing HDF exposures taken through different color filters. Numerous galaxies seen in the HDF in visible light abruptly vanish when viewed in ultraviolet light. This is because hydrogen, located within the distant galaxies and in the huge volume of intergalactic space light traverses, absorbs the ultraviolet light from distant objects. The cumulative effect of the absorption is to make these galaxies essentially vanish in the ultraviolet, like distant streetlights fading away in a morning haze. This provides a unique way to distinguish very distant galaxies from nearby objects. The technique has already been tested and proven with spectroscopic redshifts taken with the Keck telescope, in Hawaii.

Using this technique, the researchers have identified at least 15 galaxies which existed when the universe was between 8% and 10% its current age (redshift 3.5 to 4.5), and more than 70 galaxies which existed when the universe was between 10% and 20% its current age. "There could be more of these faint galaxies among the 3,000 in the HDF field," says Madau, "but our technique is only applicable to the 500 or so brightest galaxies."

After pinpointing the galaxies, the researchers calculated the rate of starbirth by measuring the total amount of ultraviolet light radiated, which is known to be produced by hot, massive stars within them. Because such stars are short lived, their very presence indicates that they lie at a site of recent star formation, and are therefore an excellent tracer of starbirth activity. (Due to the expansion of the universe, the ultraviolet light is shifted to visible wavelengths in the HDF images taken with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2).

The astronomers find that stars were forming few times more rapidly than they are at the present epoch. The researchers caution, however, that their estimates should only be regarded as a lower limit, as their search technique cannot find dusty galaxies which may house a significant amount of starlight reddened by scattering due to interstellar dust.

The Hubble results complement conclusions reached from the extensive, ground-based Canada-France Redshift Survey (CFRS), a project led by astronomer Simon Lilly (University of Toronto), which measured the star formation rates for hundreds of galaxies out to a distance of about 9 billion light-years. The CFRS results showed that stellar birth rates in the universe as a whole are relatively low now, but were substantially higher in the past.

Like bookends, the ground-based and Hubble data put brackets around the period where starbirth probably peaked at a rate ten times higher than today. Intriguingly, the peak in the rate of star formation appears to be close to the well-known peak in the abundance of quasars (extremely energetic cores of galaxies) in the early universe.

The HDF results also support theoretical work by Michael Fall (STScI) and Yichuan Pei (Johns Hopkins University) who had previously estimated the star formation history of the universe based on the evolution of the gas and metal content of galaxies as inferred from quasar absorption-line measurements.

"The correspondence between the Hubble observations and the absorption-line observations is gratifying. This enables us to relate the HDF result to other phenomena at high redshifts," says Michael Fall of STScI.

The researchers hope to use the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS), scheduled to be installed in Hubble during the February 1997 Space Shuttle servicing mission, to do follow-up observations. The STIS ultraviolet capabilities will extend the searches for distant galaxies five times fainter than possible with the existing HDF data.

The Hubble Space Telescope spent ten days in December 1995 observing a single tiny patch of sky near the Big Dipper. These observations resulted in the deepest image of the sky, revealing galaxies fainter than had ever been seen before. The striking full-color image of the distant universe was unveiled at the American Astronomical Society Meeting in January 1996, and for the last year has been the subject of intense study worldwide.