NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has helped solve a two-decade-old cosmic mystery by showing that mysterious clouds of hydrogen in space may actually be vast halos of gas surrounding galaxies.

"This conclusion runs contrary to the longstanding belief that these clouds occur in intergalactic space," says Ken Lanzetta of the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

The existence of such vast halos, which extend 20 times farther than the diameter of a galaxy, might provide new insights into the evolution of galaxies and the nature of dark matter – an apparently invisible form of matter that surrounds galaxies.

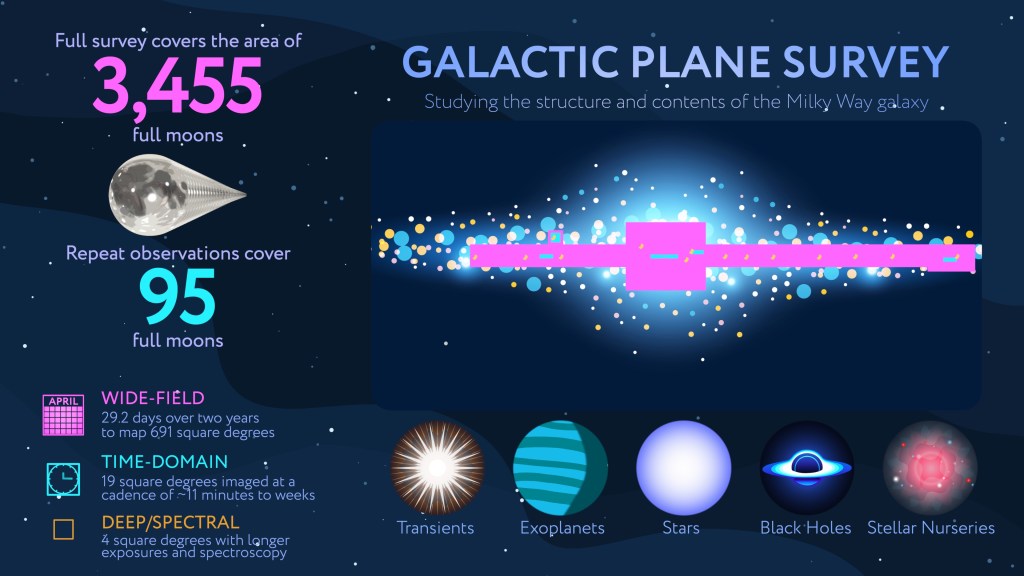

The possibility of galaxy halos was first proposed in 1969 by John Bahcall and Lyman Spitzer of the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ. Previous observations with ground-based telescopes, the International Ultraviolet Explorer satellite, and Hubble have suggested that these clouds might be galaxy halos. However, the latest results are the most definitive finding yet, says Lanzetta, because they come from a large sample of 46 galaxies.

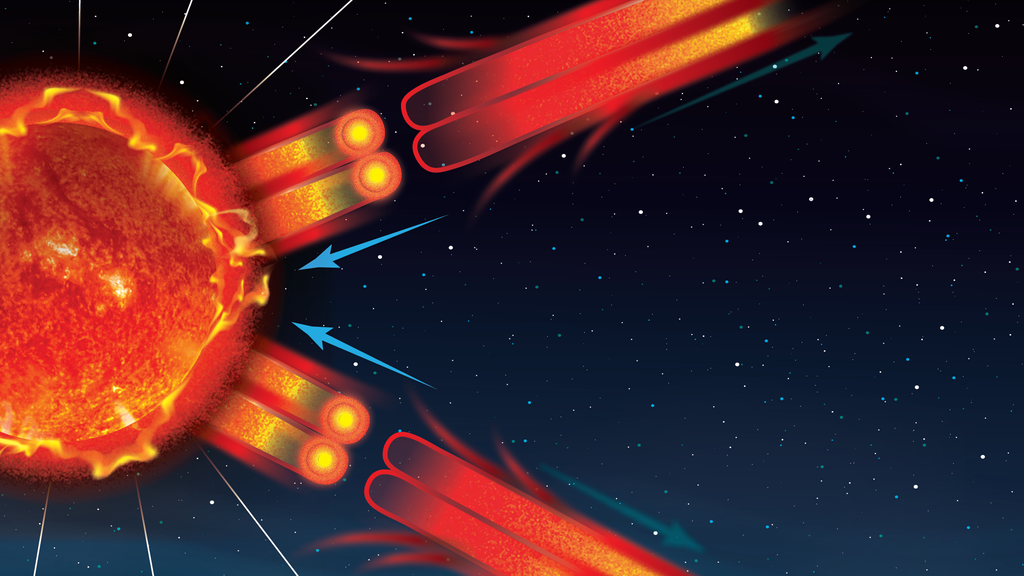

For the past two decades, observations with ground-based telescopes have shown that the light from distant quasars (the bright cores of active galaxies) is affected by intervening gas clouds. These clouds are invisible, but betray their presence by absorbing certain frequencies, or colors, of a quasar's light. When a quasar's light is spread out into a spectrum, the missing wavelengths appear as a complex "thicket" of absorption features. Ground-based observations also showed that the number of these clouds rapidly rises out to greater distance. One possible explanation was that these were primordial clumps of gas that dissipated over time.

However, in 1991, independent observations made with Hubble's Faint Object Spectrograph and Goddard High Resolution Spectrograph instruments detected more than a dozen hydrogen clouds within less than a billion light-years of our galaxy. These clouds could not be detected previously because they are only visible in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, which is inaccessible with ground-based telescopes. This gave astronomers a powerful opportunity to further test the halo theory by imaging nearby galaxies and attempting to match them with nearby clouds.

Lanzetta, David Bowen of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), Baltimore, MD, David Tyler of the University of California at San Diego, and John Webb of the University on New South Wales, Australia, attempted to match galaxies and clouds by first collecting Hubble archival data on six quasars. Next, using telescopes at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, the Anglo Australian Observatory, the Lick Observatory and the Isaac Newton Telescope, they identified galaxies near the clouds and measured distances. In the majority of cases they found galaxies within about 500,000 light-years of the clouds.

"These results are a surprise. We have never seen these halos in the local universe," said David Bowen of STScI.

The results explain why so many clouds are seen at greater distances: the light from distant quasars was more likely to pass through a galaxy's halo because the halo is so large.

These results appear in the April 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal. The researchers plan to extend their research to a larger sample of galaxy/cloud pairs.