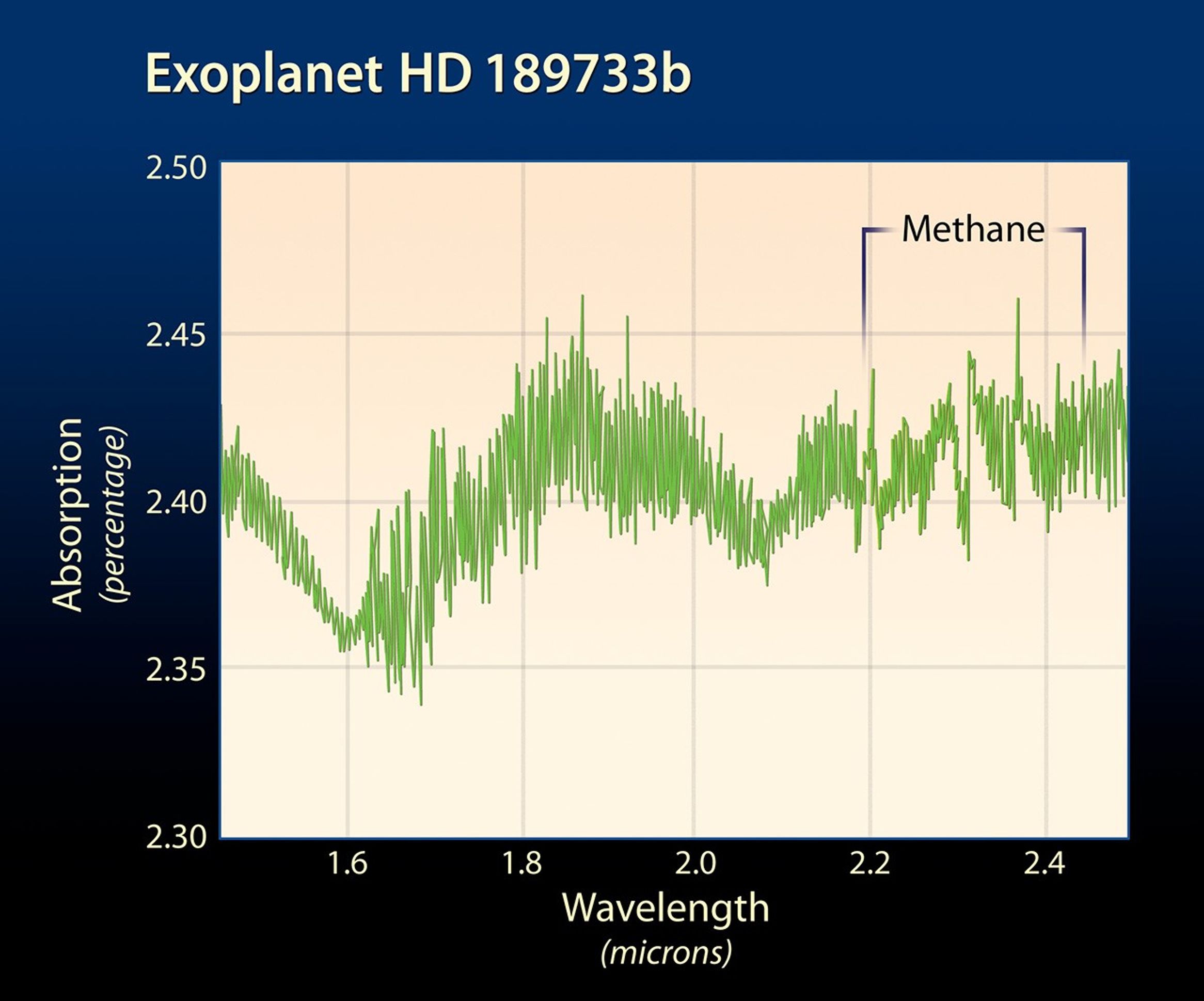

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope (HST) has made the first detection ever of an organic molecule in the atmosphere of a Jupiter-sized planet orbiting another star. This breakthrough is an important step in eventually identifying signs of life on a planet outside our solar system.

The molecule found by Hubble is methane, which under the right circumstances can play a key role in prebiotic chemistry – the chemical reactions considered necessary to form life as we know it.

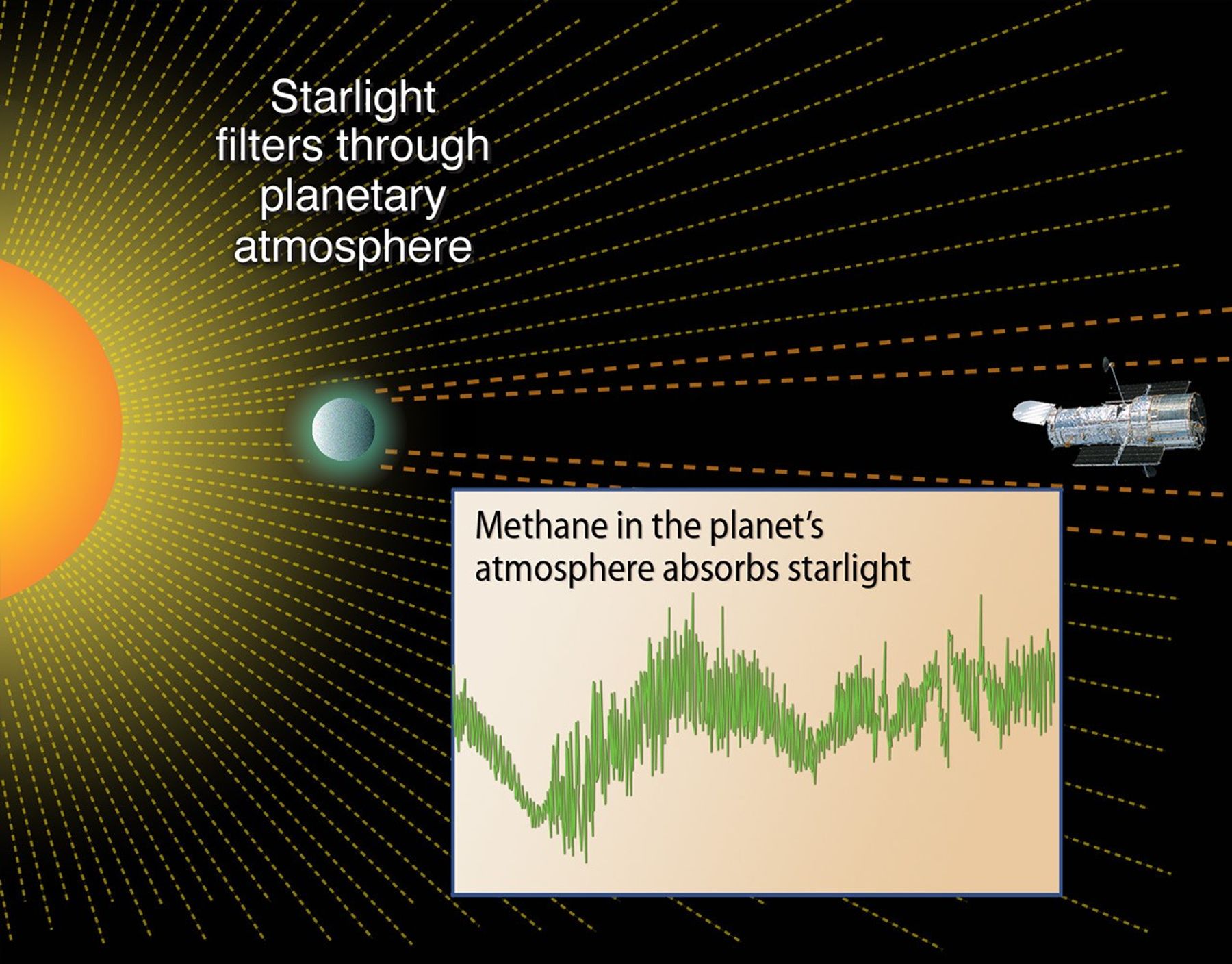

This discovery proves that Hubble and upcoming space missions, such as NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, can detect organic molecules on planets around other stars by using spectroscopy, which splits light into its components to reveal the "fingerprints" of various chemicals.

"This is a crucial stepping stone to eventually characterizing prebiotic molecules on planets where life could exist," said Mark Swain of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, Calif., who led the team that made the discovery. Swain is lead author of a paper appearing in the March 20 issue of Nature.

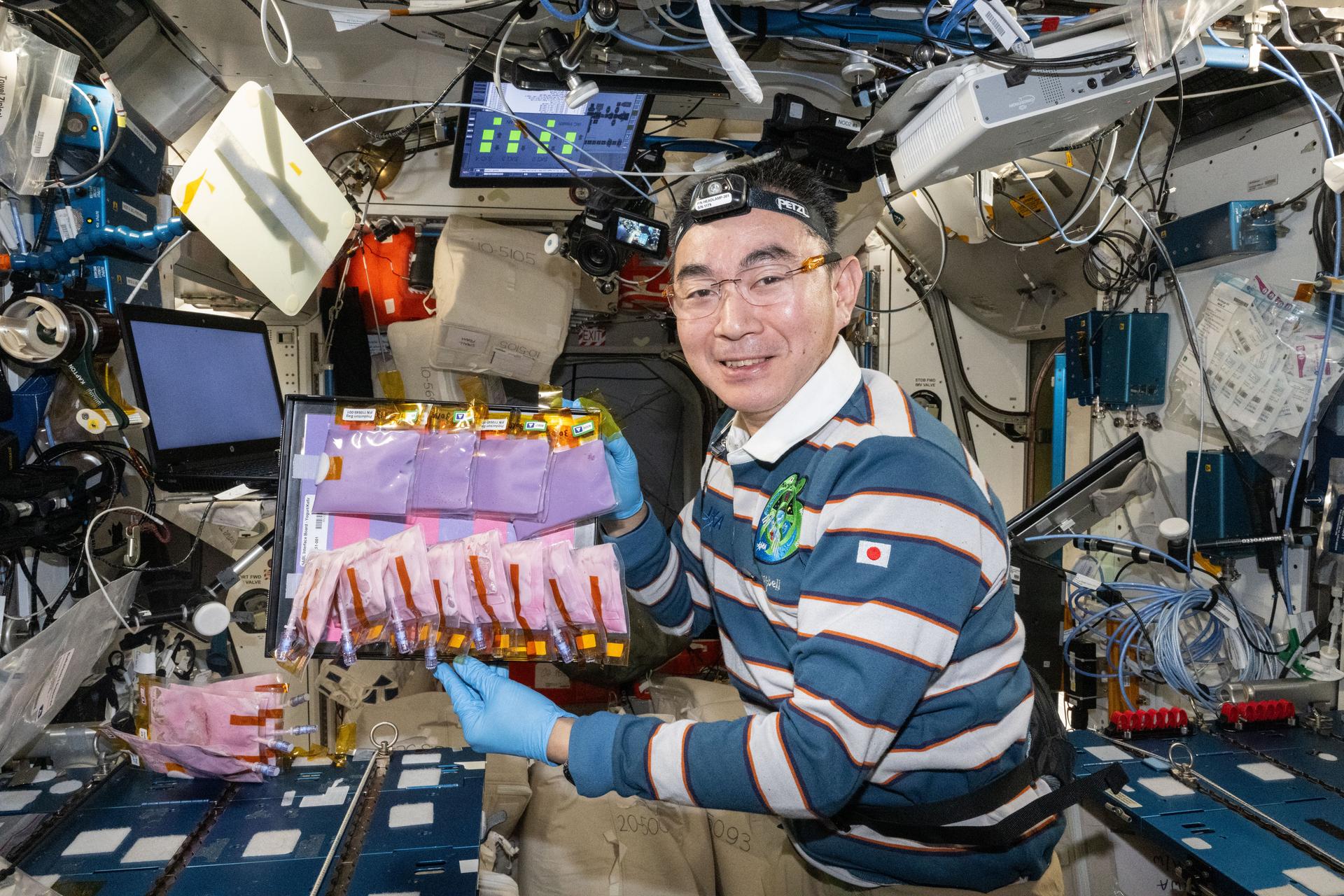

The discovery comes after extensive observations made in May 2007 with Hubble's Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer (NICMOS). It also confirms the existence of water molecules in the planet's atmosphere, a discovery made originally by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope in 2007. "With this observation there is no question whether there is water or not – water is present," said Swain.

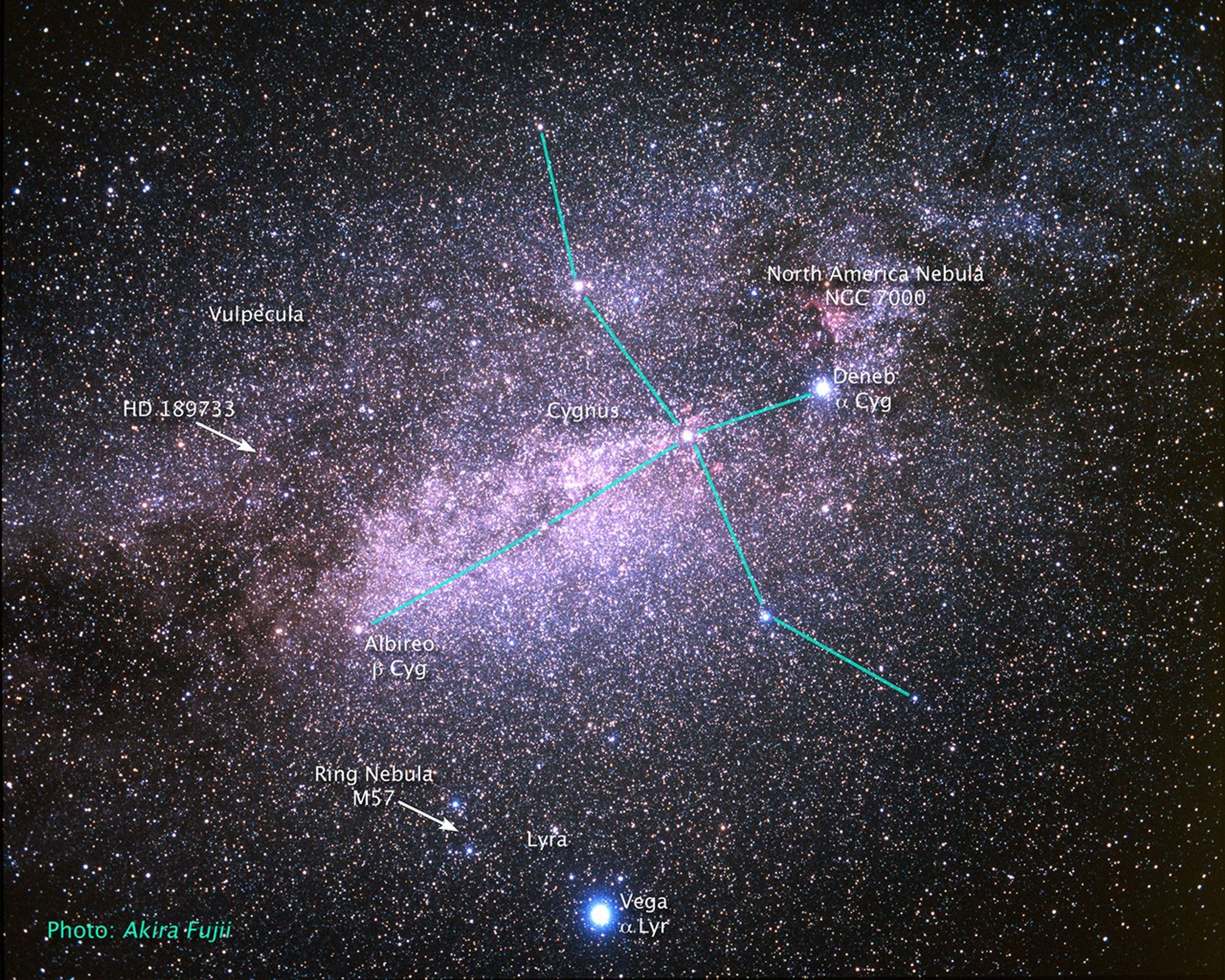

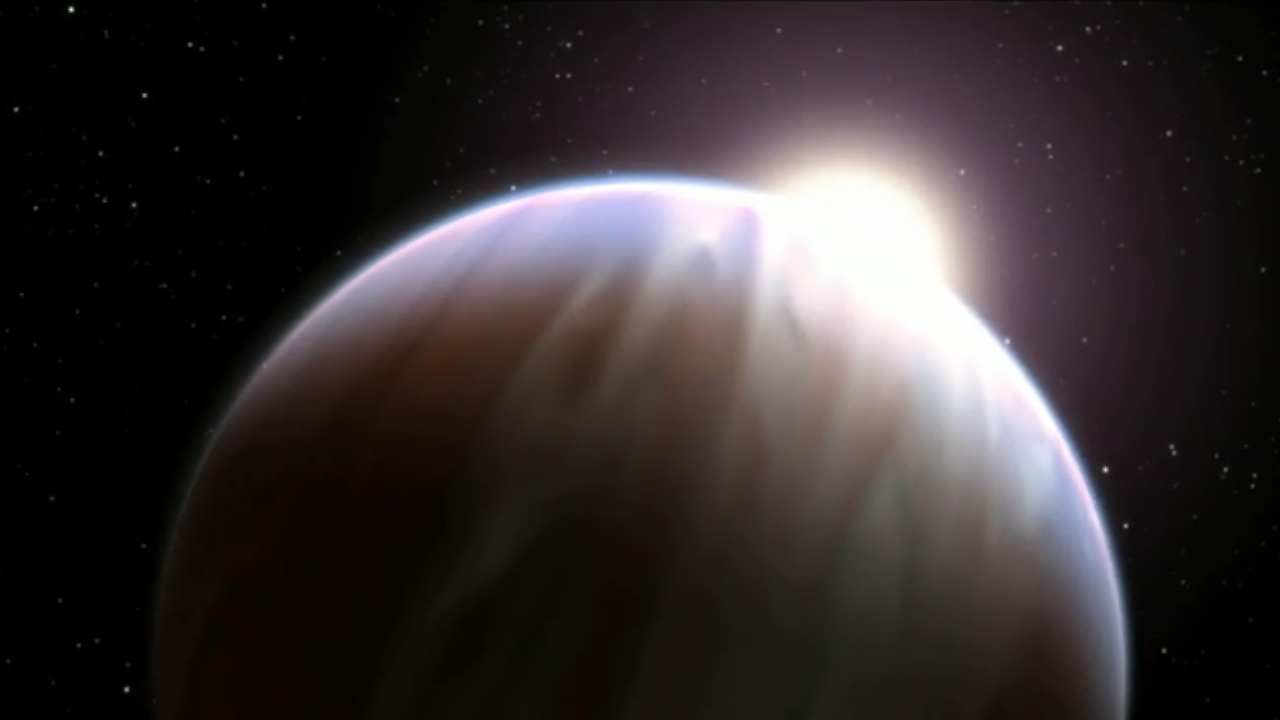

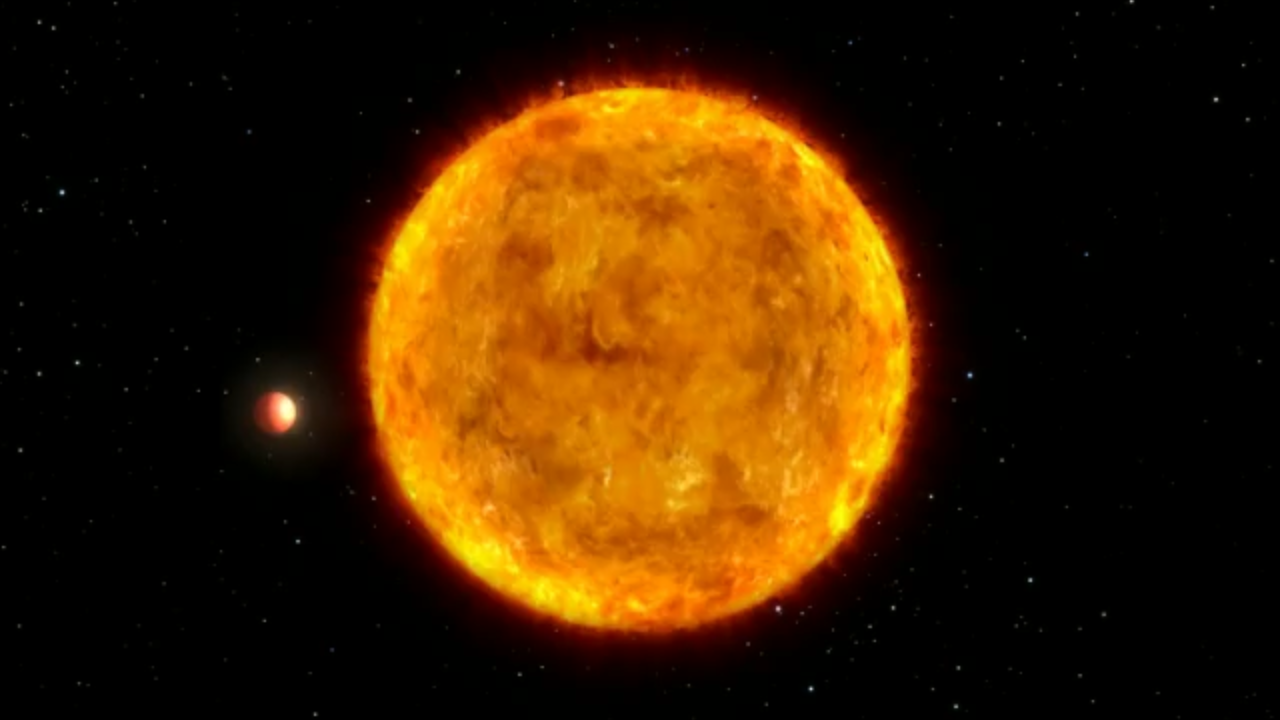

The planet now known to have methane and water is located 63 light-years away in the constellation Vulpecula. Called HD 189733b, the planet is so massive and so hot it is considered an unlikely host for life. HD 189733b, dubbed a "hot Jupiter," is so close to its parent star it takes just over two days to complete an orbit. These objects are the size of Jupiter but orbit closer to their stars than the tiny innermost planet Mercury in our solar system. HD 189733b's atmosphere swelters at 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit, about the same temperature as the melting point of silver.

Though the star-hugger planet is too hot for life as we know it, "this observation is proof that spectroscopy can eventually be done on a cooler and potentially habitable Earth-sized planet orbiting a dimmer red dwarf-type star," Swain said. The ultimate goal of studies like these is to identify prebiotic molecules in the atmospheres of planets in the "habitable zones" around other stars, where temperatures are right for water to remain liquid rather than freeze or evaporate away.

The observations were made as the planet HD 189733b passed in front of its parent star in what astronomers call a transit. As the light from the star passed briefly through the atmosphere along the edge of the planet, the gases in the atmosphere imprinted their unique signatures on the starlight from the star HD 189733.

The astronomers were surprised to find that the planet has more methane than predicted by conventional models for "hot Jupiters." "This indicates we don't really understand exoplanet atmospheres yet," said Swain.

"These measurements are an important step to our ultimate goal of determining the conditions, such as temperature, pressure, winds, clouds, etc., and the chemistry on planets where life could exist. Infrared spectroscopy is really the key to these studies because it is best matched to detecting molecules," said Swain.

Swain's co-authors on the paper include Gautam Vasisht of JPL and Giovanna Tinetti of University College, London/European Space Agency.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION: THE HUNT FOR LIFE ON OTHER WORLDS

Methane gas rises from rotting garbage on Earth, and droplets of liquid methane rain down on Saturn's moon Titan. Even the planets Neptune and Uranus have an abundance of methane in their atmospheres. That's why they appear blue-green.

Methane is a common chemical in our solar system, generated by living organisms and natural, non-living things.

So why are astronomers delighted to find methane in the atmosphere of a faraway planet orbiting another star? The detection was made with the Near-Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer aboard NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. The Jupiter-sized planet, called HD 189733b, is too hot to sustain life because it is too close to its parent star. The gas-giant planet completes an orbit in just over two days. Life as we know it could not exist on a planet whose atmosphere is a scorching 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit, about the temperature it takes to melt silver.

But astronomers say this detection offers hope that they will one day be able to probe the atmospheres of cooler, more hospitable worlds. Finding methane in the atmosphere of HD 189733b demonstrates that astronomers can successfully use spectroscopy to detect organic molecules on planets around other stars. Spectroscopy splits light into its component colors to reveal the "fingerprints" of various chemicals.

"This observation is one of the first steps in the search for life on another planet," says astrophysicist Marc Kuchner of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center's Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics Laboratory. "We need to study the chemistry in a planet's atmosphere in order to determine whether the planet could harbor life."

As the HD 189733b observation shows, organic chemicals like methane can be produced by chemical processes that do not require life. On Titan, Saturn's largest moon, the abundance of methane may have been generated by a geological process between water and rock deep inside the moon. Even on Earth, not all the methane is the byproduct of life processes. A small amount of the gas is produced by volcanism.

Discovering methane on an Earth-like world in a habitable zone around a star – a location where liquid water could exist on the planet's surface – would be promising, Kuchner says.

What is the blueprint of life?

In their search for habitable planets, scientists have only one blueprint of life: Earth. Shaped, in part, by biological evolution, our planet has just the right balance of methane, oxygen, nitrogen, and water in its atmosphere. In addition, Earth orbits at just the right distance from its star, at a point where temperatures are ideal for liquid oceans to form and life therefore to thrive. But that does not rule out the possibility of other blueprints of life.

"There could be other ingredients and conditions for life that we don't know about," Kuchner says. "But how do we know if we have found a life-bearing planet if it is different from Earth?"

In fact, scientists may have missed signs of life on Mars when the Viking spacecraft visited the Red Planet more than 30 years ago. In 2007, a scientist at the University of Giessen in Germany announced that a reevaluation of Martian data suggests it may contain microbial life. The researcher said soil collected by Viking may have shown signs of a weird life form based on hydrogen peroxide on the subfreezing, dry Martian surface. The tests conducted by instruments onboard the spacecraft, however, may have killed any Mars organisms, the German researcher and other scientists claim. The Viking spacecraft was equipped to analyze soil samples for indications of Earth-like living matter that thrived in water and warm temperatures. The Mars organisms had evolved to adapt to a frigid, dry environment.

Modeling life-bearing planets

One way to study alien worlds for life is to develop models of planetary atmospheres in a lab. The Virtual Planetary Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology's Spitzer Science Center is one such "planetary model factory." The research is driven by the idea that not all life is going to metabolize food and energy exactly as life on Earth does. So they are cooking up alternative environments on distant worlds where life could form.

The changing face of planets

Planets also can change over time. Earth is one example. Over the last 4.6 billion years, the amount of oxygen in Earth's atmosphere has changed drastically over billions of years. Today's oxygen levels are relatively high, but billions of years ago, oxygen did not exist on the planet.

Back then, the first homesteaders, members of a family of single-cell microorganisms called archaea, thrived in Earth's hostile environment. One type of archaeon was a methanogen, which emitted methane as a byproduct of its life process. Multi-cellular life began forming about 500 million years ago, when the oxygen level in Earth's atmosphere rose rapidly. The increase was probably due to blue-green algae that produced oxygen as a waste byproduct.

Looking for Earth's vital signs

Even if scientists discover the right mix of chemicals for a habitable planet, they may not be able to rule out whether non-biological processes created them.

In 1990 noted astronomer Carl Sagan conducted a test on whether scientists could prove if life exists on Earth. He and several colleagues used the Galileo spacecraft, which was en route to Jupiter, to take snapshots of Earth to look for evidence of life.

The spacecraft's instruments detected far more oxygen, methane, and nitrous oxide in Earth's atmosphere than a lifeless planet would normally have. Other important ingredients of life discovered by Galileo were water in its solid, liquid, and gaseous forms and chlorophyll, which plants use for photosynthesis, covering some land surfaces. "Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that widespread biological activity now exists, of all the worlds in this solar system, only on Earth," Sagan and his colleagues wrote in their paper, published in the journal Nature.

He wondered, however, whether people from alien worlds would come to the same conclusion.

"But how plausible a world covered with carbon-fixing photosynthetic organisms, using water as the electron donor and generating a massive (and poisonous) oxygen atmosphere, might be to observers from a very different world is an open question." The most convincing clue for Earthly life was the modulated radio waves emanating from our planet's surface.

"On the basis of these observations, a strong case can be made that the signals are generated by an intelligent form of life on Earth," Sagan wrote. The researchers also noted that as recently as a century ago, these signals, and hence intelligent life, would not have been detected by a passing spaceship.

Looking beyond our solar system

If the Galileo analysis of Earth is any measure, then proving the existence of life on a distant world will be a challenging task for future telescopes. "How can you take a spectrum of an extrasolar planet's atmosphere and know for certain whether there is life or not?" Kuchner asks. "There is probably a huge range of atmospheres on extrasolar planets. Some probably have biomarkers of life, but those biosignatures are not a 'slam-dunk' for life on those planets. I think life on another planet may not be confirmed unless we go there."

One way to bolster evidence for habitable planets is to build up an inventory of the atmospheres of many distant worlds so that astronomers can make comparisons to better determine the ones where life could exist.