When black holes collide, look out! The "kick" from an enormous burst of gravitational radiation that occurs during the collision could knock a black hole clear out of its galaxy, rather than resulting in one massive black hole, as commonly thought. New theoretical simulations by Astrophysicist David Merritt of the Rochester Institute of Technology, and colleagues, determined how much kick the black holes get from the mergers and then compared this with the escape velocities from galaxies that could harbor merged black holes. They found that larger and brighter galaxies have stronger gravitational fields and would require a bigger kick to eject a black hole than the smaller systems. Likewise, less forceful impacts could jar the black hole out of its home at the center of a galaxy, only to later rebound back into position. The researchers say that the kicks call into question theories that would grow supermassive black holes from hierarchical mergers of smaller black holes, starting in the early universe.

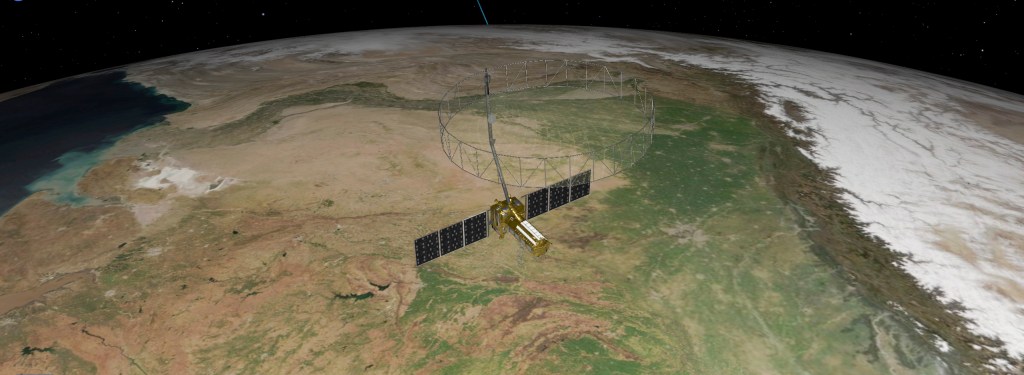

The researchers relied on a series of Hubble Space Telescope discoveries to reach this conclusion. Hubble has previously shown that supermassive black holes are common in galaxies. Hubble has also shown that galaxies were smaller long ago. This means that the black hole kicks would easily have removed the black holes from smaller galaxies. "It's more likely that supermassive black holes attained most of their mass through the accretion of gas. Mergers with other black holes only took place after the galaxies had reached roughly their current sizes," says Merritt.

Merritt notes that while there is no observational evidence that the kicks have taken place, they could explain the lack of black holes in dwarf galaxies and globular clusters. He contends that the best chance of finding direct evidence would be locating a black hole shortly after the kick occurs, perhaps in a galaxy that has recently undergone a merger with another galaxy. "You would see an off-center black hole that hasn't quite made its way back to the center yet," he says. "Even though the probability of observing this is low, now that astronomers know what to look for, I wouldn't be surprised if someone finds one eventually."

The science team's article, "Consequences of Gravitational Radiation Recoil," has been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal. The article was supported by funding from the Space Telescope Science Institute and appears online.