Taking advantage of a total lunar eclipse, astronomers using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have detected Earth's own brand of sunscreen – ozone – in our atmosphere. This method simulates how astronomers and astrobiology researchers will search for evidence of life beyond Earth by observing potential "biosignatures" on exoplanets (planets around other stars).

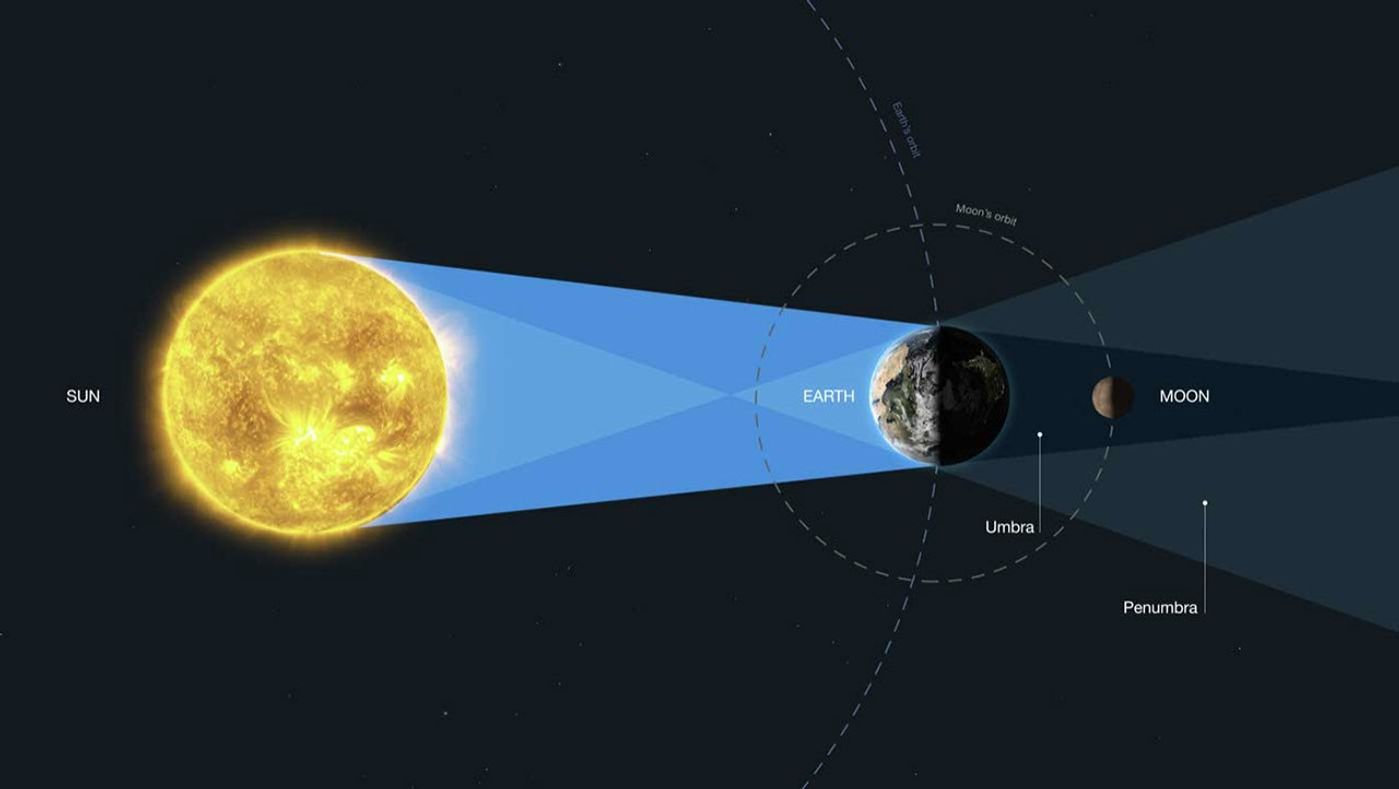

Hubble did not look at Earth directly. Instead, the astronomers used the Moon as a mirror to reflect sunlight, which had passed through Earth's atmosphere, and then reflected back towards Hubble. Using a space telescope for eclipse observations reproduces the conditions under which future telescopes would measure atmospheres of transiting exoplanets. These atmospheres may contain chemicals of interest to astrobiology, the study of and search for life.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

Though numerous ground-based observations of this kind have been done previously, this is the first time a total lunar eclipse was captured at ultraviolet wavelengths and from a space telescope. Hubble detected the strong spectral fingerprint of ozone, which absorbs some of the sunlight. Ozone is important to life because it is the source of the protective shield in Earth's atmosphere.

On Earth, photosynthesis over billions of years is responsible for our planet's high oxygen levels and thick ozone layer. That's one reason why scientists think ozone or oxygen could be a sign of life on another planet, and refer to them as biosignatures.

"Finding ozone is significant because it is a photochemical byproduct of molecular oxygen, which is itself a byproduct of life," explained Allison Youngblood of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics in Boulder, Colorado, lead researcher of Hubble's observations.

Although ozone in Earth's atmosphere had been detected in previous ground-based observations during lunar eclipses, Hubble's study represents the strongest detection of the molecule to date because ozone – as measured from space with no interference from other chemicals in the Earth's atmosphere – absorbs ultraviolet light so strongly.

Hubble recorded ozone absorbing some of the Sun's ultraviolet radiation that passed through the edge of Earth's atmosphere during a lunar eclipse that occurred on January 20 to 21, 2019. Several other ground-based telescopes also made spectroscopic observations at other wavelengths during the eclipse, searching for more of Earth's atmospheric ingredients, such as oxygen and methane.

"One of NASA's major goals is to identify planets that could support life," Youngblood said. "But how would we know a habitable or an uninhabited planet if we saw one? What would they look like with the techniques that astronomers have at their disposal for characterizing the atmospheres of exoplanets? That's why it's important to develop models of Earth's spectrum as a template for categorizing atmospheres on extrasolar planets."

Her paper is available online in The Astronomical Journal.

Sniffing Out Planetary Atmospheres

The atmospheres of some extrasolar planets can be probed if the alien world passes across the face of its parent star, an event called a transit. During a transit, starlight filters through the backlit exoplanet's atmosphere. (If viewed close up, the planet's silhouette would look like it had a thin, glowing "halo" around it caused by the illuminated atmosphere, just as Earth does when seen from space.)

Chemicals in the atmosphere leave their telltale signature by filtering out certain colors of starlight. Astronomers using Hubble pioneered this technique for probing exoplanets. This is particularly remarkable because extrasolar planets had not yet been discovered when Hubble was launched in 1990 and the space observatory was not initially designed for such experiments.

So far, astronomers have used Hubble to observe the atmospheres of gas giant planets and super-Earths (planets several times Earth's mass) that transit their stars. But terrestrial planets about the size of Earth are much smaller objects and their atmospheres are thinner, like the skin on an apple. Therefore, teasing out these signatures from Earth-sized exoplanets will be much harder.

That's why researchers will need space telescopes much larger than Hubble to collect the feeble starlight passing through these small planets' atmospheres during a transit. These telescopes will need to observe planets for a longer period, many dozens of hours, to build up a strong signal.

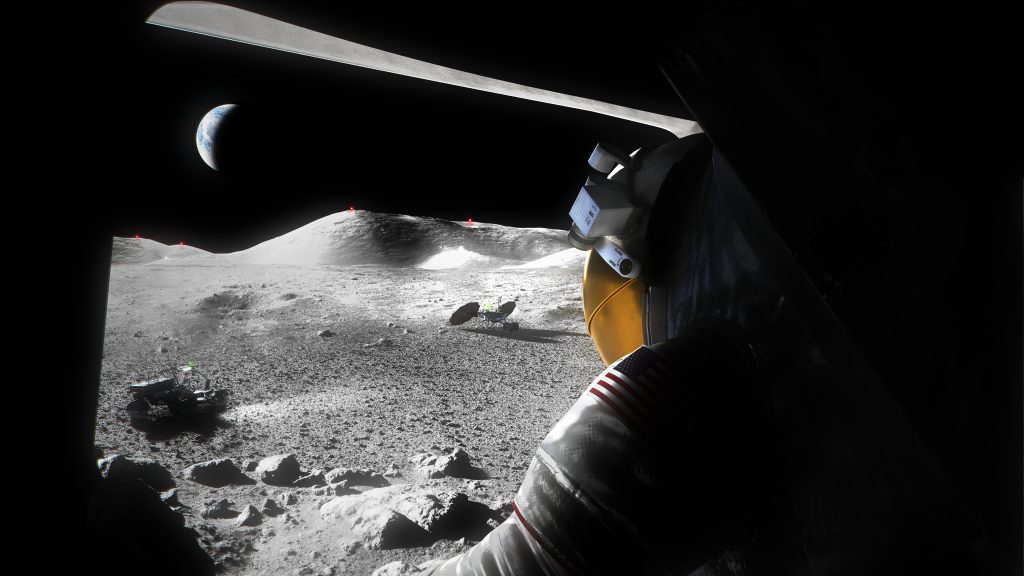

To prepare for these bigger telescopes, astronomers decided to conduct experiments on a much closer and only known inhabited terrestrial planet: Earth. Our planet's perfect alignment with the Sun and Moon during a total lunar eclipse mimics the geometry of a terrestrial planet transiting its star.

But the observations were also challenging because the Moon is very bright, and its surface is not a perfect reflector because it is mottled with bright and dark areas. The Moon is also so close to Earth that Hubble had to try and keep a steady eye on one select region, despite the Moon's motion relative to the space observatory. So, Youngblood's team had to account for the Moon's drift in their analysis.

Where There's Ozone, There's Life?

Finding ozone in the skies of a terrestrial extrasolar planet does not guarantee that life exists on the surface. "You would need other spectral signatures in addition to ozone to conclude that there was life on the planet, and these signatures cannot necessarily be seen in ultraviolet light," Youngblood said.

On Earth, ozone is formed naturally when oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere is exposed to strong concentrations of ultraviolet light. Ozone forms a blanket around Earth, protecting it from harsh ultraviolet rays.

"Photosynthesis might be the most productive metabolism that can evolve on any planet, because it is fueled by energy from starlight and uses cosmically abundant elements like water and carbon dioxide," said Giada Arney of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, a co-author of the science paper. "These necessary ingredients should be common on habitable planets."

Seasonal variability in the ozone signature also could indicate seasonal biological production of oxygen, just as it does with the growth seasons of plants on Earth.

But ozone can also be produced without the presence of life when nitrogen and oxygen are exposed to sunlight. To increase confidence that a given biosignature is truly produced by life, astronomers must search for combinations of biosignatures. A multiwavelength campaign is needed because each of the many biosignatures are more easily detected at wavelengths specific to those signatures.

"Astronomers will also have to take the developmental stage of the planet into account when looking at younger stars with young planets. If you wanted to detect oxygen or ozone from a planet similar to the early Earth, when there was less oxygen in our atmosphere, the spectral features in optical and infrared light aren't strong enough," Arney explained. "We think Earth had low concentrations of ozone before the mid-Proterozoic geological period (between roughly 2.0 billion to 0.7 billion years ago) when photosynthesis contributed to the build up of oxygen and ozone in the atmosphere to the levels we see today. But because the ultraviolet-light signature of ozone features is very strong, you would have a hope of detecting small amounts of ozone. The ultraviolet may therefore be the best wavelength for detecting photosynthetic life on low-oxygen exoplanets."

NASA has a forthcoming observatory called the James Webb Space Telescope that could make similar kinds of measurements in infrared light, with the potential to detect methane and oxygen in exoplanet atmospheres. Webb is currently scheduled to launch in 2021.