Since its launch in April 1990, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has amassed more than 1.7 million observations. This vast archive allows researchers to develop collaborative projects that include members of the public who volunteer their time and help corral the data. These citizen scientists contribute to research through various tasks aimed at producing scientific results that researchers could not achieve without the help of volunteers. The process often begins with volunteers visiting websites designed to teach them the basic science behind the project and guide them through the process of discovery.

Because astronomy is such a visual science and Hubble's high-resolution observations provide stunning detail, most Hubble citizen science projects center around the components of Hubble images. These projects asked volunteers to identify specific features in the image, classify the type of object or objects in the image, or to find similarities between images.

Menagerie of Galaxies

One program that helped astronomers classify cosmic objects was Galaxy Zoo: Hubble, a project launched for Hubble’s 20th anniversary that built upon the Galaxy Zoo citizen science program designed to accurately classify galaxies sampled through the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). The original Galaxy Zoo included large numbers of volunteers with minimal training to visually classify more than 800,000 galaxies. Automated artificial intelligence was able to measure size, shape, color, and the basic form of galaxies, but it often missed the subtleties of galaxy shapes. These subtleties are important to astronomers trying to understand galaxy formation and evolution as well as the structure of the universe. The work of 86,000 individual volunteers provided 40.6 million individual assessments on galaxy classifications.

The Hubble project compared images of 120,000 distant galaxies from earlier in the universe. The project compared these earlier galaxy images, taken by Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys, to those seen in recent SDSS images. The research program helped astronomers better understand what influences galaxy formation and evolution.

The project revealed significant changes in the proportion of disk galaxies to elliptical galaxies depending on their redshift. Disk galaxies, like our own Milky Way, were more prominent earlier in the universe, while elliptical galaxies are more prevalent now. Researchers also found an increasing number of galaxies dominated by smaller clumps. They concluded that the galaxies are in the process of growing and obtaining mass through a combination of merging and star formation.

This video explores how astronomers classify galaxies. Hubble's namesake, astronomer Edwin Hubble, developed a basic system for classifying galaxies that astronomers still use today.

Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center; Lead Producer: Miranda Chabot; Writer: Andrea Gianopoulos

Photo-bombing Asteroids

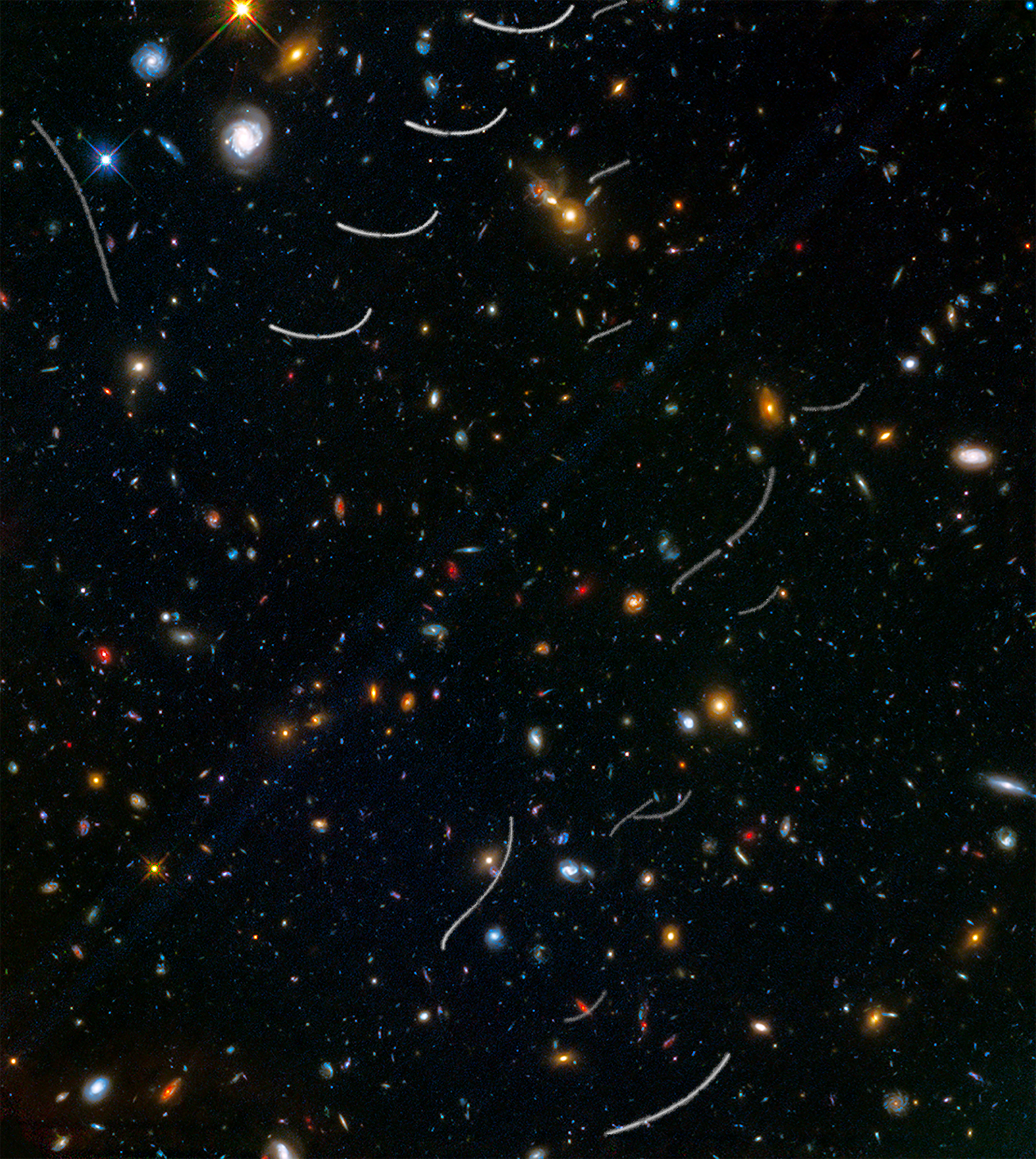

Closer to home, one Hubble citizen science project focused on photo-bombing asteroids in Hubble images. On International Asteroid Day in June 2019, an international team of astronomers launched Hubble Asteroid Hunter, a citizen science project to identify asteroids in archival Hubble data.

The project examined more than 37,000 composite images spanning 19 years. These images were taken with Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Camera 3 between April 2002 and March 2021 with typical observation times of 30 minutes. Nearly 13,000 volunteers contributed to the classification of these images, finding asteroid trails that appeared as curved lines or streaks, as well as other astronomical objects like gravitational lenses, galaxies, and nebulae. The volunteers, along with an algorithm based on artificial intelligence (AI), collectively identified 1,701 asteroid trails. Roughly one-third of the trails came from known asteroids, the remaining 1,031 trails came from unidentified objects. Of these unidentified objects, roughly 400 were below two-thirds of a mile (one kilometer) in size.

Research like this not only helps us better understand our neighborhood, but also helps us locate its dangers. By finding and identifying unknown asteroids in our solar system, scientist can determine which ones could pose a potential impact hazard to Earth, aiding NASA's planetary defense efforts.

Mapping Star Clusters in Andromeda

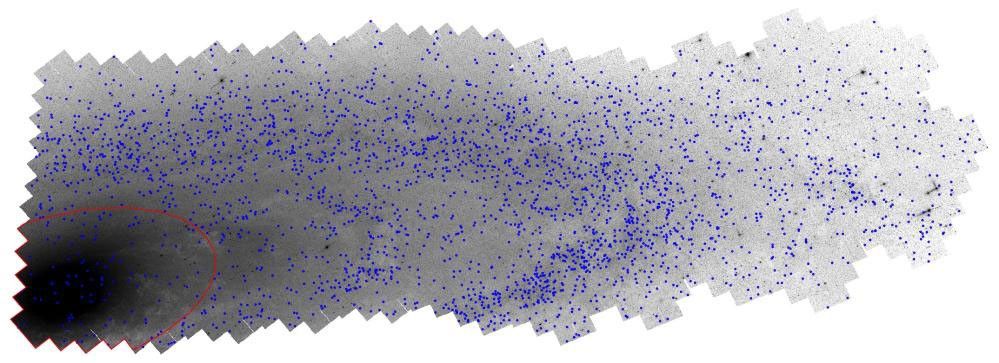

Hubble citizen scientists also helped researchers study our neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy. The Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury (PHAT) resolved more than 100 million stars, as well as dust clouds and numerous star clusters, in wavelengths from ultraviolet to near infrared. Hubble’s multicolor data provided the basis for investigating details of star formation across the galaxy, while simultaneously creating an extensive catalog of interesting features, especially star clusters, in the galaxy.

Initial data from the project more than doubled the number of known star clusters in the areas of the galaxy that Hubble observed. Because the Andromeda Galaxy is so large and relatively close to us, the entirety of the galaxy does not fit into Hubble’s field of view. Hubble’s instruments imaged overlapping sections of the galaxy that image processors pieced together to form a mosaic.

Researchers launched phase one of this citizen science project in 2012 from December 5-21 and phase two from October 22-30, 2013. Roughly 30,000 volunteers contributed 1.82 million image classifications that identified 2,753 star clusters and 2,270 background galaxies.

Local Group Cluster Search

With the success of the Andromeda Project, researchers expanded the program by looking for star clusters in three additional galaxies in our local neighborhood. The resulting Local Group Cluster Search project included the Andromeda Galaxy, the Triangulum Galaxy, the Large Magellanic Cloud, and the Small Magellanic Cloud.

In January of 2019, volunteers began searching a 665-million-pixel mosaic image of the Triangulum Galaxy taken with the Wide Field Channel on Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys. The image included 54 discrete fields of view that spanned 19,400 light-years and resolved nearly 25 million individual stars. By the end of February, roughly 2,800 volunteers had contributed to the search of 4,428 Hubble images, finding 1,214 star clusters.

The Triangulum Galaxy is teeming with newly forming stars. This contrasts nicely with the Andromeda Galaxy that is in a quiet star-formation period. The Triangulum Galaxy has nearly 10 times the spatial density of star formation that Andromeda has, which allows astronomers to learn more about how new stars form.

In March of 2019, researchers launched star cluster searches of the Small, then Large, Magellanic Clouds. That iteration of the project used ground-based data from SMASH (Survey of the Magellanic Stellar History) taken by the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the Blanco 4-m telescope at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.

In October 2025, the Local Group project continued their cluster search with the Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Southern Treasury (PHAST) that extended Hubble’s PHAT mosaic by adding roughly 100 million additional stars.

STAR DATE: M83

One of Hubble’s proficiencies is its resolving power. The space telescope can distinguish astronomical objects with an angular diameter of a mere 0.05 of an arcsecond – that's like seeing the width of a dime from 86 miles (138 km) away. Hubble's resolution is about 10 times better than the best resolution typically attained by larger, ground-based telescopes. High resolution enables Hubble to image objects like individual stars at the core of densely packed globular star clusters, dust disks around stars, or the glowing nuclei of extremely distant galaxies.

Because stars form in groups or clusters and may be surrounded by clouds of gas and dust, depending on their age, Hubble’s resolving power is particularly useful for examining them. By studying individual stars, astronomers can determine their ages, and since they form in groups, they generally have relatively the same age. Understanding a star’s age and knowing its brightness (from which researchers can determine the star’s mass or physical size) tells us how star clusters formed and how that process varies across a given galaxy or between different galaxies.

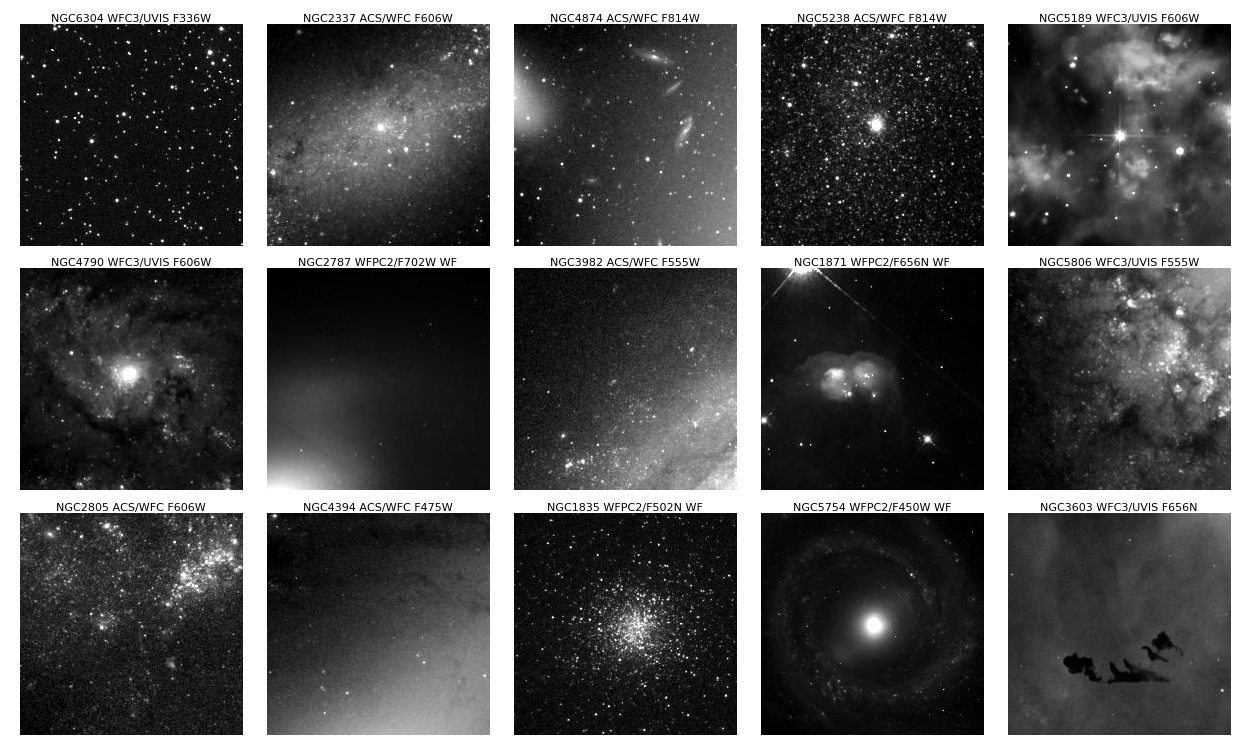

The STAR DATE: M83 project used Hubble data to measure the ages of roughly 3,000 star clusters in the spiral galaxy Messier 83 (M83), also called The Southern Pinwheel. Before the project began, researchers cataloged the clusters by measuring their light at different wavelengths, allowing them to assign ages to the clusters. They ran algorithms that use the distribution, brightness, and color of a cluster's individual stars to compute a composite color for the entire cluster. The astronomers compared the color of the whole cluster to its brightness in different filters (ultraviolet, blue, yellow, and red). Blue clusters are young, a few million years old. They are generally large, massive, hot, young stars that primarily emit blue light and often dominate a cluster's brightness. Red or sometimes yellowish colored clusters tend to be old (more than one billion years), and clusters with intermediate colors (green, white) tend to have intermediate ages.

The research team called upon citizen scientists to help them verify whether the automated ages assigned by the algorithm were accurate. Volunteers used the presence or absence of pink hydrogen emission, the sharpness of individual stars, and the color of clusters to estimate their ages. They also measured the sizes of star clusters and any associated emission nebulae, and identified background galaxies, supernova remnants, and foreground stars in the Hubble image.

Most of the star cluster ages assigned by citizen scientists roughly matched the ages assigned by the algorithm. Where the algorithm and citizen scientist assigned ages didn’t agree, the citizen scientists’ ages were better. The work of these volunteers corrected about two to three percent of the wrong age estimates generated by the algorithm.

Finding Similarities

There is no easy way to search for objects that have similar visual characteristics. Searchers can use an image’s metadata (the object’s position; the camera, instruments, and filters used in the observation; the exposure date and time; the object type; etc.), but none of these search parameters have the capability of finding complex structures. Image search algorithms can help, but are they accurate?

Researchers designed the Hubble Image Similarity Project as a way to test the accuracy of image search algorithms built on computer vision methods. The project asked volunteers to find similarities between subregions of Hubble images based on their form, texture, and other details, some difficult to describe in words (e.g., dusty, dark, bands with sharp edges). The volunteers made nearly 850,000 comparison measurements on 2,089 images. Researchers used these comparisons to create an image similarity matrix that describes how alike the images are. They represented this similarity with a figurative “distance” between images, where very similar images had the smallest distance apart. This matrix resulted in the discovery that the collective accuracy of the project's volunteers matched the accuracy of the trained eye. The work of volunteers even reflected subtle differences between images.

The resulting large database will help researchers assess the accuracy of image-search algorithms that are based on computer vision methods.

Although Hubble’s vast and growing archive of data is ripe for algorithms and artificial intelligence to analyze in search of new discoveries, these Hubble citizen science projects illustrate the need for a human touch.

Participate

NASA Citizen Science

Explore NASA citizen science projects and join researchers on their journey of discovery.

NASA needs your help! You can collaborate with professional scientists, participate in cutting-edge research, and make real discoveries. You don't need a science degree, just a passion for understanding the natural world. Learn more and read the latest news about NASA-funded citizen science projects, new discoveries, and opportunities to get involved.

Learn More about NASA Citizen Science