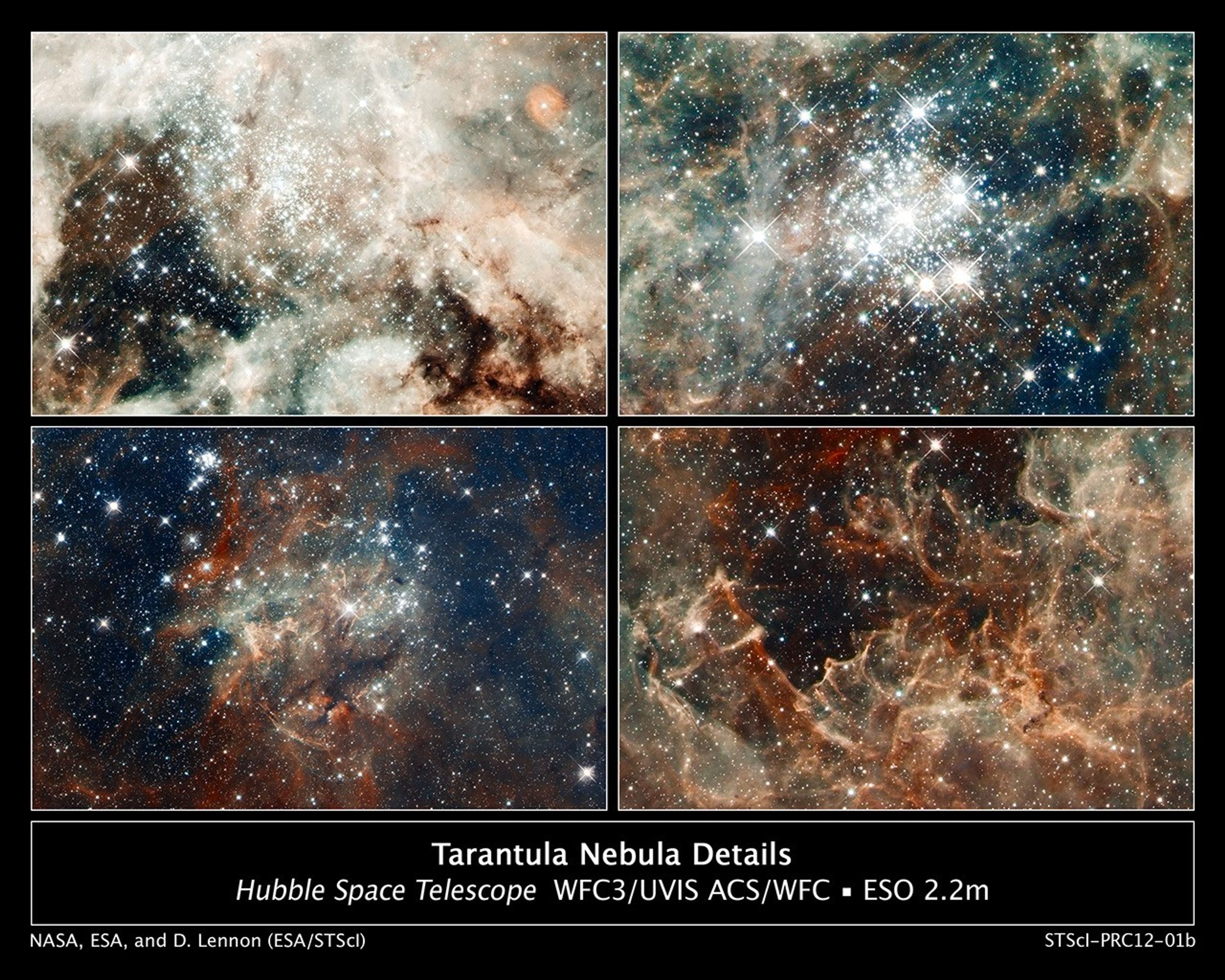

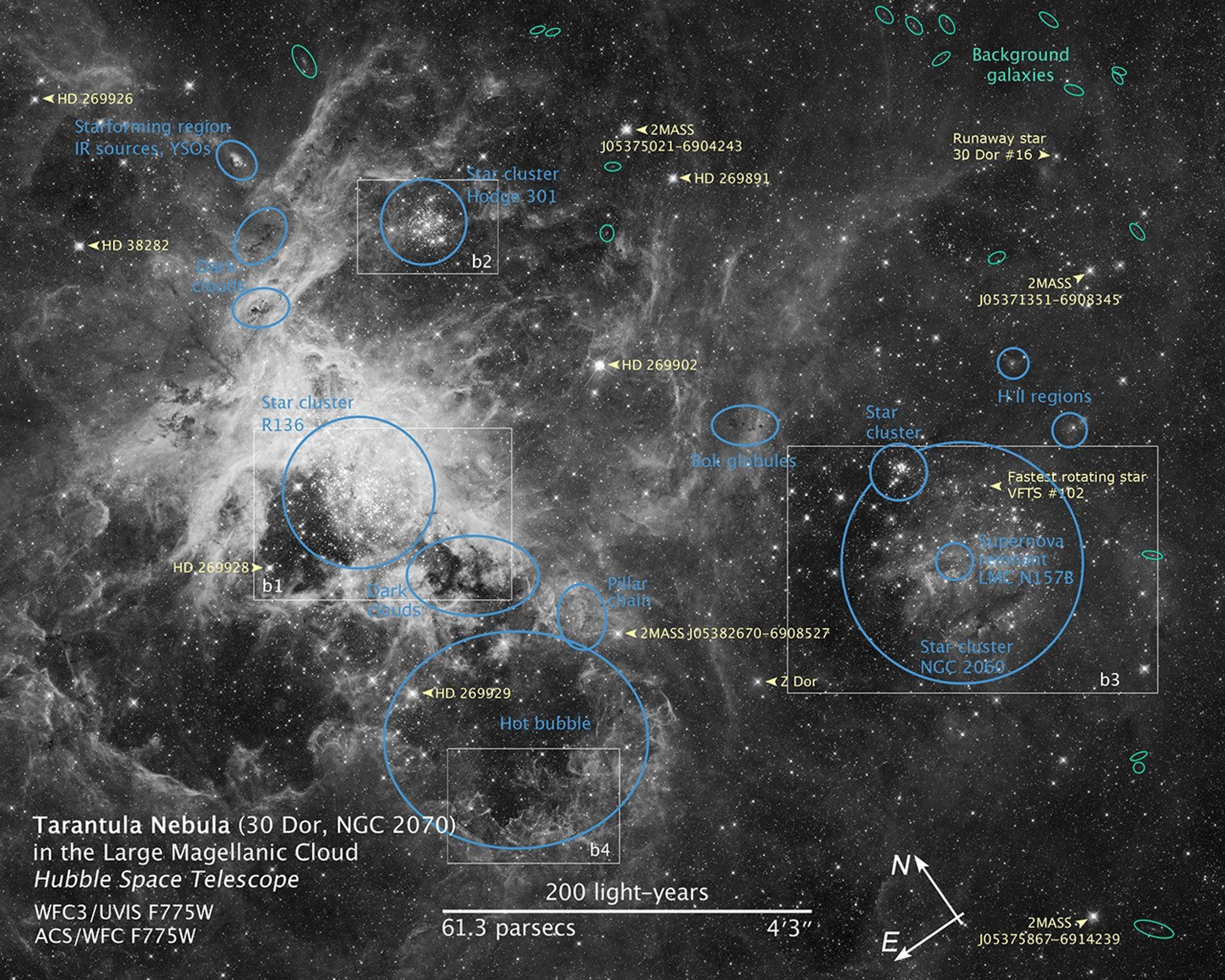

Several million young stars are vying for attention in a new NASA Hubble Space Telescope image of a raucous stellar breeding ground in 30 Doradus, a star-forming complex located in the heart of the Tarantula nebula.

The new image comprises one of the largest mosaics ever assembled from Hubble photos and includes observations taken by Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 and Advanced Camera for Surveys. NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore released the image today in celebration of Hubble's 22nd anniversary.

"Hubble is the world's premiere science instrument for making celestial observations, which allow us to unravel the mysteries of the universe," said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington and three-time Hubble repair astronaut. "In recognition of Hubble's 22nd birthday, the new image of the 30 Doradus region, the birth place for new stars, is more than a fitting anniversary image."

30 Doradus is the brightest star-forming region in our galactic neighborhood and home to the most massive stars ever seen. The nebula is 170,000 light-years away in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. No known star-forming region in our galaxy is as large or as prolific as 30 Doradus.

Collectively, the stars in the image are millions of times more massive than our sun. The image is roughly 650 light-years across and contains some rambunctious stars, including one of the fastest rotating stars and the highest velocity stars ever observed by astronomers.

The nebula is close enough to Earth that Hubble can resolve individual stars, giving astronomers important information about the stars' birth and evolution. Many small galaxies have more spectacular starbursts, but the Large Magellanic Cloud's 30 Doradus is one of the only star-forming regions that astronomers can study in detail. The star-birthing frenzy in 30 Doradus may be fueled partly by its close proximity to its companion galaxy, the Small Magellanic Cloud.

The image reveals the stages of star birth, from embryonic stars a few thousand years old and still wrapped in cocoons of dark gas, to behemoths that die young in supernova explosions. 30 Doradus churns out stars at a furious pace over millions of years. Hubble shows star clusters of various ages, from about 2 million to 25 million years old.

The region's sparkling centerpiece is a giant, young star cluster named NGC 2070, only 2 million to 3 million years old. Its stellar inhabitants number roughly 500,000. The cluster is a hotbed for young, massive stars. Its dense core, known as R136, is packed with some of the heftiest stars found in the nearby universe, weighing more than 100 times the mass of our sun.

The massive stars are carving deep cavities in the surrounding material by unleashing a torrent of ultraviolet light, which is winnowing away the enveloping hydrogen gas cloud in which the stars were born. The image reveals a fantastic landscape of pillars, ridges and valleys. Besides sculpting the gaseous terrain, the brilliant stars may be triggering a successive generation of offspring. When the ultraviolet radiation hits dense walls of gas, it creates shocks, which may generate a new wave of star birth.

The image was made using 30 separate fields, 15 from each camera. Both cameras made these observations simultaneously in October 2011. The colors in the image represent the hot gas that dominates regions of the image. Red signifies hydrogen gas and blue represents oxygen.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., manages the telescope. STScI conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., in Washington.

Background Information: Hubble's Greatest Scientific Achievements

The Hubble Space Telescope is one of the most powerful and prolific science instruments ever made, earning a place as one of the technical wonders of the modern world. From its lofty perch 350 miles above Earth, Hubble sees farther and sharper than any previous telescope, producing breathtaking images that have astounded astronomers and the public. Its discoveries have revolutionized nearly all areas of astronomy, from planetary science to cosmology.

A series of heroic astronaut servicing missions to Hubble has made it the longest-operating space observatory ever built. Thanks to routine maintenance and upgrades Hubble is 100 times more powerful than when it was launched. In addition to its scientific importance, Hubble brings cosmic wonders into millions of homes and schools worldwide, allowing the public to be co-explorers with this wondrous observatory.

Here are some of Hubble's top science discoveries.

An Accelerating Universe

By using bursts of light from faraway exploding stars to measure the expansion of space, Hubble provided important supporting evidence for the existence of a mysterious "dark energy" that pervades our universe. Dark energy exerts a repulsive force that works against gravity and causes the universe to expand at an ever-faster rate.

But dark energy wasn't always in the driver's seat. By studying distant supernovas, Hubble traced dark energy all the way back to 9 billion years ago, when the universe was less than half its present size. During that epoch, dark energy was arm-wrestling with gravity for control of the cosmos. Dark energy finally won the struggle with gravity about 5 billion years ago.

By knowing more about how dark energy behaves over time, astronomers hope to gain a better understanding of what it is. Astronomers still do not know what dark energy is, even though it appears to comprise about 70 percent of the universe's energy.

How Old Is the Universe?

Some people hate to reveal their age, and the universe, it seems, is no different. Before Hubble was launched, astronomers had been trying for many years to pin down the universe's age. The method relied on determining the expansion rate of the universe, a value called the Hubble constant. Their values for the Hubble constant were highly uncertain. Consequently, their calculations for the universe's age ranged from 10 to 20 billion years.

One of Hubble's key duties was to help astronomers determine a precise age for the universe. The telescope's keen vision helped astronomers accomplish that goal by measuring the brightness of dozens of pulsating stars called Cepheid variables, which are a thousand times brighter than the Sun. By knowing their brightness, astronomers then calculated the stars' distance from Earth. From this study and other related analyses, astronomers determined the Hubble constant and the universe's age to an accuracy of about 3.3 percent. By their calculations, the universe is about 13.75 billion years old.

Galaxies from the Ground Up

Hubble's surveys of deep space showed that the universe was different long ago, providing evidence that galaxies grew over time through mergers with other galaxies to become the giant galaxies we see today.

The telescope snapped images of galaxies in the faraway universe in a series of unique observations, including the Hubble Deep Fields and the Hubble Ultra Deep Field. In the most recent foray into the universe's farthest regions, Hubble's newly installed Wide Field Camera 3 produced the deepest photographs of the universe in visible and near-infrared light and uncovered a galaxy that existed when the universe was only 450 million years old.

All of the "Deep Field" observations have shed light on galaxy evolution. The galaxies spied by Hubble are smaller and more irregularly shaped than today's grand spiral and elliptical galaxies, reinforcing the idea that large galaxies built up over time as smaller galaxies collided and merged.

By studying galaxies at different epochs, astronomers can see how galaxies change over time. The process is analogous to a very large scrapbook of pictures documenting the lives of children from infancy to adulthood.

Hubble also probed the dense, central regions of galaxies and provided decisive evidence that supermassive black holes reside in the centers of almost all large galaxies. Giant black holes are compact "monsters" weighing millions to billions the mass of our Sun. Their gravity is so strong that they gobble up any material that ventures near them.

These elusive "eating machines" cannot be observed directly, because nothing, not even light, escapes their clutches. The telescope provided indirect, yet compelling, evidence of their existence. Hubble helped astronomers determine the masses of several black holes by measuring the velocities of material whirling around them.

Hubble's census of more than 30 galaxies showed an intimate relationship between galaxies and their resident black holes. The survey revealed that the black hole's mass is dependent on the weight of its host galaxy's central bulge of stars. The bigger the bulge of stars, the more massive the black hole. This close relationship means that black holes may have evolved with their host galaxies, feasting on a measured diet of gas and stars residing in the hearts of those galaxies.

Worlds Beyond Our Sun

At the time of Hubble's launch in 1990, astronomers had not found a single planet outside our solar system. Now there are about 1,500 known extrasolar planets, most of them discovered by the Kepler observatory and by ground-based telescopes. But Hubble has made some unique contributions to the planet hunt.

The telescope demonstrated that our Milky Way galaxy is probably brimming with billions of planets. Peering into the crowded bulge of our Milky Way galaxy, Hubble observed 180,000 stars and nabbed 16 potential alien worlds orbiting a variety of stars. Five of the candidates represent a new type of extreme planet. Dubbed Ultra-Short-Period Planets, these objects whirl around their stars in less than an Earth day. Astronomers made the discoveries by measuring the slight dimming of a star as a planet passed in front of it, an event called a transit.

The transit method was used again to make the first measurements of the atmospheric makeup of at least two extrasolar planets. The Hubble observations showed that the atmosphere of a known extrasolar planet contains sodium, oxygen, carbon, and hydrogen. A similar study of another alien world revealed probable signs of carbon dioxide, methane, and water. These two Jupiter-sized planets are too hot for life. But the Hubble observations demonstrate that the basic chemistry for life can be measured on planets orbiting other stars.

Finally, Hubble made the first visible-light image of an extrasolar planet circling the nearby, bright southern star Fomalhaut, located 25 light-years away in the constellation Piscis Australis. An immense debris disk about 21.5 billion miles across surrounds the star. The planet is orbiting 1.8 billion miles inside the disk's sharp inner edge, about 10 times the distance of Saturn from the Sun.

Shining a Light on Dark Matter

Astronomers used Hubble to make the first three-dimensional map of dark matter, an invisible form of matter that makes up most of the universe's mass and forms its underlying structure. Dark matter's gravity allows normal matter in the form of gas and dust to collect and build up into stars and galaxies.

Although astronomers cannot see dark matter, they can detect its influence in galaxy clusters by observing how its gravity bends and distorts the light of more distant background galaxies, a phenomenon called gravitational lensing.

Using Hubble's sharp view, astronomers used the gravitational lensing technique to construct the three-dimensional map by studying the warped images of half a million faraway galaxies. The new map provides the best evidence to date that normal matter, largely in the form of galaxies, accumulates along the densest concentrations of dark matter. The map stretches halfway back to the beginning of the universe and reveals a loose network of dark-matter filaments.

Astronomers also used Hubble to observe dark matter's distribution in the titanic collisions of clusters of galaxies. In one case, a combination of observations by Hubble and NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory suggests that dark matter and normal matter in the form of hot gas were pulled apart by the smashup between two groupings of galaxies, known as the Bullet Cluster.

In another Hubble gravitational lensing study of another galaxy cluster, astronomers discovered a ghostly ring of dark matter that formed long ago during a clash between two groups of massive galaxies. Astronomers have long suspected that such clusters would fly apart if they relied only on the gravity from their visible stars. The ring is a ripple of dark matter that was pulled apart from normal matter during the collision.

Computer simulations of galaxy cluster collisions show that when two clusters smash together, the dark matter flows through the center of the combined cluster. As it moves outward from the core, it begins to slow down under the pull of gravity and pile up.

Background Information: Hubble Trivia 2012

Launched in 1990, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has made slightly more than 1 million observations of 34,500 celestial objects.

In its 22-year lifetime the telescope has made more than 120,000 trips around our planet.

Hubble has racked up plenty of frequent-flier miles, nearly 3 billion, which is roughly Neptune's average distance from the Sun.

Over its more than two decades in space, Hubble has produced more than 60 terabytes of data.

Astronomers using Hubble data have published more than 10,000 scientific papers, making it one of the most productive scientific instruments ever built.