Dual Anonymous Peer Review (DAPR)

“Guidelines for Proposers to ROSES Dual-Anonymous Peer Review Programs” Document (PDF)

“Dual-Anonymous Peer Review Guidelines for Proposers to Astrophysics General Investigator/General Observer ROSES Programs” Document (PDF)

The Problem: Cognitive Bias and the Peer Review Process

Cognitive biases are psychological filters that the human brain has developed to help us rapidly identify and organize key information in the flood of data our senses are constantly feeding to our brains. As such, cognitive biases are neither inherently good nor bad--everyone possesses cognitive biases of one sort or another and those filters are very valuable to us at times when we must rapidly assess a situation and make split-second decisions. However, cognitive biases have a detrimental effect on rational decision-making processes like proposal reviews by making our thought processes less rational and more subjective. More information about cognitive bias can be found in the seminal paper on the topic by Tversky and Kahneman (Science, 27 Sept. 1974, Vol. 185, No. 4157, pp. 1124-1131).

Ideally, we would like the evaluation of proposals to be an objective process that is independent of the “filters” through which each individual views the world. Since cognitive biases are manifested as short-cuts in our thought processes, we can partially mitigate their impact by making those thought processes as explicit as possible. At NASA, we have traditionally addressed this need by providing reviewers with a clearly defined set of evaluation criteria to follow. These criteria include: (1) the intrinsic scientific or technical merit of the proposed work; (2) the relevance of the proposed work to NASA; and (3) the suitability of the proposed costs. Reviewers are instructed to frame their discussion and evaluation of proposals in terms of those evaluation criteria and to present clear reasoning that is tied to those criteria in their written findings.

While NASA’s already established practices reinforce the objectivity of the proposal review process, they are not sufficient to consistently and effectively disrupt cognitive bias. Accomplishing that important goal requires actual structural changes in the way proposals are written and reviewed.

A Solution: The Dual-Anonymous Peer Review

NASA’s Science Mission Directorate (SMD) is strongly committed to ensuring that the review of proposals is performed in an objective and fair manner. To this end, SMD has adopted a dual-anonymous approach for the review of proposals to most ROSES programs. Under this system, not only do proposers not know who the reviewers are, the reviewers are not told who the proposers are, until after the evaluation and rating of all proposals is complete.

The objective of the dual-anonymous peer review (DAPR) is to minimize the impact of cognitive bias in the peer review process by eliminating “the team” as a topic of discussion during the scientific evaluation of a proposal. However, DAPR does not achieve this goal by making it somehow impossible for reviewers to figure out who the authors of a proposal might be (an unrealistic goal for the review of scientific proposals). Indeed, the effectiveness of DAPR doesn’t derive from maintaining absolute, iron-clad anonymity. Rather, the effectiveness of DAPR derives from the way proposals are written; a way that decouples the proposed investigation from the people and institutions who are conducting that investigation. In changing the way information is presented in a proposal, DAPR naturally creates a shift in the tenor of discussions, drawing the focus away from the perceived characteristics of the people and institutions involved and placing it squarely on the intrinsic scientific and technical merit, NASA relevance, and cost of the proposed investigation.

The Mechanism of the DAPR Review

Under DAPR, the standard review of proposals is split into two parts: a scientific evaluation followed by a validation of the proposer’s expertise and resources. To this end, proposers are instructed to prepare and submit both an anonymized proposal document and separate, companion “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized”—or simply “E&R”—document.

Although the overall merit of each proposal is assessed based only on the information provided in the anonymized proposal document, validation of the qualifications, track record, and access to unique facilities is still an important component of the process. Ultimately, the same factors that have always been considered in the evaluation of proposals to NASA are still considered under DAPR. The difference is, under DAPR those factors are considered in two sequential steps rather than all at once.

The two-stage DAPR review process is summarized in the figure below. During the first stage of the process, reviewers have access only to the anonymized proposal documents while conducting their individual evaluations of the proposals in advance of the panel meeting, and throughout the discussion, evaluation, and rating of the proposals at the panel meeting.

After the written evaluations and ratings of all proposals assigned to a panel have been finalized, the “E&R” documents are distributed for the highest rated proposals—that is, only those proposals that are likely to be considered for selection.

In the second stage of the process, panels are given an opportunity to review the information contained in the E&R document and validate the qualifications of the team and the availability of any supporting resources needed to execute the proposed investigation. More details about the review of DAPR proposals is provided in the section titled, “Evaluation of Proposals in Dual-Anonymous Peer Review” below.

Illustration of the 2-Stage Review Process under DAPR

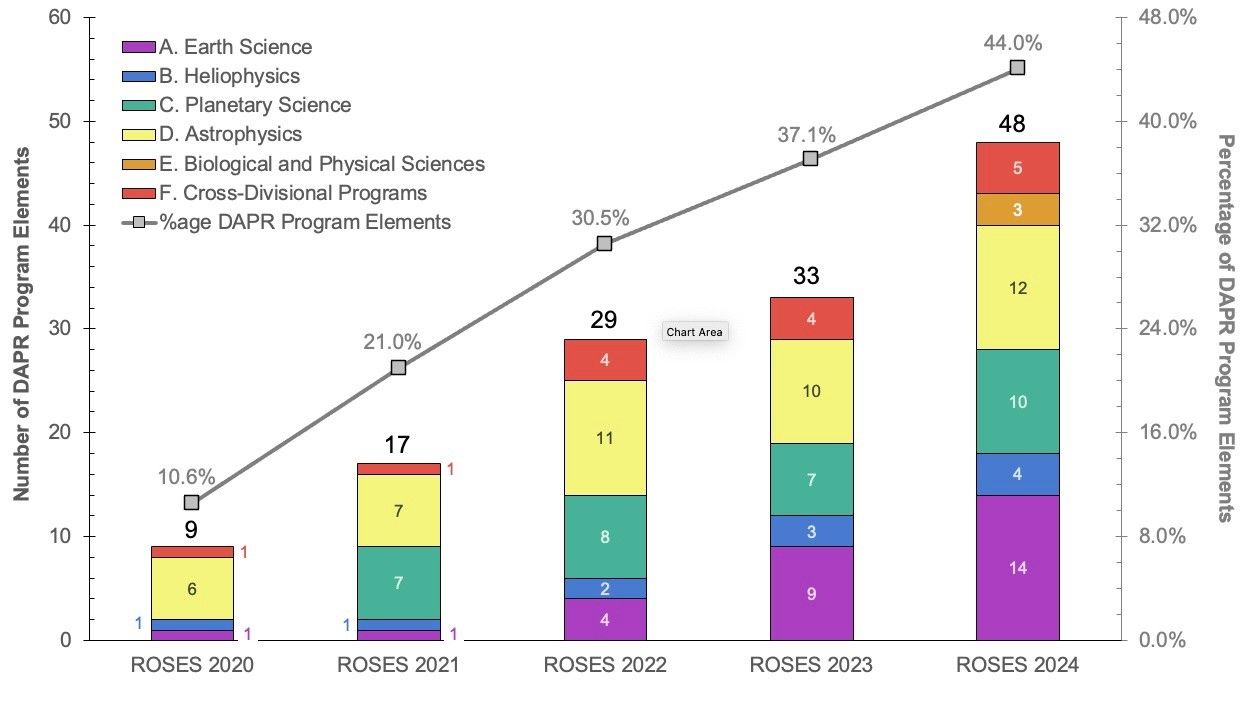

The Implementation of the DAPR Process for ROSES Programs

SMD’s implementation of DAPR began under ROSES 2020 with a pilot study involving 4 ROSES programs—one each from Earth Science (Appendix A), Heliophysics (Appendix B), Planetary Science (Appendix C), and Astrophysics (Appendix D). At that time, the Astrophysics Division also converted all its Mission General Observer programs in ROSES to DAPR, giving a total of 9 DAPR program elements in that first year—about 10% of all the ROSES program elements in 2020. As illustrated in the figure below, the number of ROSES program elements running under DAPR has grown steadily each year since, with DAPR programs making up about 20% of ROSES-2021 programs, 30% of ROSES-2022 programs, 37% of ROSES-2023 programs, and 44% of ROSES-2024 programs. Under ROSES-2025, DAPR will become the default approach for the review of proposals, so the numbers in this plot will grow considerably in coming years.

The Growth of DAPR in SMD

The Impact of DAPR

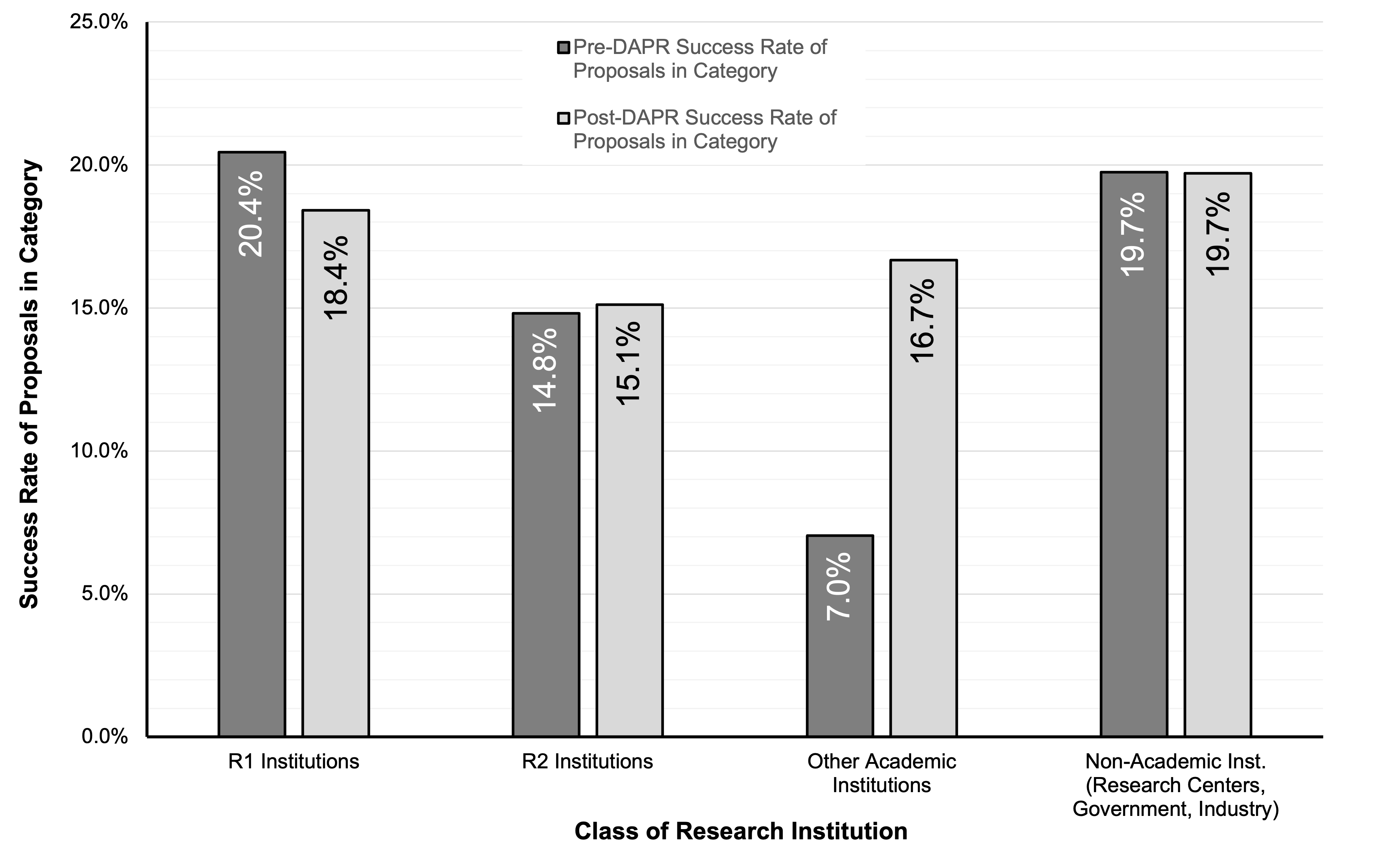

The impact of negating cognitive bias can be illustrated by comparing the outcomes of ROSES proposal reviews before and after the implementation of DAPR. For example, the figure shown below compares the success rates of proposals from different classes of academic institutions and non-academic research entities before and after the implementation of the DAPR. The classifications of the academic institutions follow the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, with R1 and R2 denoting doctorate-granting institutions having the highest and second highest levels of research activity, respectively. The non-academic institution category includes entities such as the NASA field centers, other federal laboratories, and industry. The “Other Academic institutions” includes academic institutions that are typically not well represented in the NASA Research and Technology Development enterprise (e.g. smaller universities, primarily undergraduate colleges and universities, community colleges, etc.).

The data for this plot were drawn from three SMD programs that are solicited under ROSES—the Astrophysics Data Analysis Program (ADAP), the Astrophysics Theory Program (ATP), and the Exoplanets Research Program (XRP). It encompasses more than 20 proposal cycles with around 4500 proposals prior to the implementation of DAPR, and 6 proposal cycles with around 1000 proposals since these programs adopted the DAPR approach.

In the figure, the dark bars on the left reflect the average success rate of proposals prior to DAPR, while the lighter bars on the right reflect the average success rate of proposals since the implementation of DAPR. Success rate is defined as the number of proposals from a given class that were selected for funding divided by the total number of proposals submitted by institutions in that class.

The plot shows that the success rates of proposals from R1 institutions, R2 institutions, and non-academic institutions were only minimally affected by the introduction of DAPR. The situation is dramatically different for proposals in the “Other Academic institutions” category for which the average success rate of proposals more than doubled after the introduction of DAPR. While the absolute number of proposals received from “Other Academic institutions” is much smaller than that from other institutional classes, a change of this magnitude is not simply an artifact of small number statistics.

An Example of the Impact of DAPR

Community Feedback about DAPR

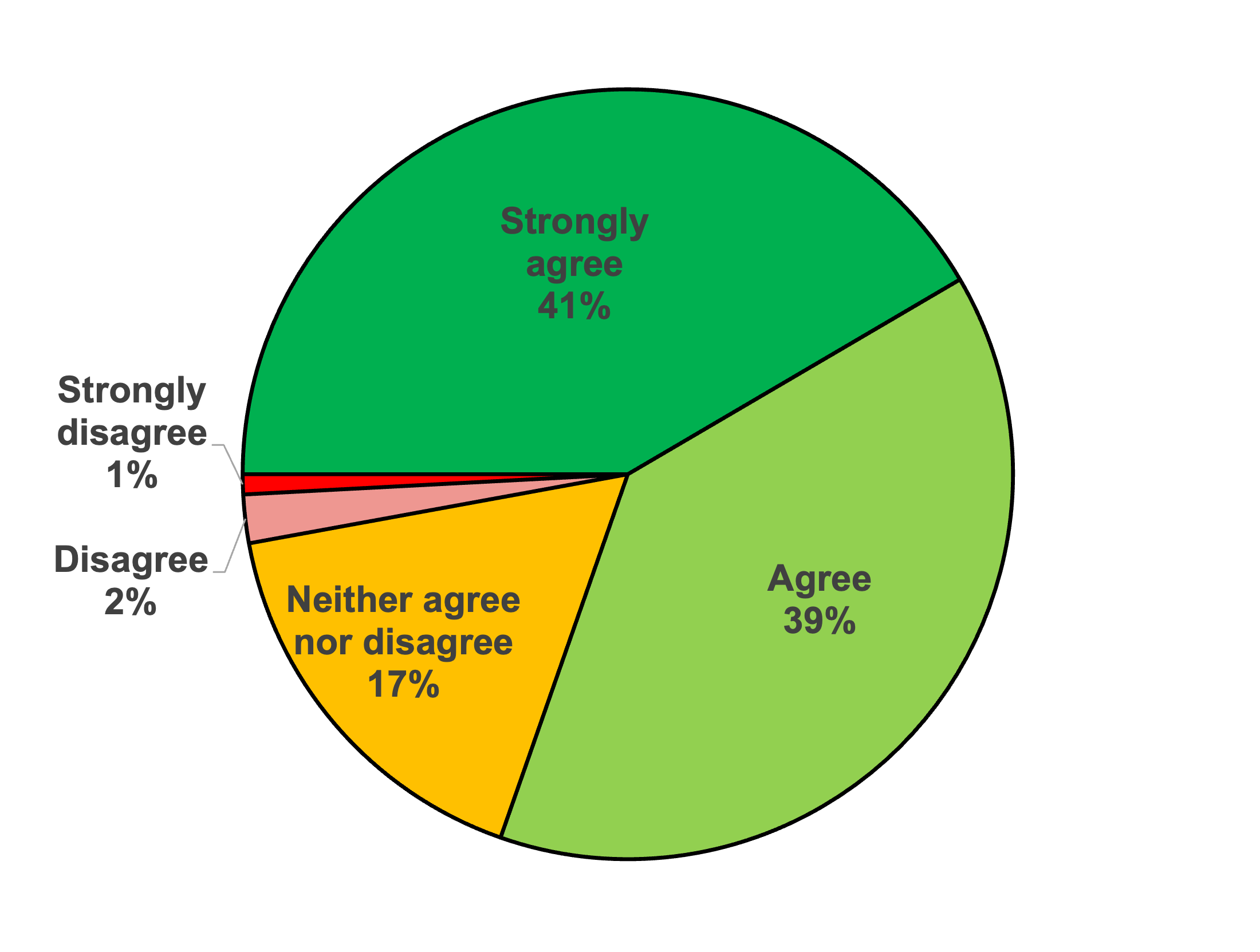

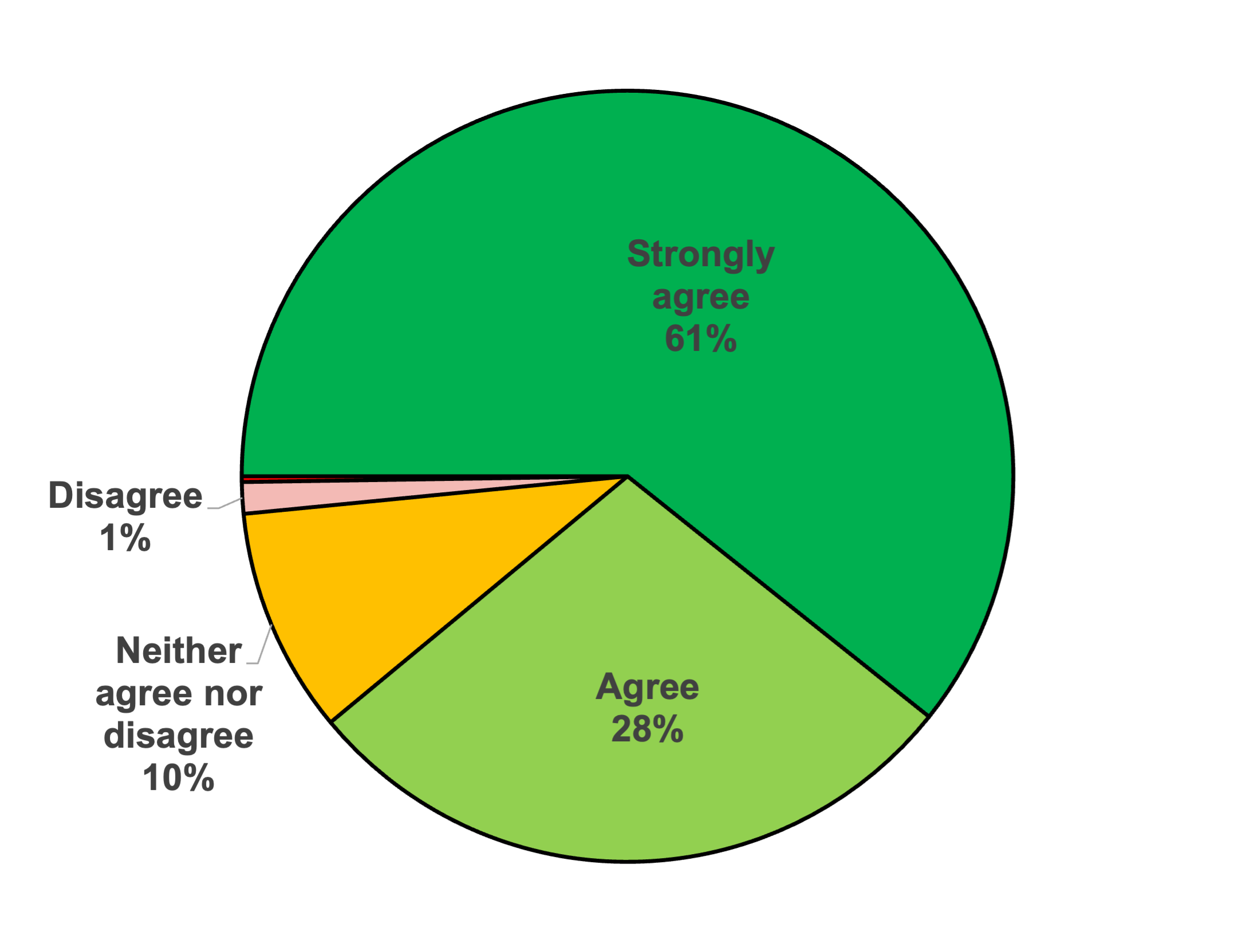

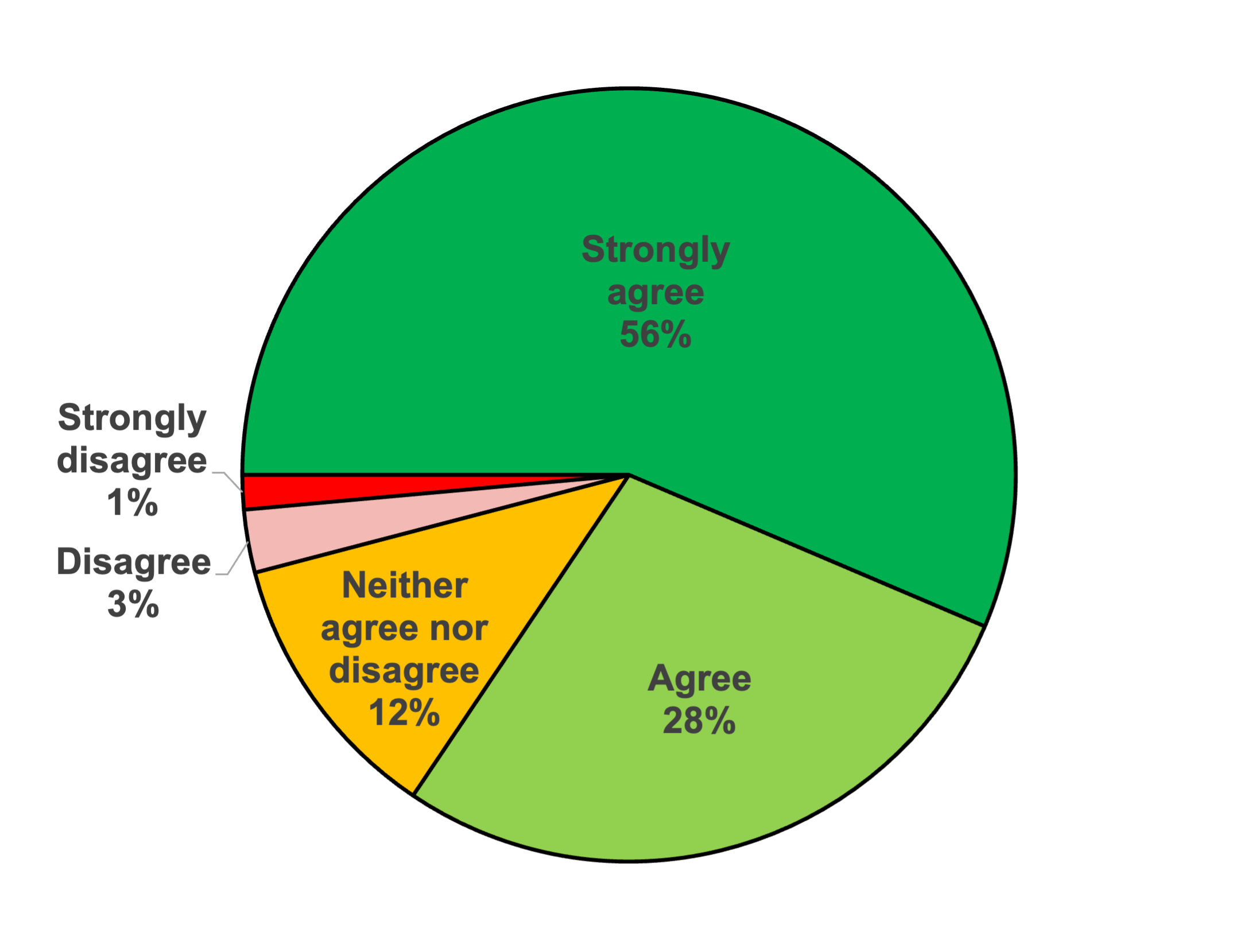

It is also worthwhile to consider how the implementation of DAPR has been received by SMD’s stakeholder communities. To that end, we developed a short questionnaire that we use to solicit feedback from reviewers who have participated in one of SMD’s DAPR reviews. In that questionnaire, respondents are asked to rate their level of agreement with a series of statements pertaining to the DAPR process using a 5-tier scale: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree.

The pie charts shown below illustrate the feedback we have received over the 5-year period since the initial DAPR pilot for three key statements. They reflect the feedback responses from 835 respondents representing 26 different ROSES programs from across SMD. The responses described in detail below indicate that DAPR is not only effective in placing the focus of the peer review squarely on the scientific/technical aspects of a proposal, but also that its adoption by NASA is overwhelmingly supported by the reviewers who have participated in the process.

In response to the statement, “The DAPR procedure improved the overall quality of the peer review.”, 80% of respondents indicated that they either agree or strongly agree.

| DAPR Improves the Quality of the Peer Review Pie Chart illustrating the responses to the statement: “The DAPR procedure improved the overall quality of the peer review.” Figure based on 825 responses representing 26 different ROSES program elements. Data collected via feedback form sent to individuals who served on a ROSES DAPR review panel over the years 2020-2024. |

In response to the statement, “The DAPR procedure led to panel discussions being focused on the science rather than on the identities of the team members.”, 89% of respondents indicated that they either agree or strongly agree.

| DAPR Reviews Focus on the Science, Not the People Pie Chart illustrating the responses to the statement: “The DAPR procedure led to panel discussions being focused on the science rather than on the identities of the team members.” Figure based on 825 responses representing 26 different ROSES program elements. Data collected via feedback form sent to individuals who served on a ROSES DAPR review panel between 2020 and 2024. |

And finally, in response to the statement, “The Dual-Anonymous Peer Review process should be implemented in the future for the program I reviewed this year.”, 84% of respondents indicated that they either agree or strongly agree.

| NASA Should Continue to Implement DAPR Pie Chart illustrating the responses to the statement: “The Dual-Anonymous Peer Review process should be implemented in the future for the program I reviewed this year.” Figure based on 825 responses representing 26 different ROSES program elements. Data collected via feedback form sent to individuals who served on a ROSES DAPR review panel between 2020 and 2024. |

Overall, this feedback indicates that the reviewers—the people actively participating in the execution of the DAPR process—overwhelmingly feel that DAPR has a positive impact on the overall review process, that it produces the shift in the tenor of discussions that it is intended to, and that it should continue to be implemented by SMD.

Sources of DAPR Information for Prospective Proposers

Any ROSES programs that will be using the DAPR process will say so explicitly in the program element text. In addition, the NSPIRES solicitation page of any program element using DAPR will provide a link to the informational, “Guidelines for Proposers to ROSES Dual-Anonymous Peer Review Programs” (or simply the Guidelines for DAPR Proposers document) under the heading “Other documents”. For proposers to the Astrophysics General Investigator/General Observer programs that are solicited under ROSES, there is a version of the instructional document entitled “Dual-Anonymous Peer Review Guidelines for Proposers to Astrophysics General Investigator/General Observer ROSES Programs” that has been tailored specifically to the specialized requirements of those programs.

The text of each DAPR program element contains a section that summarizes the key requirements for the preparation of anonymized proposals, as well as an overview of the review process (or points prospective proposers to the location where such information can be found). This DAPR section will also describe any program-specific DAPR requirements of the program. Proposers should familiarize themselves with any such program-specific requirements and ensure that their proposals are fully compliant with the call. When in doubt, the information provided in the text of the program element supersedes that found in other, more general sources of information regarding DAPR requirements.

Submission of Proposals

Proposers to ROSES DAPR programs should fill in all required information on the NSPIRES cover page (e.g., team members, institutions) as they would with any ROSES program. Anonymization of the information provided in the NSPIRES cover pages is not necessary because the fields containing identifying information are automatically hidden in the peer review copy of the proposal. The one exception is for the Proposal Summary, which is included in the review copy of the proposal and must be anonymized, omitting names of the team members or their institutions as well as any other individually-identifying information.

For programs that follow the 2-Step proposal process, anonymization of the Step-1 proposals may or may not be required. Proposers should refer to the guidance provided in their specific program element of interest to determine whether anonymization is required for their Step-1 proposals. Regardless of the approach followed for the Step-1 proposals, Step-2 (full) proposals must be anonymized according to the guidelines provided in the program element and in the Guidelines for DAPR Proposers document.

In general, under DAPR, proposed investigations are presented in two parts: (1) an anonymized proposal document; and (2) a separate “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized” document (or simply the “E&R document”). These two documents are uploaded separately in the NSPIRES system along with the standard “Total Budget” document, and the NASA-provided High-End Computing (HEC) request form (if applicable) when the proposal is submitted. The anonymized proposal document contains all the information necessary for reviewers to assess the intrinsic scientific and technical merit of the proposed investigation, it’s relevance to NASA, and the appropriateness of the proposed work effort and other costs. The E&R document contains the information necessary for a reviewer to validate that the qualifications of the proposing team and the resources to which they have access are suitable for conducting the proposed investigation. A summary of the contents of these two documents and guidance for their preparation are provided below.

The Anonymized Proposal Document

First and foremost, proposers should keep in mind that the specific requirements for anonymized proposals to different ROSES program may vary. Proposers should always review the DAPR section in their program element of interest to make sure that they are aware of any program-specific DAPR requirements of that program.

In general, the anonymized proposal document includes the following components of the standard ROSES proposal:

- Scientific/Technical/Management (S/T/M) section;

- Reference section;

- Open Science Data Management Plan (OSDMP);

- Table of personnel and Work Effort;

- Redacted Budget and Budget Justification;

The content of any sections of the proposal that are included in the anonymized proposal document must be anonymized in accordance with the instructions summarized below and described in greater detail in the Guidelines for DAPR Proposers document. Proposals that contain errors in anonymization may be penalized during the review by the assessment of one or more weaknesses dependent on the impact and extent of those errors. Proposals with DAPR errors that are so numerous and/or egregious that the program officer concludes the proposers did not make a good faith effort to follow the guidelines for anonymization may be declared non-compliant and declined without review.

Guidelines for Proper Anonymization

Proposers are required to present the contents of the main proposal document in an anonymized format, i.e., in a manner that does not directly reveal the identities of the proposing team members of their institutions. This includes not only the main S/T/M section of the proposal, but also any other sections of the anonymized proposal document (e.g. the OSDMP, the table of personnel and work effort, and the redacted budget and budget justification). The requirements for proper anonymization are as follows:

- Do not claim ownership of past work or use possessive pronouns that indicate ownership. This especially applies to self-referencing. When discussing references and their contents in the text, use third person neutral wording. For example:

- Instead of statements like:

"Under my previously funded work [12], I modeled the shock propagation…" or

"As we have shown in our previous work [17], the inversion layer…” - Use statements like:

“Previous modeling studies of shock propagation [12] …” or

“It has been demonstrated in [17] that the inversion layer…”

- Instead of statements like:

- Do not use the proper names of people or institutions anywhere outside of the reference list in the anonymized proposal document. This includes, but is not limited to, page headers, footers, diagrams, figures, watermarks, or PDF bookmarks. The only exceptions to this prohibition are for named phenomena, objects, or general use facilities such as:

- The Van Allen Radiation Belts, Comet Hyakutake, Barnard’s Star, the NIST Atomic Spectra Database, the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes, etc.

- Do not associate proposal personnel with named teams or collaborations. This prohibition includes statements such as:

- “The PI is a member of the IceBridge Science Team.”

- “Co-I 1 chairs the steering committee of the NExSS Research Coordination Network.”

- Exceptions might be allowed in cases where the named collaboration is large and the role of the team member in the collaboration is not specified. However, when in doubt, contact the cognizant program officer for guidance.

- Do not include institutional logos or other identifying insignia anywhere in the anonymized proposal document.

- Do not use pronouns that indicate the sex of team members (e.g. he, she, his, her, etc.) anywhere in the anonymized proposal document.

- Reference callouts in the text must be written in numerical format, e.g. [1], with each number corresponding to the full citation in the reference list. It is recommended that callouts appear in numerical order in the text and that the reference list is presented in numerical order to simplify navigation between the proposal and the reference list for reviewers.

- Use of unpublished findings, exclusive access datasets, and or proprietary tools should be cited using language such "obtained in private communication" or "from private consultation". When using this type of citation, do not identify with whom the personal communication took place, i.e., do not refer to the names of individuals or provide a description of the associated team or group.

- Do not include statements designed exclusively to promote the general knowledge, experience, facilities, and past accomplishments of the proposing team or the characteristics and capabilities of the proposers or proposing institution(s), even in anonymized format. Such language is allowed only insofar as necessary to establish the team’s ability to execute the specific tasks proposed. This prohibition includes statements such as:

- “The proposing team has more than 50 combined years of experience and a successful record of funding under NASA, NSF, and DARPA programs…”

- “Over the past decade, the team has built a comprehensive laboratory that is fully complemented with the latest instrumentation and internationally recognized as the preeminent facility for research in the field of…”

- The PI institution has a proven track record of producing flight hardware for applications in more than a dozen NASA suborbital and suborbital-class missions.”

Validation of the qualifications and capabilities of the proposing team occurs after the review of the anonymous proposal and is explicitly excluded from consideration during the merit evaluation of the anonymized proposal. Inclusion of material touting the proposer’s credentials not only consumes space in the page-limited S/T/M section with information that is not salient to the merit evaluation but also undermines the spirit of the DAPR process.

A Note About the OSDMP

Unless otherwise stated in the program element, all ROSES proposals are required to include an “Open Science and Data Management Plan” (OSDMP) that describes how publications, data, and software resulting from the proposed investigation will be made publicly available. In most cases, the OSDMP is included as a separate 2-page section of the anonymized proposal document, outside of the Scientific/Technical/Management (S/T/M) section. However, there are some program elements that require the OSDMP to be included within the page-limited S/T/M section so proposers should be careful to follow the instructions in the program element to which they are proposing. For more information on the OSDMP please see Section II.C of the ROSES Summary of Solicitation and https://science.nasa.gov/researchers/sara/faqs/OSDMP.

Return without Review of Proposals with Egregious DAPR Errors

SMD understands that dual-anonymous peer review represents a major shift in the preparations and evaluation of proposals and, as such, there may be occasional minor errors in writing anonymized proposals. However, SMD reserves the right to return without review proposals with anonymization errors so pervasive and/or numerous that it is deemed impossible to fairly evaluate the proposal within the context of the dual-anonymous process.

SMD further acknowledges that some proposed work may be so specialized that, despite attempts to anonymize the proposal, the identities of the Principal Investigator and team members may be discernable. As long as the guidelines are followed, SMD will not return these proposals without review.

Common Pitfalls in the Preparation of Anonymized Proposals

Below is a non-exhaustive list of common pitfalls when preparing anonymized proposals. Proposers should be careful to avoid these common errors when preparing and submitting their proposals:

- Including metadata (e.g., PDF bookmarks, document properties) that reveal the name of the PI.

- Recycling proposals prepared prior to dual-anonymous peer review and not carefully anonymizing the text.

- Providing the names of organizations or investigators in the proposal summary, title page, table of contents, or in a header or footer.

- Use of pronouns that indicate the sex of proposal team members, especially in the summary of work effort and budget justification.

- Providing the origin of travel for professional travel (e.g., conferences).

- Mentioning the institution name in the Budget Narrative.

- Including the PI or Co-I names or institutional insignia in budget tables.

- Attempting to “redact” identifying information by inserting a black rectangle over parts of the text, versus formally redacting the text using specialized software.

- Including some or all of the content of the “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized” document within the main proposal PDF.

- Failing to remove all editorial comments and other markups entered during the drafting and revision of the proposal prior to its submission.

Many of these issues may be resolved by carefully searching the anonymized proposal document for identifying information, e.g., PI name, Co-I name(s), institution(s) before submission.

The “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized” Document

The other principal component of your DAPR proposal is the companion, “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized”, or simply E&R document. The E&R document contains the information necessary for a reviewer to validate that the qualifications of the proposing team and the resources to which they have access are suitable for conducting the proposed investigation.

In general, the "Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized" document will contain the following elements:

- A list of all team members, together with their institutional affiliations and roles (e.g., PI, Co-I, collaborator).

- Brief descriptions of the scientific and technical expertise each team member brings, emphasizing the experiences necessary to be successful in executing the proposed work.

- A brief discussion of the roles and responsibilities of each team member in the implementation of the proposed investigation.

- A discussion of specific resources (“Facilities and Equipment”, e.g., access to a laboratory, observatory, specific instrumentation, or specific samples or sites) that are required to perform the proposed investigation.

- A summary of work effort, to include the non-anonymized table of work effort. The table should be identical to that presented in the anonymized proposal document, but with the roles now also identified with names.

- Biographical sketches: use the new NASA grants policy format for biographical sketches (docx). See also the grants policy list of requirements for what to include here (PDF) and refer to the grants policy video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXraCMrhSeE.

- Statements of Current and Pending support: use the new grants policy format for current and pending support (docx). See also the grants policy list of requirements for what to include here (PDF) and refer to the grants policy video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qXraCMrhSeE.

- Letters of resource support, if required by the program element.

- Any other required content that might identify proposers, (e.g., demonstration of access to required facility) or other specialized documentation explicitly required by the program element.

Again, proposers should review the instructions provided in the program element to which they will propose to ensure that they are aware of any program-specific guidance/requirements for the contents and preparation of their E&R document.

Example Text for Anonymized Proposals

Much of the following text has been reproduced, with permission, from the Hubble Space Telescope dual-anonymous peer review website.

Here is an example of text from a sample proposal:

- Over the last five years, we have used infrared photometry from 2MASS to compile a census of nearby ultracool M and L dwarfs (Cruz et al, 2003; 2006). We have identified 87 L dwarfs in 80 systems with nominal distances less than 20 parsecs from the Sun. This is the first true L dwarf census a large-scale, volume-limited sample. Most distances are based on spectroscopic parallaxes, accurate to 20%, which is adequate for present purposes. Fifty systems already have high-resolution imaging, including our Cycle 9 and 13 snapshot programs, #8581 and #10143; nine are in binary or multiple systems, including six new discoveries. We propose to target the remaining sources via the current proposal.

Here is the same text, re-worked following the anonymizing guidelines:

- Over the last five years, 2MASS infrared photometry has been used to compile a census of nearby ultracool M and L dwarfs [6,7]. 87 L dwarfs in 80 systems have been identified with nominal distances less than 20 parsecs from the Sun. This is the first true L dwarf census a large-scale, volume-limited sample. Most distances are based on spectroscopic parallaxes, accurate to 20%, which is adequate for present purposes. Fifty systems already have high-resolution imaging available from two recent HST snapshot programs [REFERENCE]; nine are in binary or multiple systems, including six new discoveries. We propose to target the remaining sources via the current proposal.

Here is another example of text from a sample proposal:

- In Rogers et al. (2014), we concluded that the best explanation for the dynamics of the shockwave and the spectra from both the forward-shocked ISM and the reverse-shocked ejecta is that a Type Ia supernova exploded into a preexisting wind-blown cavity. This object is the only known example of such a phenomenon, and it thus provides a unique opportunity to illuminate the nature of Type Ia supernovae and the progenitors. If our model from Rogers et al. (2014) is correct, then the single-degenerate channel for SNe Ia production must exist. We propose here for a second epoch of observations which we will compare with our first epoch obtained in 2007 to measure the proper motion of the shock wave.

Here is the same text, again re-worked following the anonymizing guidelines:

- Prior work [12] concluded that the best explanation for the dynamics of the shockwave and the spectra from both the forward-shocked ISM and the reverse-shocked ejecta is that a Type Ia supernova exploded into a preexisting wind-blown cavity. This object is the only known example of such a phenomenon, and it thus provides a unique opportunity to illuminate the nature of Type Ia supernovae and the progenitors. If the model from [12] is correct, then the single-degenerate channel for SNe Ia production must exist. We propose here for a second epoch of observations which we will compare with a first epoch obtained in 2007 to measure the proper motion of the shock wave.

Here is a third example of text from a sample proposal:

- Before and after radiolysis, we will test changes in ice composition with our established cryogenic mass spectrometry technique (2S-LAI-MS) [Henderson and Gudipati 2014; Henderson and Gudipati 2015]. Our technique uses an IR laser tuned to the absorption wavelength for water to gently eject the sample into the gas phase, where it can be ionized by a UV laser and analyzed by time-of-flight mass spectrometry. A key advantage of our technique is that compositional information can be obtained directly in situ, for temperatures that are relevant to Europa (i.e., 50, 100, 150 K), without a need for warming to room temperature or other sample preparation. We will also perform continuous mass spectral analyses (using a residual gas analyzer and a quadrupole mass spectrometer already installed) during radiation to quantify the amount of sputtered material and evolved gas byproducts.

Here is the same text, again re-worked following the anonymizing guidelines:

- Before and after radiolysis, we will test changes in ice composition with an established cryogenic mass spectrometry technique [12,13]. This technique uses an IR laser tuned to the absorption wavelength for water to gently eject the sample into the gas phase, where it can be ionized by a UV laser and analyzed by time-of-flight mass spectrometry. A key advantage of this technique is that compositional information can be obtained directly in situ, for temperatures that are relevant to Europa (i.e., 50, 100, 150 K), without a need for warming to room temperature or other sample preparation. We will also perform continuous mass spectral analyses during radiation to quantify the amount of sputtered material and evolved gas byproducts.

Another common situation that occurs in proposals is when a team member has institutional access to unique facilities (e.g., access to a laboratory, observatory, specific instrumentation, or specific samples or sites) that are required to accomplish the proposed work. An anonymized proposal does not prohibit stating this fact in the Scientific/Technical/Management section of the proposal; however, the proposal must be written in a way that does not identify the team member. Here is an example:

- "The team has been awarded XX days of telescope time on Keck to observe Titan" or "The team has XX days at the NASA Ames Vertical Gun Range to study impacts on Titan" or "The team has XX days in the NASA Venus In-situ Investigations Chamber, which will enable us to examine the properties of sulfuric acid rain on Venus."

Note: in this situation, NASA strongly recommends that the team provide detailed supporting information (e.g., a letter of resource support) in the "Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized" document to validate the claim.

Assessment of Proposals in Dual-Anonymous Peer Review

As discussed above, the overarching objective of dual-anonymous peer review is to reduce the impact of cognitive bias in the evaluation of the merit of a proposal. To achieve this goal, reviewers are instructed to evaluate proposals based on their scientific merit, NASA relevance, and cost reasonableness without taking into account the identity of the proposers. Here are some specific instructions that are provided to reviewers:

- Evaluate proposals solely on the scientific/technical merit of the work proposed. Remember to discuss the science and not the people.

- Do not spend any time attempting to identify the PI or the team.

- In the panel discussions, do not speculate on identities, insinuate the likely identities, or instigate discussion on a possible team’s past work.

- When writing evaluations, use neutral language focused on the work and not the people (e.g. instead of saying, "what they propose to investigate" or "the team has previously evaluated similar data" say “the proposed project is designed to address” or “the proposal summarizes a previous evaluation involving similar data”).

In addition, if at any point a reviewer suspects they know the identities of the proposing team, they are instructed: (1) to inform the cognizant program officer of the situation; and (2) not to share their suspicions with their fellow reviewers. There are procedures in place for assessing and mitigating any such issues.

Each DAPR review panel is assigned a NASA Civil Servant to serve as a “leveler”. The leveler is present in the panel room throughout the discussion and rating of all proposals, but it is not their job to participate in the technical evaluation of proposals. Instead, they are present to serve as a facilitator and process monitor only. The leveler’s primary function is to ensure that the panel deliberations focus on the evaluation criteria that we provide, and do not stray into speculation about the identities of the proposers, their perceived attributes, or the quality of their past work. If a panel discussion does stray into conjecture about the identities of the proposers, it is the leveler’s responsibility to step in and redirect or refocus the discussion. Levelers even have the authority to stop the discussion of a proposal if their efforts to redirect the panel are unsuccessful.

Validation of the E&R Documents

As a final check, and only after the evaluation and rating of all the anonymized proposal documents assigned to the panel has been completed, panelists are provided with the E&R documents for only the subset of proposals that scored highly enough that they may reasonably be considered for selection. The fraction of the proposals that go through this validation process is determined by the cognizant program officer based on the distribution of ratings and the expected selection rate for the program. Based on this information, the panel assesses the qualifications of the team and the suitability of the facilities, equipment and other resources to which they have access for conducting the proposed investigation.

For most programs, the ability of a team to write a highly meritorious anonymized proposal provides strong evidence that they are well qualified to conduct the work that they proposed. Accordingly, the process of validating the associated E&R document involves simply confirming that the information it contains supports that expectation. After reviewing E&R document, the panel assigns it to one of the three following categories:

- Uniquely Qualified: The “Expertise and Resources” document demonstrates that the team is both exceptionally capable of executing the proposed work and has singular access to expertise or resources upon which the success of the investigation critically depends.

- Qualified: The team has appropriate and complete expertise to perform the work, and appropriate allocations of their time are included. Any facilities, equipment and other resources needed to execute the work are available.

- Not Qualified: The “Expertise and Resources” document demonstrates severe deficiencies in the necessary expertise and/or resources to execute the proposed investigation.

It is NASA’s expectation that the overwhelming majority of proposing teams will fall in the “Qualified” category. The assigned category of each team is recorded in a separate E&R Validation document. If the panel categorizes an E&R document as either “Uniquely Qualified” or “Unqualified”, they are required to provide a written statement justifying their categorization. Panels may or may not provide comments in support of a “Qualified” categorization.

Regardless of the results of the E&R Validation stage, panels are not permitted to modify the written panel evaluation or rating of a proposal from the first stage of the review.

A Variation on the E&R Assessment: E&R Evaluation

The process described above for validating the contents of the E&R documents constitutes the default approach that will be used by the vast majority of program elements. However, there may be some program elements for which the knowledge and expertise demonstrated by the team’s ability to write a highly meritorious proposal are not sufficient to establish the likelihood that a proposed investigation can be executed successfully. For example, this might be the case for programs that involve the development of flight hardware for suborbital or suborbital-class investigations. The success of such work depends not only on the expertise of the team, but also on the availability of highly specialized tools and facilities, and a level of institutional support that goes beyond that required for typical PI-led research grants. In these specialized cases, the Program Officer may adopt a more rigorous approach to the “Expertise and Resources” assessment phase of the review that is called E&R Evaluation.

E&R Evaluation follows the same general process as E&R Validation—it occurs only after the merit evaluation and rating of all the anonymized proposals is complete, it involves only the E&R documents of proposals that are likely to be considered for selection, and its outcome cannot affect the results of the merit evaluation stage of the review. However, under E&R Evaluation, the components of the E&R document are subject to a more structured and in-depth assessment than is the case for the standard E&R Validation approach.

In the rare cases where it is used, the intent to follow the alternative evaluation process for the “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized” documents will be clearly called out and described in the text of the associated program element along with the evaluation criteria that will be applied. Panels will capture written findings from their evaluation and based on those findings, assign the E&R documents to one of the following three categories:

- Exceeds Expectations: The qualifications of the team, the specialized tools and facilities to which they have access, and the capabilities of the proposing institution(s) significantly exceeds the level required for successful implementation of the proposed investigation. Any concerns voiced by the panel are minor in nature and unlikely to significantly impact the overall success of the investigation.

- Meets Expectations: The qualifications of the team, the specialized tools and facilities to which they have access, and the capabilities of the proposing institution(s) are likely sufficient to successfully implement the proposed investigation. Weaknesses identified by the reviewers may be substantive but are correctable and, subject to corrective action, there is a high likelihood that the investigation can be executed successfully.

- Does Not Meet Expectations: Taken as a whole, the qualifications of the team, the specialized tools and facilities to which they have access, and the capabilities of the proposing institution(s) are clearly not sufficient to successfully implement the proposed investigation. One or more weaknesses identified by the reviewers are substantial and, even with remedial action, there is a significant likelihood that proposed investigation will not be fully successful.

Unlike E&R Validation, NASA has no expectation regarding the distribution of proposals between these categories; the categorization should be consistent with the balance of strengths and weaknesses identified by the panel.

The findings and categorization of the E&R document are subsequently provided to the selecting official along with the written merit evaluation and rating of the anonymized proposal document and both are considered in making selection decisions. The written findings and categorization from the E&R Evaluation (if applicable) will be returned to proposers along with other documentation from the review of their proposal.

DAPR Contacts

Questions about specific program elements reviewed under DAPR should be sent to the point of contact in the summary table of key information at the bottom of the program element and posted on the program officer list. General questions regarding DAPR may be directed to Douglas Hudgins douglas.m.hudgins@nasa.gov and cc sara@nasa.gov.

Dual-Anonymous Peer Review Questions and Answers

Last updated February 2025

Q1. If I slip up in anonymizing my proposal, will it be returned without review?

A1. NASA understands that dual-anonymous peer review represents a major shift in the evaluation of proposals, and as such there may be occasional slips in writing anonymized proposals. However, NASA reserves the right to return without review proposals that are particularly egregious in terms of the identification of the proposing team.

NASA further acknowledges that some proposed work may be so specialized that, despite attempts to anonymize the proposal, the identities of the Principal Investigator and team members are readily discernable. As long as the guidelines are followed, NASA will not return these proposals without review.

Q2: How will you deal with conflict of interest and bias?

A2: The familiar proposal-level scientific ethics conflicts of interest (i.e. institutional, professional, personal conflicts) do not automatically apply to the review of anonymized proposals. Nevertheless, the NASA program scientist uses the institutional affiliations available from NSIRES to cross-check the names and institutions of proposing team members against those of the reviewers. In this way, they can take any (unrecognized) conflicts-of-interest into consideration during the construction of the review panels.

If at any point, a reviewer believes they have specific knowledge of the identities of the proposers—whether prior to the panel meeting or during the panel discussion of a proposal—they are instructed to contact the cognizant program officer to discuss the matter and not to discuss their suspicions with any other members of their review panel. The program scientist will assess any potential conflicts of interest that arise in this situation and take appropriate steps to mitigate them.

For reviewers that are Federal Civil Servants, it has been determined that Statutory conflict-of-interest regulations apply even in the context of an anonymous review. Consequently, civil-servants and IPAs must continue to self-certify against financial conflicts-of-interest and regulatory impartiality concerns. Accordingly, a listing of the identities of proposers and proposing organizations of all the proposals assigned to a panel are still made available to civil-servant reviewers for self-certification purposes, albeit without direct attribution to any specific proposal in the panel.

Q3: If the identity of the “proposing teams and institutions” is shrouded in secrecy, how then are proposing teams and institutions to discuss their track-record, ongoing work, complementary endeavors, institutional assets? For example, if an institution has been working closely with NASA for 40+ years on one specific topic (say, radar over ice), wouldn’t all the programmatic, institutional, and PI experience that goes with that be lost from the review process?

A3: The anonymized proposal has no prohibition on discussing these aspects, merely that they be discussed without attribution to a particular investigator or group. In situations such as this, NASA recommends writing “previous work” instead of “our previous work”; or using “obtained in private communication”. Proposers should be able to make their case through their description of their proposed program of observations and analysis that they have the necessary skills to achieve success; if specific skills are required, the panel will flag that and will be able to verify this when they consult the “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized” document. The panel will provide a full analysis of the “Expertise and Resources Not Anonymized” document and vote on using a three-point scale.

Q4: While it is not possible for the proposing teams not to show any information in the proposals that might reveal their identities, such as the context and motivation of the proposed research, unique methodologies, and cited references, why keep the reviewers guessing who the proposers are (leading to undesirable consequences)? Furthermore, the track records of the proposers should be part of the merits of the proposals.

A4: It is entirely appropriate that the context and motivation of the research be addressed, as well as unique methodologies, references, etc. The main difference is that these aspects should be discussed without attribution to a particular investigator or group in the main body of the proposal. Remember that the goal of dual-anonymous peer review is to not make it completely impossible to guess the identities of the investigators, but to shift the focus of the discussion away from the individuals and toward the proposed science.

Furthermore, although the overall merit of a DAPR proposal is assessed based only on the information provided in the anonymized proposal document, assessment of the qualifications, track record, and access to unique facilities is still an important component of the process—it is just that that assessment is separated out and occurs in the second stage of the review.

Q5: Assuming that the institution also has to be anonymous, how do reviewers determine if there are sufficient institutional resources to do the research?

A5: The track records of the proposing team will be addressed in the “Expertise and Resources – Not Anonymized” document and voted on using a three-point scale (uniquely qualified; qualified; not qualified).

Q6: What do you expect the unintended consequences of this action to be? Does this really serve the meritocracy?

A6: Our experience to date with DAPR is illustrated in the figure above showing the success rates of proposals from different classes of research institutions before and after the adoption of DAPR. The fact that the success rates of proposals from larger, more research-intensive institutions is not strongly affected by the introduction of DAPR indicates that there are few unintended consequences. However, in implementing and expanding the use of DAPR, NASA will ensure:

- Proposers are provided with clear and complete information and guidance for preparing and submitting their DAPR proposals;

- Review panels are properly instructed about the DAPR process and NASA’s expectations regarding the conduct of DAPR proposal reviews.

In addition, NASA will monitor and report the outcomes of our DAPR reviews on an ongoing basis to ensure that we are meeting the goal that all proposals submitted to NASA are reviewed in an objective and fair manner that reduces the impacts of any cognitive biases.

Q7: The DAPR Guidelines used say that an additional page was allotted for the Proposal Summary. But I don’t see that anymore, what happened?

A7: This is no longer needed since reviewers will now be able to see the summary from the NSPIRES cover page. So ensure that your summary on NSPIRES is anonymized! .

Q8: Is a table of contents permitted? I cannot find any mention of it in the DAPR guidance or in the text of B.4 HGIO.

A8: The Guidebook for proposers and the ROSES summary of solicitation set the default rules unless they are superseded by, e.g., B.1 The Heliophysics Research Program Overview or the program element. Since both the Guidebook for proposers and the ROSES summary of solicitation allow for a Table of Contents (of up to one page) this is permitted unless it is specifically prohibited. There is no mention of this in either B.1 or in B.4 Heliophysics Guest Investigators Open so it is permitted and it does not count against the page limited S/T/M section.

Q9: Even if the references are done by number [1, 2, etc.] and referencing is done in the 3rd person, there will be good number, maybe even dominant number, of references to my own prior work. So, it is very conceivable that a reviewer could guess by that who is proposing or at least from what group or institution the proposal comes.

A9: The objective of the dual-anonymous peer review (DAPR) is to minimize the impact of cognitive bias in the peer review process by eliminating “the team” as a topic of discussion during the scientific evaluation of a proposal. However, DAPR does not achieve this goal by making it somehow impossible for reviewers to figure out who the authors of a proposal might be (an unrealistic goal for the review of scientific proposals). Indeed, the effectiveness of DAPR doesn’t derive from maintaining absolute, iron-clad anonymity. Rather, the effectiveness of DAPR derives from the way proposals are written; a way that decouples the proposed investigation from the people and institutions who are conducting that investigation. In changing the way information is presented in a proposal, DAPR naturally creates a shift in the focus of the review, naturally drawing attention away from the perceived characteristics of the people and institutions involved and placing it squarely on the intrinsic scientific and technical merit, NASA relevance, and cost of the proposed investigation. To further reinforce this shift, reviewers are explicitly instructed not to engage in “detective work” in an effort to identify the proposing team members, and “levelers” are assigned to each panel to ensure that panel discussions do not stray into speculation about the identity of the proposing teams.

Q10: Could you provide more information on the content of the budget and justification in the anonymous proposal?

A10: First and foremost, proposers should understand that there has been no change in the requirement that all information pertaining to salary levels, benefits, and overhead rates be redacted from the budget and budget justification included in the main proposal document. This requirement is the same as it has been for the last several proposal cycles. Beyond this requirement, under the dual-anonymous peer review process, proposers should also take care to anonymize the budget and budget narrative in the main proposal document by removing any language, logos, etc. that would reveal the names and/or institutions of the members of the proposing team. Note that neither of these requirements–redaction and anonymization–apply to the “Total Budget” document, which is uploaded separately from the main proposal document and is not seen by the reviewers.

Q11: Should I anonymize the metadata in my proposal?

A11: Yes. Please ensure that metadata (e.g., PDF bookmarks) that could give information about the proposing team and/or institutions is redacted.